Mr. Gorenflo was with the Defense Innovation Unit-Experimental (DIUx) at the time of the NSL Symposium

Admiral, thanks so much. It’s great to be here with shipmates, shore mates, submariners, old friends, and to be able to discuss DIUX with you today. When Admiral Padgett, for whom I’ve had the privilege of working twice in my past, called and asked if I would be willing to come and speak at the Naval Submarine League annual symposium, you know what the right answer is. It’s yes, especially given his new role as Sean Connery’s body double.

You don’t want to disappoint him. Then as I was making my preparations to come here and sitting through some of the other presentations this morning, it became clear that I’m kind of the pinch hitter in the wrong uniform, amidst all the other folks who are doing presentations.

To continue in the theme of constructive disappointment constructive dissatisfaction I certainly had some of those feelings as I was packing for this trip and came to the realization that I could not appear here in my standard Silicon Valley uniform of jeans and polo shirt. When I broke out the suits and dress shirts that I had put away in mothballs when I put the Pentagon in my rearview mirror, I found that they had about as much margin as the Ohio Replacement Program Schedule.

So with that in mind, I’m going to run you through the thesis behind DIUX, give you some of what we’ve achieved to date, why we’re doing it, how we’re doing it. I hope to do that and get us back on schedule. My slides are not as dense as some of our other slides we’ve seen today.

While the slide is coming up this is a great segue for why technology is a great thing to integrate into our military.

I’ve been promised flying cars and good collaboration tools. Here we go. Basically the thesis that Secretary Carter had when he wanted to start up the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental in Silicon Valley is fairly straight forward and one that submariners would understand.

That is, for the United States military to maintain its qualitative superiority over adversaries, actual and potential, we need to tap into all sources of technological superiority and innovation that are available in the United States.

For many years almost all of those sources were available inside what you could consider the cone of silence of the Department of Defense: the RDT&E enterprise, the engineering centers and laboratories, our colleagues in the defense industrial base, and the universities that we work with. The money that was spent there produced great results for the United States.

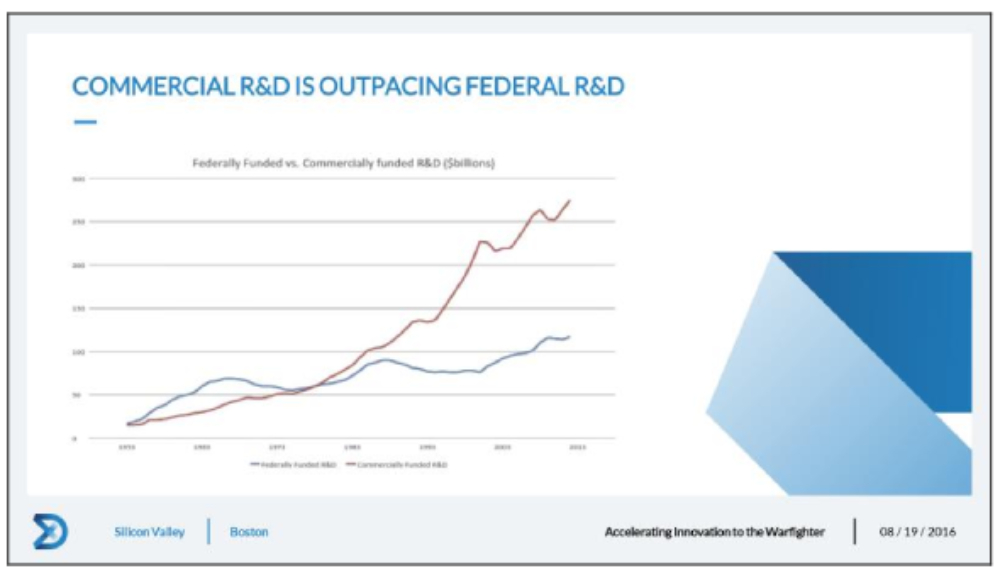

If you used R&D spending as a proxy and it’s not a perfect proxy but it’s a good and interesting proxy for innovation and technological development you can see that innovation was led by the Department of Defense through the first half of the Cold War. Then you see that R&D spending by corporations starts to exceed the trend line that’s available for the Department of Defense.

Now some of that is where the Department of Defense is a victim of its own success. There are technologies that we created inside the DOD, like the Internet and GPS and space technologies, that were transferred to the private sector and became great sources of economic value, which private companies were able to make great profits off of, create huge businesses, employ a lot of people, and deliver great capabilities to average citizens. All those are great things, which we should not begrudge at all.

