It’s a pleasure once again to talk to the Naval Submarine League. I particularly enjoy this one because not only does it represent the nearing of the end of the calendar year and the beginning of the budget season, but it’s also an opportunity to see so many old friends that come particularly to this one, which is nice. What I’m going to talk about today are a series of things that are really focused around the challenges and opportunities that are confronting the Submarine Force as we move through the next couple of decades.

I will talk about the Submarine Unified Build Strategy, giving you more information on that than we have in the past, and let you know what we’ve been doing over the last year to position ourselves to take on those challenges and opportunities. I will, of course, address the highest priorities of the Submarine Force, the OHIO Replacement SSBN and the two per year VIRGINIA Class submarines with Virginia Payload Module. I will then finish up with a brief touch point on SSN(X) and what we’re looking for in the future beyond the VIRGINIA Class submarine.

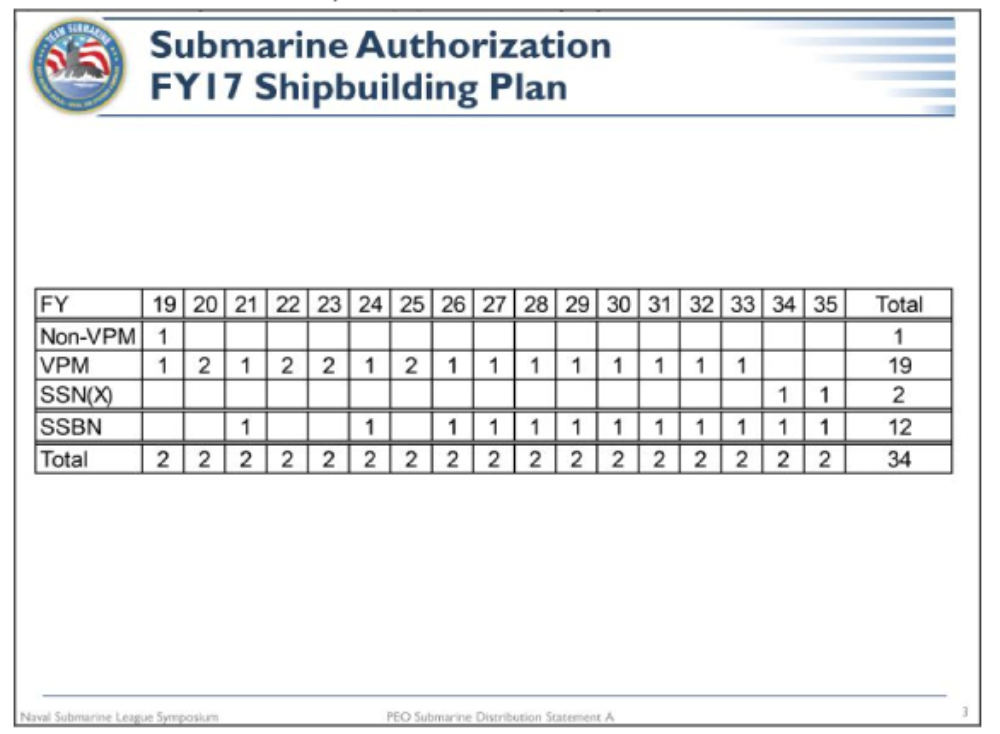

If you look at this, this is the fiscal year ‘17 shipbuilding plan as it pertains to submarines. It’s the same as it was last year, but there are several things that you need to look at and understand as you look at the numbers on the page. The first thing I’d draw your attention to is the unbroken string of twos across the bottom of the chart.

Compared to where we have been in the past, that’s a good thing. We are building two submarines every year and we will continue to do so in the future. But if you look more closely, you’ll see that every year we authorize an OHIO Replacement SSBN we are only planning to build one VIRGINIA Class submarine.

