The following is an excerpt from Congressional Research Service

Report RL32665 dated May 15, 2017.

Navy’s New 355 Ship Ship Force Structure Goal

Introduction

On December 15, 2016, the Navy released a new force structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers.

The 355 ship force level goal is the result of a new Force Structure Assessment (FSA) conducted by the Navy. An FSA is an analysis in which the Navy solicits inputs from U.S. regional combatant commanders (CCDRs) regarding the types and amounts of Navy capabilities that CCDRs deem necessary for implementing the Navy’s portion of the national military strategy, and then translates those CCDR inputs into required numbers of ships, using current and projected Navy ship types.1 The analysis takes into account Navy capabilities for both warfighting and day to day forward deployed presence. The Navy conducts an FSA every few years, as circumstances require, to determine its force structure goal.

The new 355 ship force level goal replaces a 308-ship force level goal that the Navy released in March 2015. The 355-ship force level goal is the largest force level goal that the Navy has released since a 375-ship force level goal that was in place in 2002-2004. In the years between that 375 ship goal and the new 355-ship goal, Navy force level goals were generally in the low 300s (see Appendix B). The actual size of the Navy in recent years has generally been between 270 and 290 ships.

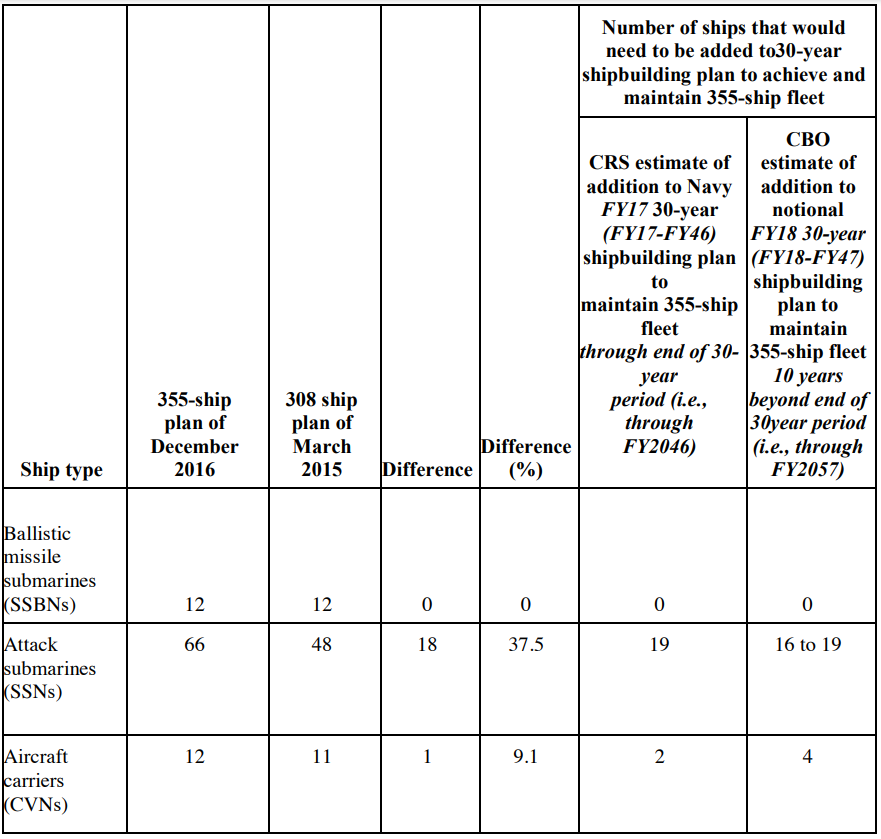

Table 1 compares the Navy’s new 355-ship force level goal to its previous 308-ship force level goal. As can be seen in the table, compared to the previous 308-ship force level goal, the new 355- ship force level goal includes 47 additional ships, or about 15% more ships, including 18 attack submarines, 1 aircraft carrier, 16 large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers), 4 amphibious ships, 3 combat logistics force (i.e., resupply) ships, 3 expeditionary support base ships (or ESBs these were previously called Afloat Forward Staging Bases, or AFSBs), and 2 command and support ships. The 34 additional attack submarines and large surface combatants account for about 72% of the 47 additional ships.

Table 1. New 355-Ship Plan Compared to Previous 308-Ship Plan

Source: Table prepared by CRS based on Navy’s FY2017 shipbuilding plan and information provided by CBO to CRS on April 26, 2017. The CRS and CBO estimates shown in the final two columns assume no service life extensions of existing Navy ships and no reactivations of retired Navy ships.

Notes: EPFs were previously called Joint High Speed Vessels (JHSVs). ESBs were previously called Afloat Forward Staging Base ships (AFSBs). The figures for additional small surface combatants shown in the final two columns are the net results of adding 12 small surface combatants in the earlier years of the 30 year plan and removing 4 or 2 small surface combatants, respectively, from the later years of the 30-year plan.

Apparent Reasons for Increasing Force-Level Goal from 308 Ships

The roughly 15% increase in the new 355-ship plan over the previous 308-ship plan can be viewed as a Navy response to, among other things, China’s continuing naval modernization effort;2 resurgent Russian naval activity, particularly in the Mediterranean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean;3 and challenges that the Navy has sometimes faced, given the current total number of ships in the Navy, in meeting requests from the various regional U.S. combatant commanders for day to day in region presence of forward deployed Navy ships.4 To help meet requests for forward deployed Navy ships, Navy officials in recent years have sometimes extended deployments of ships beyond (sometimes well beyond) the standard length of seven months, leading to concerns about the burden being placed on Navy ship crews and wear and tear on Navy ships.5 Navy officials have testified that fully satisfying requests from regional U.S. military commanders for forward-deployed Navy ships would require a fleet of substantially more than 308 ships. For example, Navy officials testified in March 2014 that fully meeting such requests would require a Navy of 450 ships.6

In releasing its 355-ship plan on December 15, 2016, the Navy stated that Since the last full FSA was conducted in 2012, and updated in 2014, the global security environment changed significantly, with our potential adversaries developing capabilities that challenge our traditional military strengths and erode our technological advantage. Within this new security environment, defense planning guidance directed that the capacity and capability of the Joint Force must be sufficient to defeat one adversary while denying the objectives of a second adversary.7

Compared to Trump Campaign Organization Goal of 350 Ships

The figure of 355 ships appears close to an objective of building toward a fleet of 350 ships that was announced by the Trump campaign organization during the 2016 presidential election campaign.

The 355-ship goal, however, reflects the national military strategy that was in place in 2016 (i.e., the Obama Administration’s national military strategy). A January 27, 2017, national security presidential memorandum on rebuilding the U.S. Armed Forces signed by President Trump states: “Upon transmission of a new National Security Strategy to Congress, the Secretary [of Defense] shall produce a National Defense Strategy (NDS). The goal of the NDS shall be to give the President and the Secretary maximum strategic flexibility and to determine the force structure necessary to meet requirements.”8

The Trump campaign organization’s vision for national defense comprised eight elements, one of which was to “Rebuild the U.S. Navy toward a goal of 350 ships, as the bipartisan National Defense Panel has recommended.”9 The Trump campaign organization did not delineate the composition of its 350-ship fleet.