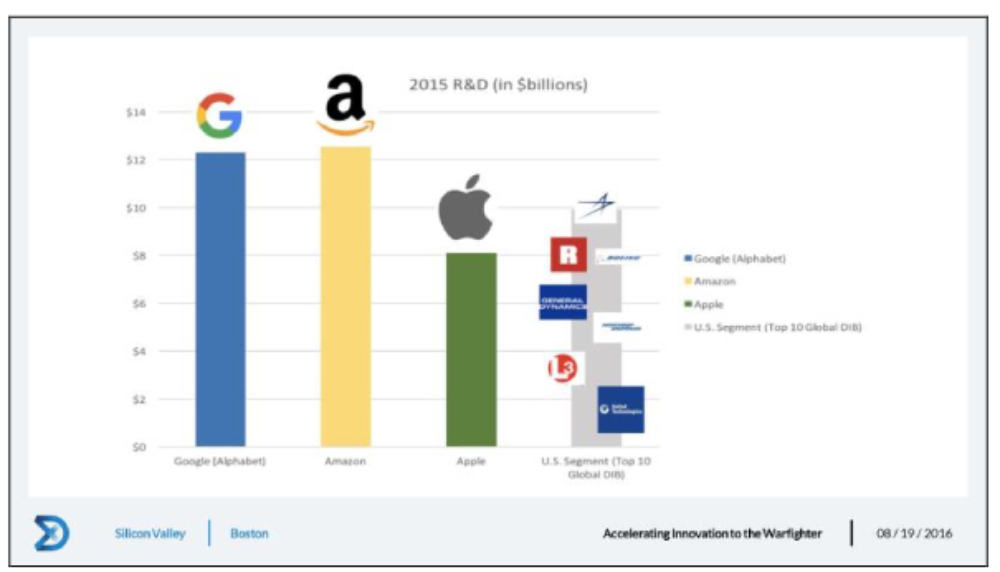

But when Secretary Carter saw these trends, and he did see them in the interregnum between his tenure as DEPSECDEF and SECDEF when he was a fellow at the Hoover Institution in Silicon Valley, he wanted to get another tool in the DOD’s toolkit to be able to tap into this source of innovation, and to take advantage of the investments the private sector had made, and bring those investments back. Go to the next slide. This is illustrative of how some of the huge high technology firms that you find in Silicon Valley these are public companies do their R&D spending.

Despite the fact that Apple is up there, this is not an apple to apple comparison. If you were to dig down into these numbers you would find that they’re not exactly comparable. But they’re illustrative of the amount of money that high technology firms in Silicon Valley are willing to spend to create products and services at the cutting edge of technology that give them a competitive advantage and deliver great experiences and services and products to their customers around the world.

So how do we leverage this surfeit of investment? If you look at it, there’s about a $200 billion delta between what private industry spends on R&D and what the federal government does. About $58 billion of that is in venture capital. More than half of that venture capital is employed in Silicon Valley.

So with that as the prologue, that’s why Secretary Carter established DIUX. He announced it in April of 2015 at the Drell lecture at Stanford University. The first employee showed up in August of 2015. I got there in October. We did kind of a reboot in May of this year and we’ve been kind of building the airplane as we’re flying it and pushing as hard as we can ever since we stood up the organization.

So what is our mission and how do we do it? If you’d go to the next slide? Basically our tasking from Secretary Carter is in Silicon Valley you do these four things.

First of all, we need to find ways to move at the speed of business. One of the things that we found in Silicon Valley when we started off there originally or just meeting people and chatting with them, is that there was a great reluctance to do business with the Department of Defense because we can be a tough customer to work with, not because we’re demanding but because many of our processes take an extraordinary amount of time.

If you’re a startup firm or a high tech company, where your product life cycles are six months and the half life of your technology is six months, you can’t afford to wait a year or year and a half for your government interlocutor to decide to make a decision, and then another year or year and a half where your government interlocutor to actually make a decision and deploy capital, when you can go to a venture capital firm on Sand Hill Road, get the money that you need and go to market with your product. So we had to find a way to move at a speed that’s at least sort of the same order of magnitude of what the folks in Silicon Valley are familiar with.

The second is we have to kind of allow some orthogonal thinking to go along. What do I mean by that? I guess the best example I can give of that is when we deal with our customers from the Department of Defense who want to come and work with us, we ask them to tell us what problem are you trying to solve. Don’t come to us with a requirements document. Come to us with, what’s the use case and what problem are you trying to solve.

There could be many different ways of attacking that problem that you haven’t thought of, but that folks here in Silicon Valley when I say here, where we work in Silicon Valley and the other places where DIUX is located have already solved that problem from a different vector that for whatever reason you just weren’t exposed to.