That is a significant problem for the Navy and for the Submarine Force. There’s an opportunity for us to fix it, and we’re working very hard to do so. I’ll spend a good bit of today’s remarks talking about that. The two per year VIRGINIA Class shortfalls represented by those ones in the VIRGINIA with VPM line, are one of our highest priorities for changes in the submarine build plan.

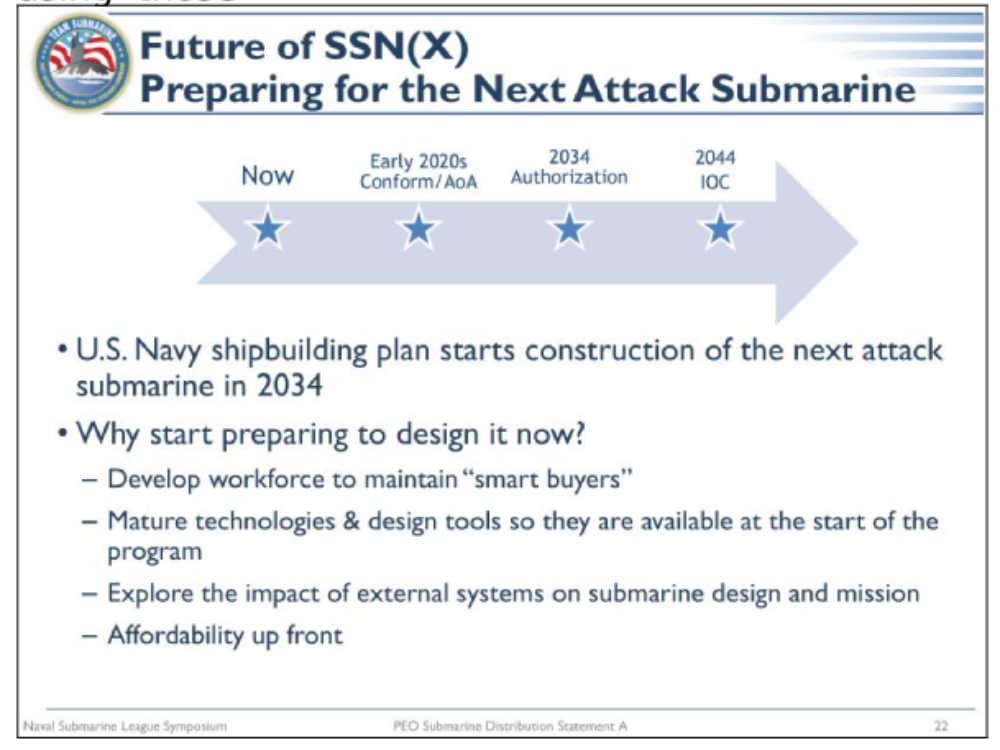

The final thing I’ll call your attention to is the SSN(X) line that starts in 2034. That’s one year before we authorize the final SSBN, and then that continues on after the completion of Block VII VIRGINIA Class. So we’ll talk more about that at the end as well.

The OHIO Replacement is, of course, the Navy’s highest priority, as the CNO has said. That was actually in the video that Admiral Tofalo played for us. Admiral Caldwell said it. Admiral Tofalo said it. Hopefully you will hear every speaker here this week say it. It is our highest priority.

The Navy is going to build 12 OHIO Replacement SSBNs. It’s my job as PEO Submarines to both make sure they are delivered on time, and then control cost and reduce it even as much as possible, to ensure that the Navy has adequate funding to build the rest of the Navy it needs. Whether that’s additional VIRGINIA Class submarines or additional surface ships or additional aviation assets, it all comes out of the Navy’s topline unless we get topline relief. So I have to control the cost of OHIO Replacement so we continue to afford the Navy that we need.