The figure of 350 ships appeared to be a rounded-off version of a recommendation for a fleet of up to (and possibly more than) 346 ships that was included in the 2014 report of the National Defense Panel (NDP), a panel that provided an independent review of DOD’s report on its 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR).10

Four years before that, a fleet of 346 ships was recommended in the 2010 report of the independent panel that reviewed DOD’s report on its 2010 QDR. The 2010 independent panel report further specified that the figure of 346 ships included 11 aircraft carriers, 55 attack submarines (SSNs), and 4 guided missile submarines (SSGNs).11

Seventeen years earlier, a fleet of 346 ships was recommended in DOD’s 1993 report on its Bottom-Up Review (BUR), a major review of U.S. defense strategy, plans, and programs that was prompted by the end of the Cold War.12 The 2014 NDP report cited above referred explicitly to the BUR in making its recommendation for future fleet size:

We believe the fleet-size requirement to be somewhere between the 2012 Future Year Defense Program (FYDP) goal of 323 ships and the 346 ships enumerated in the [1993] BUR, depending on the desired “high low mix [of ships],”13 and an even larger fleet may be necessary if the risk of conflict in the Western Pacific increases.14

Additional Shipbuilding Needed to Achieve and Maintain 355 Ship Fleet

CRS and CBO Estimates

Although the 355-ship plan includes 47 more ships than the previous 308-ship plan, as shown in the final two columns of Table 1, more than 47 ships would need to be added to the Navy’s 30year shipbuilding plan to achieve and maintain the Navy’s 355- ship fleet, unless the Navy extends the service lives of existing ships beyond currently planned figures and/or reactivates recently retired ships.

This is because the FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan does not include enough ships to fully populate all elements of the 308-ship fleet across the entire 30-year period, and because some ships that will retire over the 30-year period that would not need to be replaced to maintain the 308-ship fleet would need to be replaced to maintain the 355-ship fleet. As shown in the final two columns of Table 1:

• CRS estimates that 57 to 67 ships would need to be added to the Navy’s FY2017 30-year (FY2017-FY2046) ship-building plan to achieve the Navy’s 355-ship fleet and maintain it through the end of the 30-year period (i.e., through FY2046).

• The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that 73 to 77 ships would need to be added to the Navy’s FY2018 30-year (FY2018-FY2047) shipbuilding plan to achieve the Navy’s 355 ship fleet and maintain it not only through the end of the 30-year period (i.e., through FY2047), but another 10 years beyond the end of the 30-year period (i.e., through FY2057).15

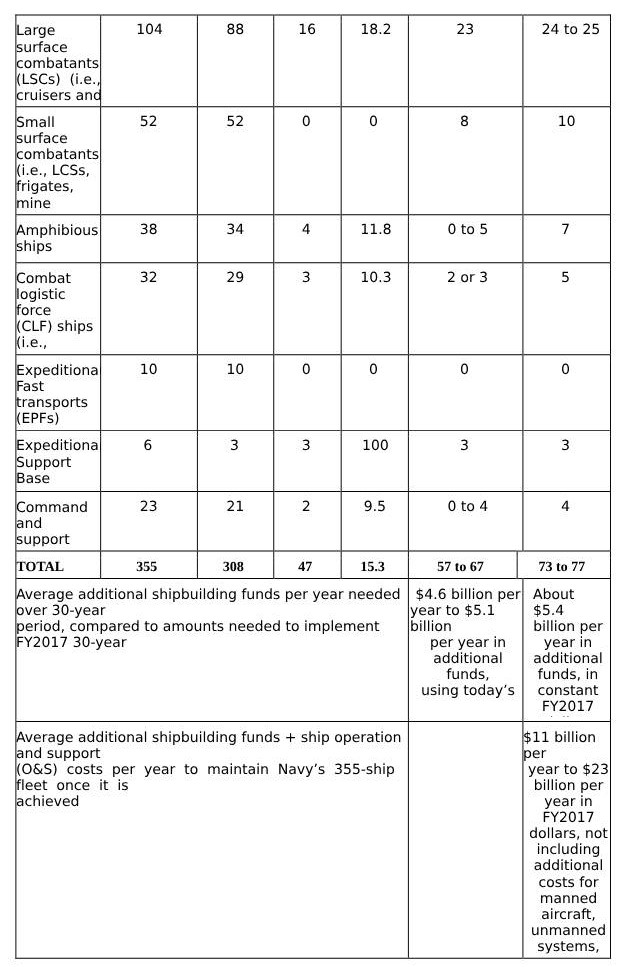

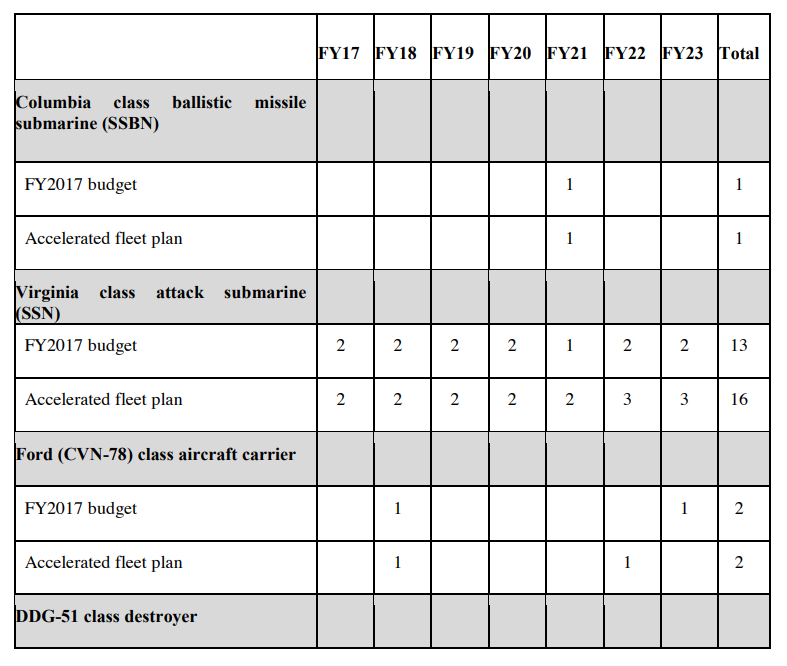

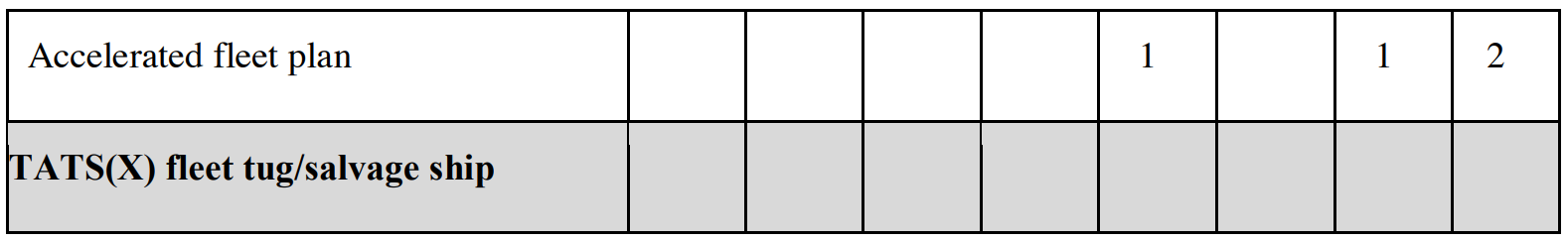

Navy February 2017 White Paper on Notional FY2017- FY2023 Shipbuilding and Aircraft Procurement Increases

A February 2017 Navy white paper entitled “United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan” sets forth “a path to expeditiously build capacity and improve lethality of the fleet” as “a first step towards a framework to develop strategic guidance and identify the investments needed to reinvigorate our naval forces.”16 The cover memorandum to the white paper states that the white paper addresses the following question: “How rapidly could the Navy increase its force size guided by operational requirements, industrial base capacity, and good stewardship of the taxpayers’ money?” The results of the analysis, the cover memo states, “could be considered as a ‘bounding case’ for a future plan to recover from a long period of deficit [i.e., less than optimal] investment.” The white paper presents notional increases in shipbuilding and aircraft procurement for the seven-year period FY2017-FY2023. Table 2 shows those notional increases.