The third thing is we have to develop and maintain the right relationship with academia, with venture capitalists, with the established public high tech companies, and with the start up firms who have products that are ready to go to market. And we need to be able to and this has been talked about before here in the symposium we need to be willing to experiment and fail and learn from those failures and move on with that learning to try and serve our customers more effectively in the future.

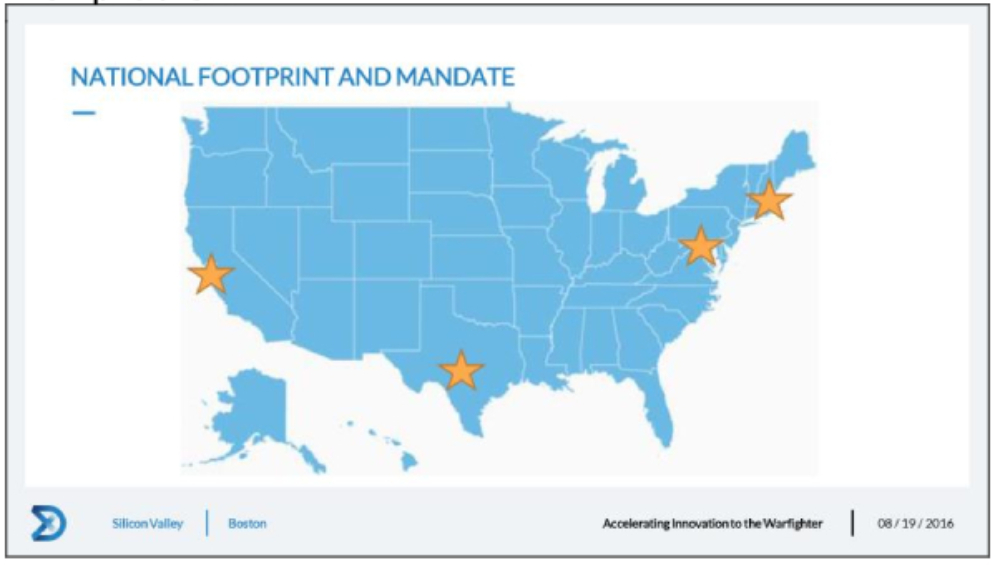

So we started in Silicon Valley. We established we also have an office in the Pentagon, because there’s a lot of interest in what’s going on at DIUX. We need folks at the Pentagon to help us engage with our stakeholders inside the Department of Defense, as well as on Capitol Hill and in the White House.

We established an office in Boston and we established a presence in Austin. The center of gravity of the number of people is in Silicon Valley. There’s probably going to be about between five and 10 in Boston, probably between three and four in Washington, D.C., and the Austin presence now is two folks. We’re trying to look at a model which leverages the reserve assets that are available in the Austin area to try and improve our presence there.

This is not to say that there aren’t other great innovation ecosystems in the United States. There are plenty of them. We have heard from the governors and mayors and congressmen and senators and folks who want us to establish presences elsewhere. I think that will be dependent on how successful we are in our mission to date and how we can leverage the assets that we have available to deliver for the war fighter, which is our primary focus.

So what are the arrows that we have in the quiver and how do we go about doing our mission? First of all, we’re looking to work with interested customers inside the Department of Defense. There isn’t a ‘one to n’ list of integrated priorities that we get from anybody. There isn’t a vetted process of problems to solve that we get from the Pentagon. But we do have direction from the SECDEF and the DEPSECDEF on areas that they want us to focus on, broad technology areas, and we do have folks who come to us with problems to solve that they haven’t been able to get solutions that they’re happy with elsewhere.

We work with them using the teams that we have in the organization. It’s principally uniformed military folks. Those folks come from both the active component and the reserve component and the National Guard and Air National Guard. We have government civilians and we have contractors, including folks who bring expertise as entrepreneurs and business leaders who can help us work our way through problems.

We have a commercial solutions opening contract vehicle. That’s a fancy name or a different name for a contract vehicle that uses other transaction authorities, which are available throughout the Department of Defense. It wasn’t created specifically for DIUX. We’ve just leveraged it for our particular needs. And we have co-investment funds. We got $20 million in RDT&E in FY ‘16. The president’s budget ‘17 has $30 million, subject to negotiation, of course, and approval by our partners on Capitol Hill in the authorization and appropriations committees.

We got all of these put together in May when the organization was rebooted by Secretary Carter to give us the tools that were needed to achieve the results that he wanted to achieve with establishing the organization.