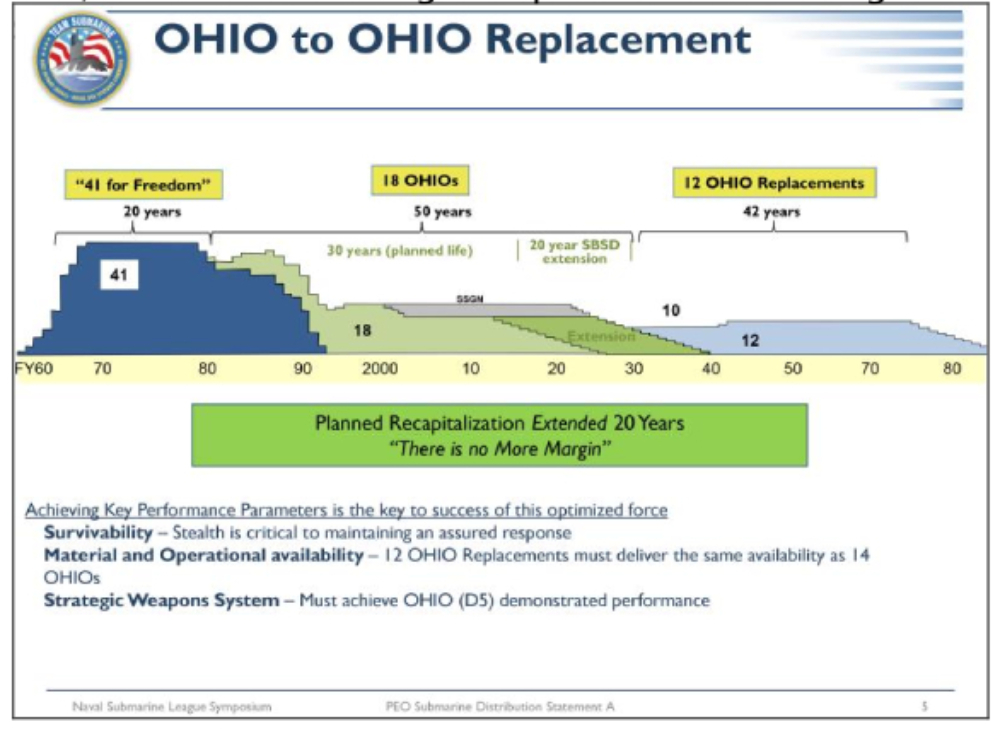

A couple of things, as you look at this chart, are interesting. One of the things I like to drop anchor and talk about a little bit is how well we have done at improving the product that we use in strategic deterrence. The large blue hump there, the ‘41 for Freedom, was our initial foray into ballistic missile launch from submarines. They were only designed for 20 years. Some of them didn’t make it that long, for a variety of reasons. As a result, we needed a large number of them to carry out the strategic deterrence mission.

It was greatly improved on by the OHIO Class submarine, the legacy OHIOs. 41 for Freedom was largely delivered in the 1960s. OHIOs were largely delivered in the 1980s. They were intended to be a 30 year platform, which meant that we would have been required to start recapitalizing them with deliveries in the 2010s, where we are right now.

Because of great design work at Naval Sea Systems Command, our engineering director was able to verify that the ships would be adequate to be extended another 12 years, from 30 out to 42 years, which is a tremendous accomplishment to do, an extension of that magnitude, and still be able to safely operate and certify those ships for continued at sea patrols.

In addition, due to a variety of reasons including arms treaty talks, we reduced the force from 18 SSBNs down to 14 SSBNs. That allowed, in essence, a further extension because we didn’t have to recapitalize the first four SSBNs. We converted those to SSGNs. We are now recapitalizing them by introduction of the Virginia Payload Module, but because they’re no longer SSBNs that allowed us to delay the OHIO Class recapitalization even further.

So with all of that, we will be delivering the OHIO Replacement SSBN Class, a force of 12 submarines, in the late 2020s and into the 2030s and early 2040s. The impact of this is that we can’t extend the OHIO any more. We cannot delay recapitalization any more. It is our obligation now to recapitalize this force to allow the nation to continue its reliance on SSBNs for the strategic deterrence mission.