Table 2. Navy Notional Accelerated Fleet Plan: Shipbuilding and Aircraft Procurement

From February 2017 Navy white paper

Source: United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, p. 4, with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

The white paper states that these notional increases are the maximum number of additional ships and aircraft that the Navy could purchase over the next seven years to get to required fleets levels as quickly as possible, relative to the current budget plan…. The Navy’s accelerated plan… sets the Navy on a path that is achievable with low levels of technical risk, reduces future costs, and provides capabilities that the Navy is highly confident will remain relevant over time.”17

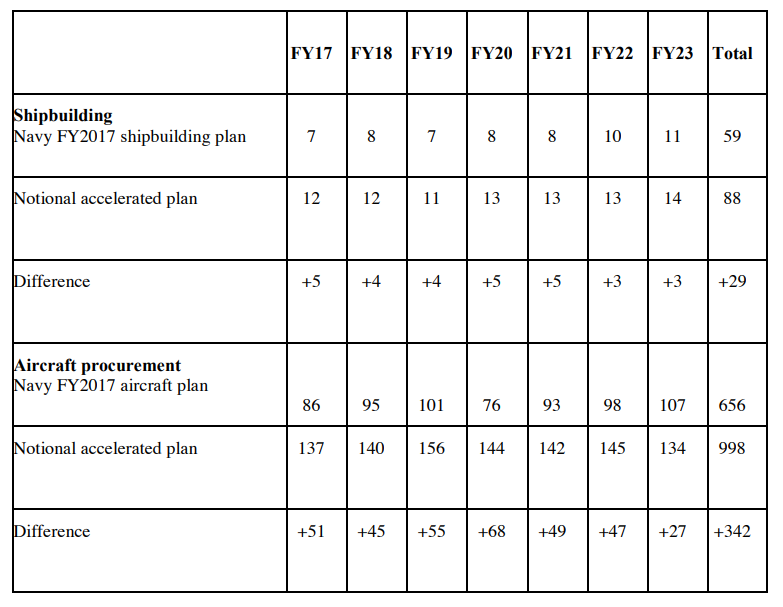

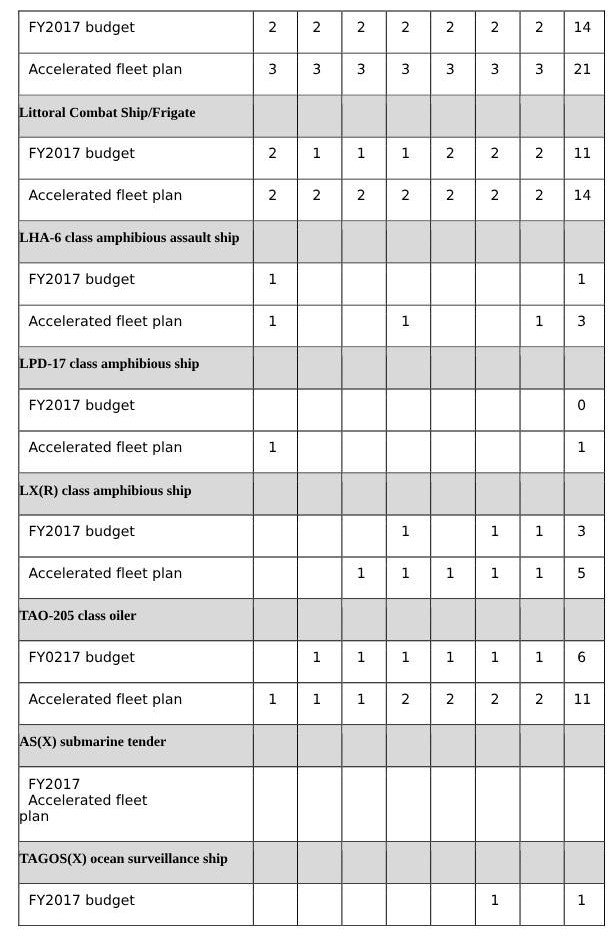

Table 3 shows, by individual program, the additional shipbuilding summarized in Table 2. As can be seen in Table 3, compared to the Navy’s FY2017 budget submission, the Navy’s notional accelerated fleet plan includes the following additional ships, among others, during the seven year period FY2017-FY2013:

• 3 Virginia-class attack submarines (SSNs);

• 7 DDG-51 class destroyers;

• 3 Littoral Combat Ships/frigates (LCSs/FFs);

• 2 LHA-6 class amphibious assault ships;

• 2 LX(R) class amphibious ships;

• 5 TAO-205 class oilers; and

• 3 TESB expeditionary support base ships.

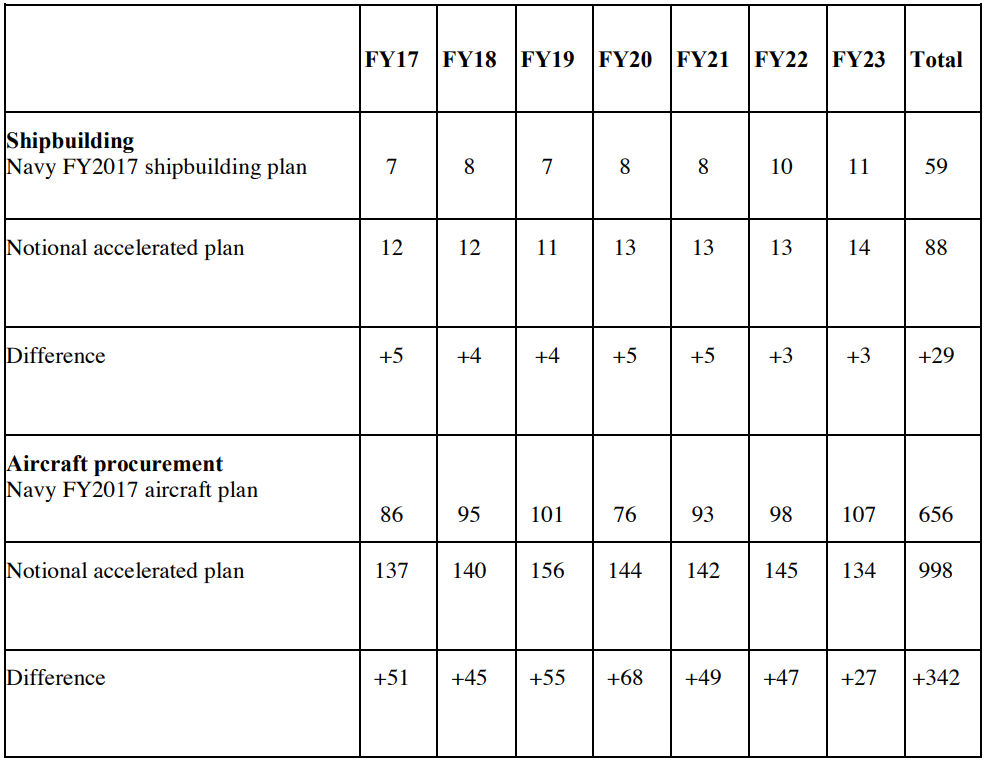

Table 3. Navy Notional Accelerated Fleet Plan: Shipbuilding by Program

From February 2017 Navy white paper

Source: United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, pp. 7-8, with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

As can be seen in Table 3, compared to the Navy’s FY2017 budget submission, the Navy’s notional accelerated fleet plan does not include additional aircraft carriers in the seven-year period FY2017-FY2023, but it accelerates the procurement of a carrier from FY2023 to FY2022. The Navy’s white paper states that under the accelerated fleet plan, procurement of carriers would be accelerated to a rate of one ship every 3½ years (i.e., a combination of three- and four year intervals) until a steady-state force of 12 carriers is achieved, and that the Navy would contract for carriers with two-ship multiyear contracts, starting with CVNs 80 and 81, the carriers that would be procured in FY2018 and FY2022.18

Time Needed to Achieve 355-Ship Fleet

Even with increased shipbuilding rates, achieving certain parts of the 355-ship force-level goal could take many years. For example, the 355-ship force level goal includes a goal of 12 aircraft carriers. Increasing aircraft carrier procurement from the current rate of one ship every five years to one ship every three years would achieve a 12-carrier force on a sustained basis by about 2030. As another example, the 355-ship force level includes a goal of 66 attack submarines. Increasing attack submarine procurement to a rate of three attack submarines (or two attack submarines and one ballistic missile submarine) per year could achieve a 65-boat SSN force by the late 2030s. CBO estimates that the earliest the Navy could achieve the 355-ship fleet would be 2035.19

Cost to Achieve and Maintain 355-Ship Fleet Shipbuilding Costs

Procuring the additional ships needed to achieve and maintain the Navy’s 355-ship fleet would require several billion dollars per year in additional shipbuilding funds. As shown in Table 1:

• CRS estimates that procuring the 57 to 67 ships that would need to be added to the Navy’s FY2017 30-year shipbuilding plan to achieve the Navy’s 355-ship fleet and maintain it through FY2046 would notionally cost an average of roughly $4.6 billion to $5.1 billion per year in additional shipbuilding funds over the 30-year period, using today’s shipbuilding costs.