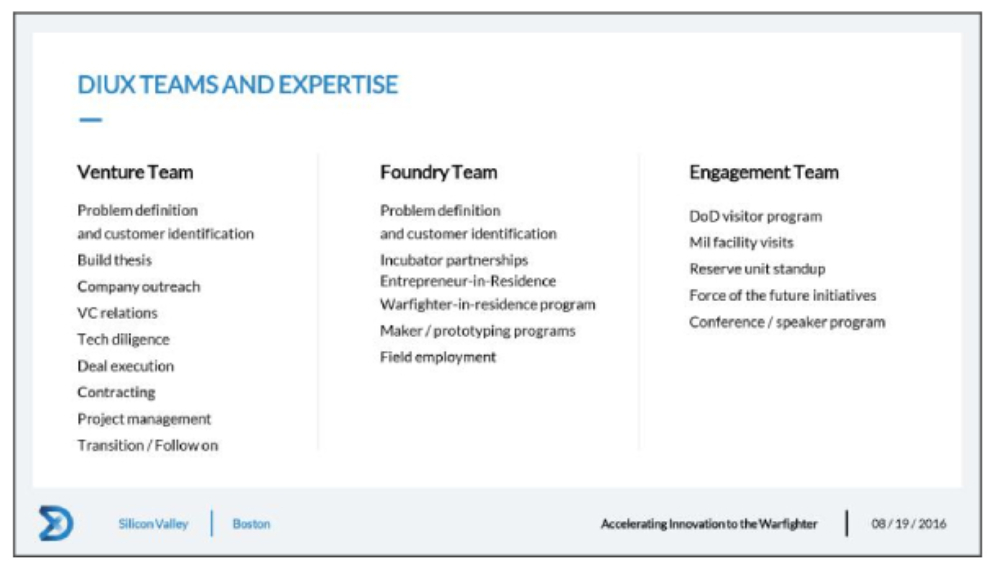

You could call these levels of effort or lines of effort or teams, whichever you prefer. The distinction is a little bit artificial, but we do have kind of three ways that we go about doing what we do. The first is kind of a venture team with a venture line of effort where we work with DOD customers. We try and understand what problem they’re trying to solve. We do market research to see what potential solutions there are out there, what companies are working on that and what’s the maturity of both the companies and their solutions.

We work with venture capitalists as well. We do due diligence on the technology that they are presenting to us. Then we work through advertising the problem on our web site, getting solution briefs in from companies who have technologies that could possibly solve the problem.

We do this in partnership, so we’re not a contracting organization ourselves. We do this in partnership with the Army Contracting Command in New Jersey, which are the pros from Dover, actually the pros from Picatinny, and have the other transaction authority contract vehicle. They have agreement officers on site with us that work with us to work through the other transactional authority contracting process.

We evaluate the solution briefs that are submitted. The briefs are very simple. They could be a five page white paper or a 15 slide slide deck. Based on those, we typically ask the companies whose solutions seem the most promising to give an in person presentation. They give a presentation either in-person or via Skype or some other type of collaboration software tool.

Then we negotiate agreements with those companies whose solutions seem most appropriate for the problem that has been given to us by the customer. Our internal goals are, from the closing of the commercial solutions opening problem statement, to when we identified companies and solutions of interest, is 30 days. From the beginning of the negotiations with those companies to the signing of an agreement, is another 30 days. We’ve done it as quickly as 31 days. Our average is between 50 and 60 days for those two parts of the process.

The foundry team or the foundry effort is for those problems for which there isn’t necessarily an existing kind of off the shelf or more or less existing technology solution that’s out there. Maybe it’s something where we have to kluge together two or more kinds of technologies to try and figure it out. But it’s an active prototyping opportunity and skill set and capability that we bring to our customers to help them work through what the solution would look like. It’s also an opportunity for a war fighter in residence to get paired with an entrepreneur in residence to work on this project. Those are two entities that we’re trying to bring together.

And then finally we’ve got a big engagement effort that’s going on. As you can imagine, echoing what Admiral Tofalo said, what the Secretary of Defense finds interesting, all the people that work with him find fascinating. So we’ve had any number of people who have noticed that the secretary has been out to visit Silicon Valley probably four or five times. So they figure, kind of like how the CNO during World War II came back from a meeting with General Marshal and said, I don’t know what this logistics is but I want more of it.

We’ve got a lot of folks in the Department of Defense who say, I’m not quite sure what this innovation in Silicon Valley is, but I want more of it, and I’m going to go visit. So we’ve had a lot of interest in coming out and arranging visits. We’re trying to figure out a way to do that that is useful for our DOD stakeholders and doesn’t take up unnecessarily time and bandwidth of the folks in Silicon Valley who are proud Americans and patriotic. But they have businesses to run, and endless meetings with no prospect of that turning into a business relationship just so they can explain how they do innovation, is not something that they want to continue to do without an end point in sight.