• CBO estimates that procuring the 73 to 77 ships that would need to be added to the Navy’s FY2018 30-year shipbuilding plan to achieve the Navy’s 355-ship fleet and maintain it through FY2057 would cost, in constant FY2017 dollars, an average of $5.4 billion per year in additional shipbuilding funds over the 30-year period.20

The Navy’s February 2017 white paper on its notional accel- erated fleet plan states that, compared to the Navy’s FY2017 budget submission (whose five-year budget period covers the years FY2017-FY2021), the 23 additional ships shown in the first five years (FY2017-FY2021) of the seven year period presented in Table 2 would require about $32.2 billion in then-year dollars in additional funding, or an average of about $6.4 billion per year in then-year dollars.21

Aircraft Procurement Costs

CBO estimates that procuring the additional ship-based aircraft associated with the Navy’s 355 ship force level goal including an additional carrier air wing for an aircraft carrier, plus additional aircraft (mostly helicopters) for surface combatants and amphibious ships would require about $15 billion in additional funding for aircraft procurement.22

The Navy’s February 2017 white paper on its notional accelerated fleet plan states that, compared to the Navy’s FY2017 budget submission (whose five year budget period covers the years FY2017-FY2021), the additional 268 additional aircraft shown in the first five years (FY2017-FY2021) of the seven-year period presented in Table 2 would require about $29.6 billion in then year dollars in additional funding, or an average of about $5.9 billion per year in then-year dollars.23

Shipbuilding and Aircraft Procurement Costs

A March 22, 2017, press report stated:

The Navy needs potentially as much as $150 billion over current budget plans to “jumpstart” shipbuilding and get on a trajectory for a 355-ship fleet, the vice chief of naval operations said on Wednesday.

The money would add about 30 ships to the fleet beyond current plans, Adm. Bill Moran said.

The exact size of the future fleet doesn’t matter right now, but rather the Navy just needs to start boosting its investment in shipbuilding quickly which means buying many more Virginia class attack submarines, Arleigh Burke class destroyers and Ford class aircraft carriers in the next few years, he said.

“I’m not here to argue that 355 or 350 is the right number. I’m here to argue that we need to get on that trajectory as fast as we can. And as time goes on you start to figure out whether that number is still valid 10 years from now, 20 years from now 355 may not be the number,” Moran said today at the annual McAleese/Credit Suisse “Defense Programs” event.

“Our number, give or take, to get to 355, or just to get started in the first seven years, is $150 billion. That’s a lot of money.”

Moran told USNI News following his remarks that dollar figure wasn’t exact but was based on the Navy’s best guess for how much it would cost to immediately begin a fleet buildup. A Navy official told USNI News later that one internal Navy estimate put the cost at about

$80 billion over the seven years….

“When you look at the number that started our 355 trajectory, to jump start it in order to jump-start it we think we need to build an additional 29 or 30 ships in the first seven years,” he said.

“When you do all that math, it’s a lot of money that we don’t have. But we were asked to deliver on that, so we’ve passed along what we think it would take. And obviously, any number you give in this environment is going to be sticker shock. So that’s why I say don’t take me literally, all it is is a math equation right now.”…

“We definitely wanted to go after SSNs, DDGs and carriers, to get carriers from a five year center to a four year center and even looked at a three year option. So the numbers I will give to you are reflective of those three priorities, because those are the big impacters in any competition at sea,” he told USNI News.

“Amphibs come later, but I’m talking about initial, what are we building that we can stamp out that are good. We know how to build Virginia class, we know how to build DDGs.”…

Moran said during his presentation that the Navy is currently on track to hit 310 ships if the Fiscal Year 2017 spending bill is passed by Congress this spring after an extended continuing resolution, the Navy would finish buying the last ships that will eventually push it to 310.

Without this quick ramp up of shipbuilding, though, the Navy won’t just fail to reach 355 ships but will actually slip back below 300 ships, he said. Dozens of ships built during the Reagan era buildup are headed for decommissioning in the 2020s and the Navy needs to act quickly to either replace them at pace and stay around 310, or ramp up even faster to grow the fleet.

The vice chief told reporters that the plan for a 355 trajectory includes building more destroyers, building carriers faster, and maintaining two SSNs a year even as the new Columbia class ballistic missile submarine begins production. A Columbia class SSBN is the equivalent of about two SSNs, meaning the submarine industrial base would see about double the workload in any given year under this plan.24

CRS analysis of the Navy’s February 2017 white paper suggests that the figure of $150 billion mentioned above is a hybrid cost figure that includes the following amounts shown in the white paper:

• $32.2 billion in additional shipbuilding costs for the five year period FY2017-FY2021;

• $55.1 billion in total shipbuilding costs (i.e., both previously planned shipbuilding for the previously planned 308- ship fleet, plus additional shipbuilding for the 355-ship fleet) for the two-year period FY2022-FY2023;

• $29.6 billion in additional aircraft procurement costs for the five-year period FY2017-FY2021; and

• $35.4 billion in total aircraft procurement costs (i.e., both previously planned aircraft procurement for previously planned 308-ship fleet, plus additional aircraft procurement for the 355-ship fleet) for the two-year period FY2022-FY2023.

The sum total of the above four figures a hybrid sum that mixes together both additional shipbuilding and aircraft procurement costs for FY2017-FY2021 and total shipbuilding and aircraft procurement costs for FY2022-FY2023—is $152.3 billion.

Shipbuilding Plus Operation and Support (O&S) costs

As shown in Table 1, the above additional shipbuilding and aircraft procurement funds are only a fraction of the total costs that would be needed to achieve and maintain the Navy’s 355-ship fleet instead of the Navy’s previously envisaged 308-ship fleet. CBO estimates that, adding together both shipbuilding costs and ship operation and support (O&S) costs, the Navy’s 355-ship fleet would cost an average of about $11 billion to $23 billion more per year in constant FY2017 dollars than the Navy’s previously envisaged 308-ship fleet. This figure does not include additional costs for manned aircraft, unmanned systems, and weapons.25 (CRS estimates that a total of roughly 15,000 additional sailors and aviation personnel might be needed for the 47 additional ships.)26

Industrial Base Ability for Taking on Additional Shipbuilding Work

Navy officials have stated that, in general, the shipbuilding industrial base has the ability to take on the additional shipbuilding work needed to achieve and maintain a 355-ship fleet, and that building toward the 355-ship goal sooner rather than later would be facilitated by ramping up production of existing ship designs rather than developing and then starting production of new designs.

Ramping up to higher rates of shipbuilding would require additional tooling and equipment at some shipyards and some supplier firms. Additional production and supervisory workers would need to be hired and trained at shipyards and supplier firms. Depending on their specialties, newly hired workers could be initially less productive per unit of time worked than more experienced workers. Given the time needed to increase tooling and hire and train new workers, some amount of time would be needed to ramp up to higher shipbuilding rates—production could not jump to higher rates overnight.27 Some parts of the shipbuilding industrial base could face more challenges than others in ramping up to the higher production rates required to build the various parts of the 355-ship fleet. As stated in the April 2017 CBO report,

all seven shipyards would need to increase their workforces and several would need to make improvements to their infrastructure in order to build ships at a faster rate. However, certain sectors face greater obstacles in constructing ships at faster rates than others: Building more submarines to meet the goals of the 2016 force structure assessment would pose the greatest challenge to the shipbuilding industry. Increasing the number of aircraft carriers and surface combatants would pose a small to moderate challenge to builders of those vessels. Finally, building more amphibious ships and combat logistics and support ships would be the least problematic for the shipyards. The workforces across those yards would need to increase by about 40 percent over the next 5 to 10 years.

Managing the growth and training of those new workforces while maintaining the current standard of quality and efficiency would represent the most significant industrywide challenge. In addition, industry and Navy sources indicate that as much as $4 billion would need to be invested in the physical infrastructure of the shipyards to achieve the higher production rates required under the [notional] 15- year and 20-year [buildup scenarios examined by CBO]. Less investment would be needed for the [notional] 25- year or 30 year [buildup scenarios examined by CBO].28

A revised Navy FY2017 unfunded priorities list (UPL)29 submitted to Congress in January 2017 included, as line item 36, an unfunded item for $255 million in military construction (MilCon) and Other Procurement, Navy (OPN) funding for production facilities at the General Dynamics/Electric Boat submarine production facility at Quonset Point, RI, to facilitate increasing the attack submarine procurement rate to three boats per year.30 A January 13, 2017, press report states:

The Navy’s production lines are hot and the work to prepare them for the possibility of building out a much larger fleet would be manageable, the service’s head of acquisition said Thursday.

From a logistics perspective, building the fleet from its current 274 ships to 355, as recommended in the Navy’s newest force structure assessment in December, would be straightforward, Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development and Acquisition Sean Stackley told reporters at the Surface Navy Association’s annual symposium.

“By virtue of maintaining these hot production lines, frankly, over the last eight years, our facilities are in pretty good shape,” Stackley said. “In fact, if you talked to industry, they would say we’re underutilizing the facilities that we have.” The areas where the Navy would likely have to adjust “tooling” to answer demand for a larger fleet would likely be in Virginia-class attack submarines and large surface combatants, the DDG-51 guided missile destroyers two ship classes likely to surge if the Navy gets funding to build to 355 ships, he said.

“Industry’s going to have to go out and procure special tooling associated with going from current production rates to a higher rate, but I would say that’s easily done,” he said. Another key, Stackley said, is maintaining skilled workers

both the builders in the yards and the critical supply chain vendors who provide major equipment needed for ship construction. And, he suggested, it would help to avoid budget cuts and other events that would force work force layoffs.

“We’re already prepared to ramp up,” he said. “In certain cases, that means not laying off the skilled workforce we want to retain.”31

A January 17, 2017, press report states:

Building stable designs with active production lines is central to the Navy’s plan to grow to 355 ships. “if you look at the 355-ship number, and you study the ship classes (desired), the big surge is in attack submarines and large surface combatants, which today are DDG-51 (destroyers),” the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Sean Stackley, told reporters at last week’s Surface Navy Association conference. Those programs have proven themselves reliable performers both at sea and in the shipyards.

From today’s fleet of 274 ships, “we’re on an irreversible path to 308 by 2021. Those ships are already in construction,” said Stackley. “To go from there to 355, virtually all those ships are currently in production, with some exceptions: Ohio Replacement, (we) just got done the Milestone B there (to move from R&D into detailed design); and then upgrades to existing platforms. So we have hot production lines that will take us to that 355-ship Navy.”32

A January 24, 2017, press report states:

Navy officials say a recently determined plan to increase its fleet size by adding more new submarines, carriers and destroyers is “executable” and that early conceptual work toward this end is already underway….

Although various benchmarks will need to be reached in order for this new plan to come to fruition, such as Congressional budget allocations, Navy officials do tell Scout Warrior that the service is already working at least in concept on plans to vastly enlarge the fleet. Findings from this study are expected to inform an upcoming 2018 Navy Shipbuilding Plan, service officials said.33

A January 12, 2017, press report states:

Brian Cuccias, president of Ingalls Shipbuilding [a ship yard owned by Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) that builds Navy destroyers and amphibious ships as well as Coast Guard cutters], said Ingalls, which is currently building 10 ships for four Navy and Coast Guard pro- grams at its 800-acre facility in Pascagoula, Miss., could build more because it is using only 70 to 75 percent of its capacity.34

A March 2017 press report states:

As the Navy calls for a larger fleet, shipbuilders are looking toward new contracts and ramping up their yards to full capacity….

The Navy is confident that U.S. shipbuilders will be able to meet an increased demand, said Ray Mabus, then- secretary of the Navy, during a speech at the Surface Navy Association’s annual conference in Arlington, Virginia.

They have the capacity to “get there because of the ships we are building today,” Mabus said. “I don’t think we could have seven years ago.”

Shipbuilders around the United States have “hot” production lines and are manufacturing vessels on multi-year or block buy contracts, he added. The yards have made investments in infrastructure and in the training of their workers.

“We now have the basis … [to] get to that much larger fleet,” he said. Shipbuilders have said they are prepared

for more work.

At Ingalls Shipbuilding—a subsidiary of Huntington Ingalls Industries 10 ships are under construction at its Pascagoula, Mississippi, yard, but it is under capacity, said Brian Cuccias, the company’s president.

The shipbuilder is currently constructing five guided- missile destroyers, the latest San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock ship, and two national security cutters for the Coast Guard.

“Ingalls is a very successful production line right now, but it has the ability to actually produce a lot more in the future,” he said during a briefing with reporters in January.

The company’s facility is currently operating at 75 percent capacity, he noted…. Austal USA the builder of the Independence-variant of the littoral combat ship and the expeditionary fast transport vessel—is also ready to increase its capacity should the Navy require it, said Craig Perciavalle, the company’s president. The latest discussions are “certainly something that a shipbuilder wants to hear,” he said. “We do have the capability of increasing throughput if the need and demand were to arise, and then we also have the ability with the present workforce and facility to meet a different mix that could arise as well.”

Austal could build fewer expeditionary fast transport vessels and more littoral combat ships, or vice versa, he added.

“The key thing for us is to keep the manufacturing lines hot and really leverage the momentum that we’ve gained on both of the programs,” he said.

The company which has a 164 acre yard in Mobile, Alabama—is focused on the extension of the LCS and expeditionary fast transport ship program, but Perciavalle noted that it could look into manufacturing other types of vessels.

“We do have excess capacity to even build smaller vessels

… if that opportunity were to arise and we’re pursuing that,” he said.

Bryan Clark, a naval analyst at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, said shipbuilders are on average running between 70 and 80 percent capacity. While they may be ready to meet an increased demand for ships, it would take time to ramp up their workforces.

However, the bigger challenge is the supplier industrial base, he said.

“Shipyards may be able to build ships but the supplier base that builds the pumps … and the radars and the radios and all those other things, they don’t necessarily have that ability to ramp up,” he said. “You would need to put some money into building up their capacity.”

That has to happen now, he added.

Rear Adm. William Gallinis, program manager for pro- gram executive office ships, said what the Navy must be “mindful of is probably our vendor base that support the shipyards.”

Smaller companies that supply power electronics and switchboards could be challenged, he said.

“Do we need to re-sequence some of the funding to pro- vide some of the facility improvements for some of the vendors that may be challenged? My sense is that the industrial base will size to the demand signal. We just need to be mindful of how we transition to that increased demand signal,” he said.

The acquisition workforce may also see an increased amount of stress, Gallinis noted. “It takes a fair amount of experience and training to get a good contracting officer to the point to be [able to] manage contracts or procure contracts.”