So we’re looking for ways to kind of regularize that engagement and make it useful for both parties. But also so the folks in Silicon Valley can get a better sense, in return, of what are the problems that leaders in the DOD are trying to work on. So if they have technologies or portfolio companies or other assets, maybe that would be something that they could vector towards trying to work on those particular problems.

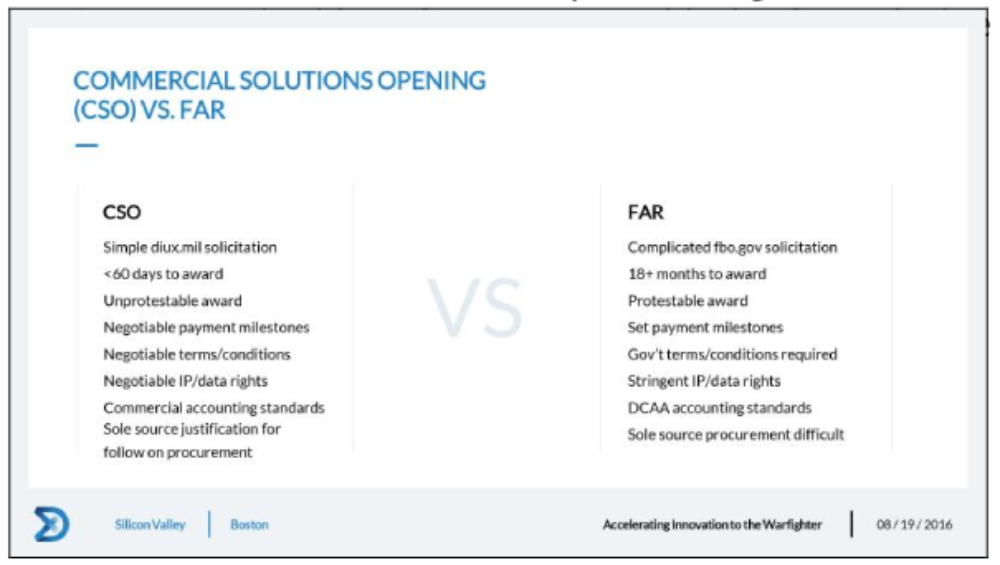

This is the quick slide which gives the delta between the commercial solutions opening other transaction authority contract and a typical FAR based contract. It’s a much simpler solicitation. Our internal goal is less than 60 days to award. The award itself is unprotestable.

What we ask when you come to us is that you bring the following to the table: First of all, commitment, that it’s a problem that you really want solved; dedicated personnel to be from your customer side, a program manager or project manager; and we ask for a co investment on the commercial solutions opening contracting effort. Typically it’s gone anywhere from 50-50, in other words DIUX puts in 50 percent and the customer puts in 50 percent, to where the customer puts in significantly more than we do.

By the way, any color of money can work with the CSO. It just depends on what the CSO is being used to procure. The vast majority of awards that we’ve given to date have been using RDT&E funds.

We just released our first quarterly report where we executed I’m going to have to use my reading glasses here to make sure I get the data correct, because I wouldn’t want to quote incorrect numbers. Between the time when we got the money and a contracting vehicle in May to the end of the fiscal year, we’ve put $36 million on award, $8.3 million of that was from DIUX and

$28 million was from the customers we were working with. The projects included a couple of cyber security software instantiations which are going to be tried out in various DOD networks. One is an endpoint security solution, another is a virtual machine security solution. And that basically exhausts my knowledge of how these things work, so you can ask me more questions on those, and I’ll try and answer them.

We also worked with a company to get a high speed drone that kind of supports some prototyping efforts on having drones work with fourth and fifth generation tactical aircraft. We have also an unmanned maritime surface vehicle. It’s basically a small sail and solar powered drone. The damn thing is pretty much indestructible and can provide a long-term fairly low profile presence on oceans around the world. This thing can gather all kinds of data, especially oceanographic and bathometric data.

We’ve contracted with a company to get an autonomous indoor tactical drone which could be used by special forces to go and map the insides of buildings before they go and try and get inside them. And we have a network change detection and processing software instantiation. Basically it is for the Internet of Things what Google is for the Internet of web sites. And again, that exhausts my level of knowledge of this cyber security thing, but feel free to ask.

So that’s my story and I’m sticking with it. I wanted to get us back on time and leave more time for questions. I’m happy to answer any questions you might have on what we’re doing, how we’re doing it, and with whom we are doing it. Thank you for the opportunity to speak to you today.