“But I don’t see anything that is insurmountable,” he added.35

Employment Impact of Additional Shipbuilding Work

Depending on the number of additional ships per year that might be added to the Navy’s shipbuilding effort, building the additional ships that would be needed to achieve and maintain the 355-ship fleet could create thousands of additional manufacturing (and other) jobs at shipyards, associated supplier firms, and elsewhere in the U.S. economy.

Consistent with U.S. law, the seven shipyards that build most of the Navy’s major ships are all located in the United States.36 As of 2016, these seven yards reportedly employed a total of more than 66,000 people.37 Production workers account for a sizeable fraction of that figure. Some of the production workers are assigned to projects other than building Navy ships.38 (The remaining employees at the yards include designers and engineers, management and supervisory staff, and administrative and support staff.) Navy shipbuilding additionally supports thousands of manufacturing and other jobs at hundreds of supplier firms located throughout the United States. (Some states have more of these firms, while others have fewer of them.)

Shipbuilding can also have broader effects on the U.S. economy. A 2015 Maritime Administration (MARAD) report states, “Considering the indirect and induced impacts, each direct job in the shipbuilding and repairing industry is associated with another

2.6 jobs in other parts of the US economy; each dollar of direct labor income and GDP in the shipbuilding and repairing industry is associated with another $1.74 in labor income and $2.49 in GDP, respectively, in other parts of the US economy.”39

A March 2017 press report states, “Based on a 2015 economic impact study, the Shipbuilders Council of America [a trade association for U.S. shipbuilders and associated supplier firms] believes that a 355-ship Navy could add more than 50,000 jobs nationwide.”40 The 2015 economic impact study referred to in that quote might be the 2015 MARAD study discussed in the previous paragraph. An estimate of more than 50,000 additional jobs nationwide might be viewed as a higher end estimate; other estimates might be lower.

Navy Desire to Improve Ship Readiness Before Expanding Fleet

Navy officials have indicated that, prior to embarking on a fleet expansion, they would first like to see additional funding provided for overhaul and repair work to improve the readiness of existing Navy ships, particularly conventionally powered surface ships, and for mitigating other shortfalls in Navy readiness.41

A December 12, 2016, press report states:

Despite President elect Donald Trump’s goal of building toward a 350-ship Navy, the service’s immediate priorities under an increased budget would be catching up on ship and aircraft maintenance, as well as buying more strike fighters and munitions, according to a top officer.

Eying the potential for increased military spending under Trump’s administration, the Navy is developing a list of priorities the service has if more funding becomes available, according to Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran.

“Maintenance and modernization for ships, submarines and aircraft are at the top of our list,” Moran told reporters. 42

A January 11, 2017, press report similarly states:

Speaking at the Surface Navy Association’s annual symposium near Washington, D.C., on Tuesday, Moran said Navy leaders have already told President-elect Donald Trump’s transition team that they want any additional funding that comes available within this fiscal year to go to maintenance first.

“The transition team came around to all of us in the building and asked us what we could do with more money right now,” Moran said. “The answer was not, ‘Buy more ships.’ The answer was, ‘Make sure that the 274 that we had were maintained and modernized to provide 274 ships’ worth of combat time.’ Then, we’ll start buying more ships.”43

Another January 11, 2017, press report similarly states:

The message Navy leaders are sending to President elect Donald Trump’s team is: We need money to keep the current 274 ships in the fleet maintained and modernized first and then give us the money to buy more ships….

In talking with the press and in his address, he said, “It is really hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel” if maintenance is continuously deferred, causing ships to be in the yards far longer in the yards than expected with costs rising commensurately.

“Deferred maintenance is insidiously taking its toll.”

Not only does this add greater risk and a growing gap between the combatant commanders’ requirements and what the service can deliver, “you can’t buy back that experience” and proficiency sailors lose when they can’t use their skills at sea.

“At some point, we have to dig ourselves out of the hole,” Moran said in his address.44

A January 24, 2017, press report states:

The Navy wants $2 billion in additional funding this year for much needed ship maintenance and fleet operations, and would also buy two dozen Super Hornets and an additional San Antonio class amphibious warship if money were made available, according to an early January draft wish list obtained by USNI News.

While the list is not as official as the February 2016 Unfunded Priorities List from which it stems, it is meant to be a conversation-starter with Congress and the new Trump Administration on the Navy’s needs for today and in the near term, a senior service official told USNI News on Tuesday. The main message of that conversation is that current readiness must be addressed first, with acquisitions wishes being addressed afterwards with whatever funding may remain, a senior Navy official told USNI News.

“Our priorities are unambiguously focused on readiness those things required to get planes in the air, ships and subs at sea, sailors trained and ready,” the official said….

The first section of the updated list addresses afloat readiness, which both the Navy and the new Trump Administration have said would be a primary focus of any FY 2017 supplemental….

More than $500 million for air operations and flying hours, as well as $339 million for ship operations and

$647 for ship depot maintenance, sit atop the wish list. These items were included in the original UPL but have been prioritized first in this most recent version….

Earlier this month Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran said that, while President Donald Trump had expressed interest in growing the Navy fleet, readiness needed to be a top priority before growing a larger fleet. “Deferred maintenance is insidiously taking its toll,” he said, and “at some point, we have to dig ourselves out of the hole” that has been created from years of too little funding for operations and maintenance.45

Another January 24, 2017, press report similarly states:

With no fiscal 2017 defense budget in sight and little chance of an agreement before April if then the military services are submitting second and possibly third rounds of unfunded requirements lists to Congress. The lists include items left out of the original budget requests, ranked in order of priority should Congress find a way to fund them.

The latest list from the US Navy was sent to Congress Jan. 5, updating a similar list sent over at the end of February but rejiggered in light of the new 355 ship Force Structure Assessment, changes in requirements and the lateness of the fiscal year, which limit what can be done in the current budget. The new list also reflects what Navy leaders have been saying in recent weeks they need most— maintenance funding. While the late February list lead off with acquisition needs, the new top priorities include $2 billion in afloat readiness funding….

The maintenance needs reflect Navy decisions in recent years to put off upkeep and protect long-term procurement accounts from successive cuts mandated by the Budget Control Act also known as sequestration. But recent statements from top Navy brass underscore the need to restore maintenance money.

“Our priorities are unambiguously focused on readiness — those things required to get planes in the air, ships and subs at sea, sailors trained and ready,” the Navy official declared. “No new starts.”46

ENDNOTES

1. The Navy states that [the] Navy’s Force Structure Assessment (FSA) was developed in an effort to determine the right balance of existing forces, the ships we currently have under construction and the future procurement plans needed to address the ever evolving and increasingly complex threats the Navy is required to counter in the global maritime commons….

The number and mix of ships in the objective force, identified by this FSA, reflects an in depth assessment of the Navy’s force structure requirements it also includes a level of operational risk that we are willing to assume based on the resource limitations under which the Navy must operate.

While the force levels articulated in this FSA are adjudged to be successful in the scenarios defined for Navy combat, that success will likely also include additional loss of forces, and longer timelines to achieve desired objectives, in each of the combat scenarios against which we plan to use these forces. It should not be assumed that this force level is the “desired” force size the Navy would pursue if resources were not a constraint rather, this is the level that balances an acceptable level of warfighting risk to our equipment and personnel against available resources and achieves a force size that can reasonably achieve success….

In January, the 2016 FSA started with a request to the Combatant Commanders (CCDRs) to provide their unconstrained desire for Navy forces in their respective theaters. In order to fully resource these platform specific demands, with very little risk in any theater while still supporting enduring missions and ongoing operations, the Navy would be required to double its current annual budget, which is essentially unrealistic in both current and expected future fiscal environments. After identifying instances where forces were being requested for redundant missions or where enduring force levels were not required, while also looking at areas where we could take some risk in mission success or identify a new way to accomplish the mission, we were able to identify an FSA force level better aligned with resources available….

In order to assess warfighting risk and identify where margins existed that could be reduced, we did an in depth review and analysis of “what it takes to win”, on what timeline, and in which theater, for each major ship class. The goal of this phase of the analysis was to determine the minimum force structure that: complies with defense planning guidance directed combinations of challenges for force sizing and shaping; meets approved Day 0 and warfighting response timelines; [and] delivers future steady state and warfighting requirements, determined by Navy’s analytic process, with an acceptable degree of risk (e.g. does not jeopardize joint force campaign success).

2. For more on China’s naval modernization effort, see CRS Report RL33153, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

3. See, for example, Dave Majumdar, “Chief of Naval Operations Richardson: US Navy is Focusing on Enemy Submarine Threat,” National Interest, August 30, 2016; Dmitry Gorenburg, “Black Sea Fleet Projects Power Westward,” Russian Military Reform, July 20, 2016; Dave Majumdar, “Russia’s Submarine Force Is Back: How Worried Should America Be?” National Interest, July 5, 2016; Sa, LaGrone, “Admiral Warns: Russian Subs Waging Cold War Style ‘Battle of the Atlantic,’” USNI News, June 3, 2016; Jim Sciutto et al., “CNN Visits Nuclear Submarine As Deep-Sea Tensions with Russia Grow,” CNN, May 5, 2016; Eric Schmitt, “Russia Bolsters Its Submarine Fleet, and Tensions With

U.S. Rise,” New York Times, April 20, 2016; Jim Sciutto, “Top Navy Official: Russian Sub Aggression at Peak Since Cold War,” CNN, April 15, 2016; Franz- Stefan Gady, “Russian Sub Combat Patrols Nearly Doubled in 2015,” The Diplomat, March 23, 2016; Karl Soper, “Russia Confirms Higher Level of Submarine Activity,” IHS Jane’s 360, March 23, 2016; Magnus Nordenman, “Russian Subs Are Reheating a Cold War Chokepoint,” Defense One, March 4, 2016; Richard Lardner, “US Commander Says Tracking Russian Subs Is a Key Challenge,” CNBC, March 1, 2016; Paul McLeary, “Chinese, Russian Subs Increasingly Worrying the Pentagon,” Foreign Policy, February 24, 2016; Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “Report: Russian Sub Activity Returns to Cold War Levels,” Washington Post, February 4, 2016; Nicholas de Larrinaga, “Russian Submarine Activity Topping Cold War Levels,” IHS Jane’s 360, February 2, 2016.

4. See, for example, Justin Doubleday, “CNO: High Optempo Hindering Seven- Month Deployment Goal,” Inside the Navy, September 19, 2016; Chris Church, “Analysts: Truman Strike Group Extension Highlights Flaws in Navy’s Deployment Goal,” Stars and Stripes, May 5, 2016; David Larter, “Navy Leader Warns Long Deployments Will Harm the Fleet,” Navy Times, April 20, 2016; Hope Hodge Seck, “Overtaxed Fleet Needs Shorter Deployments,” Military.com, March 19, 2016; David Larter, “Carrier Scramble: CENTCOM, PACOM Face Flattop Gaps This Spring Amid Tensions,” Navy Times, January 7, 2016; Bryan Clark and Jesse Sloman, Deploying Beyond Their Means, America’s Navy and Marine Corps at a Tipping Point, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2015, 28 pp.; Ryan T. Tewell, “Assessing the U.S. Aircraft Carrier Gap in the Gulf,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 5, 2015. 5 See, for example, Hope Hodge Seck, “CNO: Navy to Hit Seven-Month Deployments by End of Year,” Military.com, February 12, 2016; Chris Church, “Analysts: Truman Strike Group Extension Highlights Flaws in Navy’s Deployment Goal,” Stars and Stripes, May 5, 2016; David Larter, “Navy Leader Warns Long Deployments Will Harm the Fleet,” Navy Times, April 20, 2016; Hope Hodge Seck, “Overtaxed Fleet Needs Shorer Deployments,” Military.com, March 19, 2016; Bryan Clark and Jesse Sloman, Deploying Beyond Their Means, America’s Navy and Marine Corps at a Tipping Point, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2015, 28 pp.; David Larter, “CNO: Shorter Carrier Cruises A Year Away,” Navy Times, February 28, 2015; David Larter, “Uneven Burden: Some Ships See Time at Sea Surge; Others Fall Well Below Fleetwide Average,” Navy Times, June 16, 2014; Richard Sisk, “Struggle Ahead to Reach

8-Month Sea Deployments,” Military.com, April 8, 2016; David Larter, “Navy Fleet Boss: 9-Month Deployments Unsustainable,” Military Times, April 8, 2014; Lance M. Bacon, “Fleet’s New Deployment Plan To Lock In 8-Month Cruises,” Defense News, April 6, 2014.

6. Spoken testimony of Admiral Jonathan Greenert at a March 12, 2014, hearing before the House Armed Services Committee on the Department of the Navy’s proposed FY2015 budget, as shown in transcript of hearing.

7. U.S. Navy, Executive Summary, 2016 Navy Force Structure Assessment (FSA), December 15, 2016, p. 1. See also United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, 14 pp., with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

8. “Presidential Memorandum on Rebuilding the U.S. Armed Forces,” accessed January 31, 2017, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press- office/2017/01/27/presidential-memorandum-rebuilding-us-armed-forces.

9. “National Defense, Donald J. Trump’s Vision,” accessed January 19, 2017, at https://www.donaldjtrump.com/policies/national-defense.

10. William J. Perry et al., Ensuring a Strong U.S. Defense for the Future: The National Defense Panel Review of the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review, Washington, 2014, p. 3. The statement appears again on page 49.

11. Stephen J. Hadley and William J. Perry, co-chairmen, et al., The QDR in Perspective: Meeting America’s National Security Needs In the 21st Century, The Final Report of the Quadrennial Defense Review Independent Panel, Washington, 2010, Figure 3-2 on pages 58-59.

12. Department of Defense, Report on the Bottom-Up Review, October 1993, Figure 7 on page 28. For further discussion of the 1993 BUR, see CRS Report R43838, A Shift in the International Security Environment: Potential Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O’Rourke.

13. The term high-low mix refers to a force structure consisting of some mix of individually more-capable (and more expensive) units, and individually less- capable (and less-expensive) units.

14. William J. Perry et al., Ensuring a Strong U.S. Defense for the Future: The National Defense Panel Review of the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review, Washington, 2014, p. 3. The statement appears again on page 49.

15. Information provided by CBO to CRS on April 26, 2017, reflecting information in Congressional Budget Office, Costs of Building a 355-Ship Navy, April 2017, 12 pp.

16. United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, 14 pp., with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

17. United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, p. 4, with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

18. United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, p. 8, with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

19. Congressional Budget Office, Costs of Building a 355-Ship Navy, April 2017,

p. 1.

20. Information provided by CBO to CRS on April 26, 2017, reflecting information in Congressional Budget Office, Costs of Building a 355-Ship Navy, April 2017, 12 pp.

21. United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, p. 10, with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

22. Information provided by CBO to CRS on April 26, 2017, reflecting information in Congressional Budget Office, Costs of Building a 355-Ship Navy, April 2017, p. 3. The same figure is mentioned on page 7.

23. United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, p. 14, with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

24. Megan Eckstein, “Moran: Navy Needs As Much As $150B Extra to ‘Jump- Start’ Path to 355 Ships; Would Buy Mostly DDGs, SSNs, Carriers,” USNI News, March 22, 2017.

25. Information provided by CBO to CRS on April 26, 2017, reflecting information in Congressional Budget Office, Costs of Building a 355-Ship Navy, April 2017, 12 pp.

26. The rough estimate of 15,000 additional sailors is based on Navy ship crew sizes as shown in the Navy’s online Fact File (http://www.navy.mil/navydata/fact.asp), and includes the following:

• about 2,376 sailors for 18 additional attack submarines (132 per boat);

• about 4,500 sailors for 1 additional aircraft carrier (including about 3,000 to operate the ship and about 1,500 to operate its embarked air wing);

• about 5,264 sailors for 16 additional destroyers (329 per ship);

• about 1,520 sailors for 4 additional amphibious ships (380 per ship);

• about 18 sailors for 3 additional combat logistics force ships (6 per ship—these ships have mostly civilian crews);

• about 750 sailors for 3 additional expeditionary support base ships (ESBs) (about 250 per ship, depending on the mission—these ships also have 34 additional Military Sealift Command personnel); and

• additional sailors for the 2 additional command and support ships.

The figures above exclude any additional sailors that might be needed ashore in support roles.

27. For further discussion regarding the challenges of expanding shipyard workforces, see Mike Stone, “Missing from Trump’s Grand Navy Plan: Skilled

Workers to Build the Fleet,” Reuters, March 17, 2017; and James Bach, “Massive Navy Expansion May Be Easier Said Than Done for U.S. Shipbuilders,” Washington Business Journal, March 3, 2017.

28. Congressional Budget Office, Costs of Building a 355-Ship Navy, April 2017,

pp. 9-10.

29. A UPL (also sometimes called an unfunded requirements list, or URL) is a list of items that are not funded in the service’s budget request that the service has identified as its priorities for receiving any additional funding that Congress might decide to provide to the service as part of its markup of the service’s requested budget.

30. Navy information paper entitled “Revised FY 2017 Unfunded Priorities List,” January 5, 2017, p. 2. The document was posted at DefenseNews.com on January 24, 2017.

31. Hope Hodge Seck, “Navy Acquisition Chief: Surge to 355 Ships ‘Easily Done,’” DoD Buzz, January 13, 2017.

32. Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Build More Ships, But Not New Designs: CNO Richardson To McCain,” Breaking Defense, January 17, 2017.

33. Kris Osborn, “Navy: Larger 355-Ship Fleet—‘Executable,’” Scout Warrior, January 24, 2017.

34. Marc Selinger, “Navy Needs More Aircraft to Match Ship Increase, Secretary [of the Navy] Says,” Defense Daily, January 12, 2017. See also Lee Hudson, “Ingalls Operating at About 75 Percent Capacity, Provided Info to Trump Team,” Inside the Navy, January 16, 2017.

35. Yasmin Tadjdeh, “Navy Shipbuilders Prepared for Proposed Fleet Buildup,”

National Defense, March 2017.

36. 10 USC 7309 states:

§7309. Construction of vessels in foreign shipyards: prohibition

A. Prohibition.-Except as provided in subsection (b), no vessel to be con- structed for any of the armed forces, and no major component of the hull or superstructure of any such vessel, may be constructed in a foreign shipyard.

B. Presidential Waiver for National Security Interest.- (1) The President may authorize exceptions to the prohibition in subsection (a) when the President determines that it is in the national security interest of the United States to do so.

(2) The President shall transmit notice to Congress of any such determination, and no contract may be made pursuant to the exception authorized until the end of the 30-day period beginning on the date on which the notice of the determination is received by Congress.

C. Exception for Inflatable Boats. An inflatable boat or a rigid inflatable boat, as defined by the Secretary of the Navy, is not a vessel for the purpose of the restriction in subsection (a).

In addition, the paragraph in the annual DOD appropriations act that makes appropriations for the Navy’s primary shipbuilding account (the Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy, or SCN, account) typically includes provisions stating “Provided further, That none of the funds provided under this heading for the construction or conversion of any naval vessel to be constructed in shipyards in the United States shall be expended in foreign facilities for the construction of major components of such vessel: Provided further, That none of the funds provided under this heading shall be used for the construction of any naval vessel in foreign shipyards.”

37. Two of these seven shipyards—Newport News Shipbuilding of Newport News, VA, and Ingalls Shipbuilding of Pascagoula, MIS—are owned by Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII). HII’s primary activities are building new submarines and aircraft carriers and performing mid-life refueling overhauls of existing aircraft carriers. HII states that it employed a total of almost 37,000 people as of January 2017. (Source: HII website, http://www.huntingtoningalls.com/, accessed January 26, 2017.)

Three of these seven shipyards Bath Iron Works of Bath, ME; the Electric Boat division of Groton, CT, and Quonset Point, RI; and National Steel and Shipbuilding Company (NASSCO) in San Diego, CA—are owned by General Dynamics (GD). GD reportedly employed a total of roughly 23,600 people at these three shipyards as of 2016, with the breakdown as follows:

• GD/BIW reportedly employed 6,100 people as of September 2016. (Source: Beth Brogan, “Bath Iron Works cuts 160 jobs, including layoff of 30 workers,” Bangor Daily News, September 23, 2016.).

• GD/EB reportedly employed about 14,000 people as of 2016. (Source: Stephen Singer, Electric Boat To Hire Thousands As Military Strategy Shifts Back To Subs, Hartford Courant, April 18, 2016. The article states:

• “As many as 850 high-skilled, well-paid manufacturing and other jobs are being filled this year and nearly 4,000 in the next 15 years, establishing a workforce of 18,000 at the submarine manufacturer’s sites in Groton and Quonset Point, R.I.”)

• GD/NASSCO reportedly employed about 3,500 people as of October 2016. (Source: Chris Jennewein,

• “NASSCO Warns Employees 700 Layoffs May Be Coming in January,” Times of San Diego, October 25, 2016.)

The remaining two shipyards are Fincantieri/Marinette Marine of Marinette, WI, and Austal USA of Mobile, AL. Both yards build Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs), and Austal USA additionally builds Expeditionary Fast Transports (EPFs these ships were previously called Joint High Speed Vessels, or JHSVs). As of March 2016, Marinette Marine reportedly employed more than 2,000 people and Austal USA reportedly employed more than 4,000 people. (Source: Allyson Versprille, “LCS Cuts Could Strain Shipbuilding Industry,” National Defense, March 2016.)

38. For example, at HII/Newport News Shipbuilding, a sizeable fraction of the production workforce is assigned to midlife nuclear refueling overhauls of existing aircraft carriers. At HII/Ingalls, some production workers are assigned to building national Security Cutters (NSCs) for the Coast Guard. At GD/NASSCO, some production workers may be assigned to the production of commercial cargo ships.

39. Maritime Administration (MARAD), The Economic Importance of the U.S. Shipbuilding and Repairing Industry, November 2015, pp. E-3, E-4, For another perspective on the issue of the impact of shipbuilding on the broader economy, see Edward G. Keating et al, The Economic Consequences of Investing in Shipbuilding, Case Studies in the United States and Sweden, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 2015 (Report RR-1036), 69 pp.

40. Yasmin Tadjdeh, “Navy Shipbuilders Prepared for Proposed Fleet Buildup,” National Defense, March 2017. Similarly, another press report states: “The Navy envisioned by Trump could create more than 50,000 jobs, the Shipbuilders Council of America, a trade group representing U.S. shipbuilders, repairers and suppliers, told Reuters.” (Mike Stone, “Missing from Trump’s Grand Navy Plan: Skilled Workers to Build the Fleet,” Reuters, March 17, 2017.)

41. In addition to the press reports cited here, see also United States Navy Accelerated Fleet Plan, undated, pp. 2-4, with cover memorandum from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of Defense, February 9, 2017, posted at InsideDefense.com (subscription required) April 6, 2017.

42. Justin Doubleday, “Maintenance, Modernization Are Navy’s Priorities Under Higher Topline,” Inside the Navy, December 12, 2016.

43. Hope Hodge Seck, “Navy to Trump Team: Fund Maintenance Before Buying New Ships,” DoD Buzz, January 11, 2017.

44. John Grady, “Navy to Trump: We Need Maintenance Funded Before New Ships,” USNI News, January 11, 2017.

45. Megan Eckstein, “Update to Navy Unfunded Priorities List Emphasizes Readiness; Would Add More Super Hornets, Additional Amphib,” USNI News, January 24, 2017.

46. Hope Hodge Seck, “Navy to Trump Team: Fund Maintenance Before Buying New Ships,” DoD Buzz, January 11, 2017.