It is possible that we are able to do this only because of the engineering advancements that Admiral Caldwell talked about, the life of the ship’s reactor core. That allows us to go from 14 OHIOs down to 12 OHIO Replacements. As Admiral Tofalo said, though, 12 is the number. You cannot say, can’t I just put more warheads on fewer submarines and accomplish the same thing? The answer to that is absolutely not.

The reasons would quickly get classified, but as Admiral Tofalo said, the survivability of the force, the ability to operate in two oceans, the ability to ensure that an adversary cannot reliably target your force, all of that relies on a dispersed strategic deterrence, and the numbers add up to 12 SSBNs.

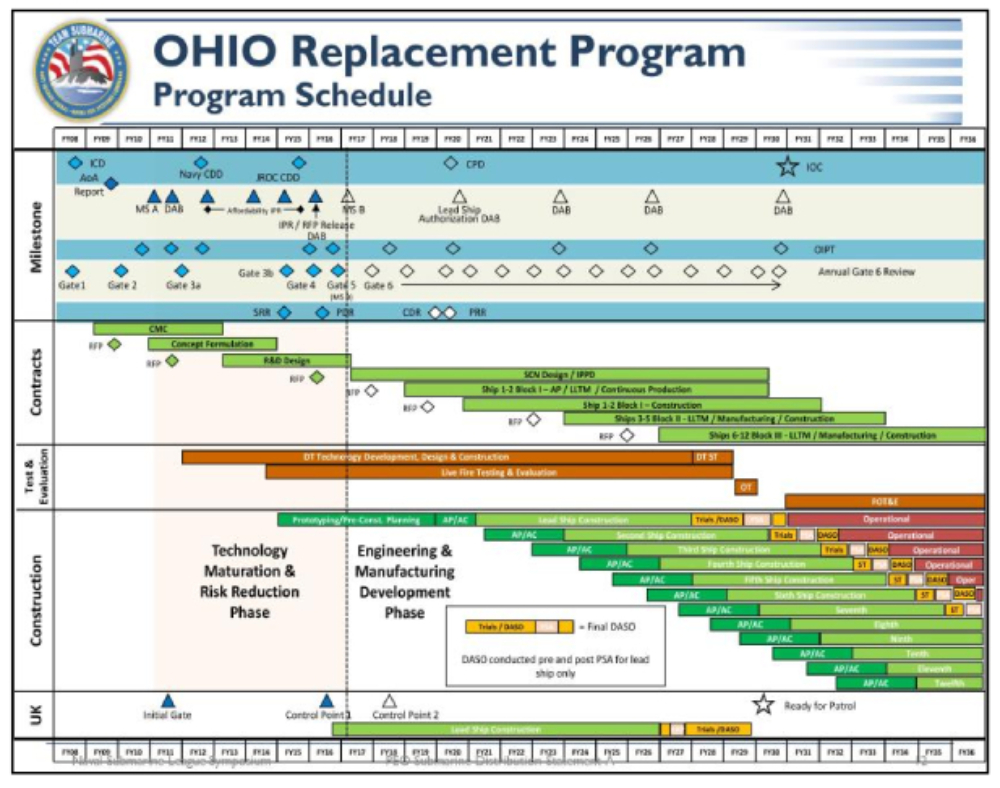

Now we were originally planned to start construction in 2019. We took a two-year slip to 2021 several years ago due to budgetary reasons. That took all of the margin out of the program. We have to deliver these submarines on time in order for that force of 12 submarines to be able to continue.

You will notice that there’s a period where we actually do go down to 10. That’s only possible because we’re not yet into the years where the OHIO Replacement will have their depot level maintenance availabilities, and we’re already beyond the years where the OHIO legacy class goes through its final depot maintenance availability. So we have an unbroken string of years there where we will have 10 operational submarines.

But normally it takes 12 to make 10 because two are either going into or coming out of depot-level maintenance. Even without the refueling overhaul, we still have to get the maintenance done. So 12 is the number and the number shall be 12.

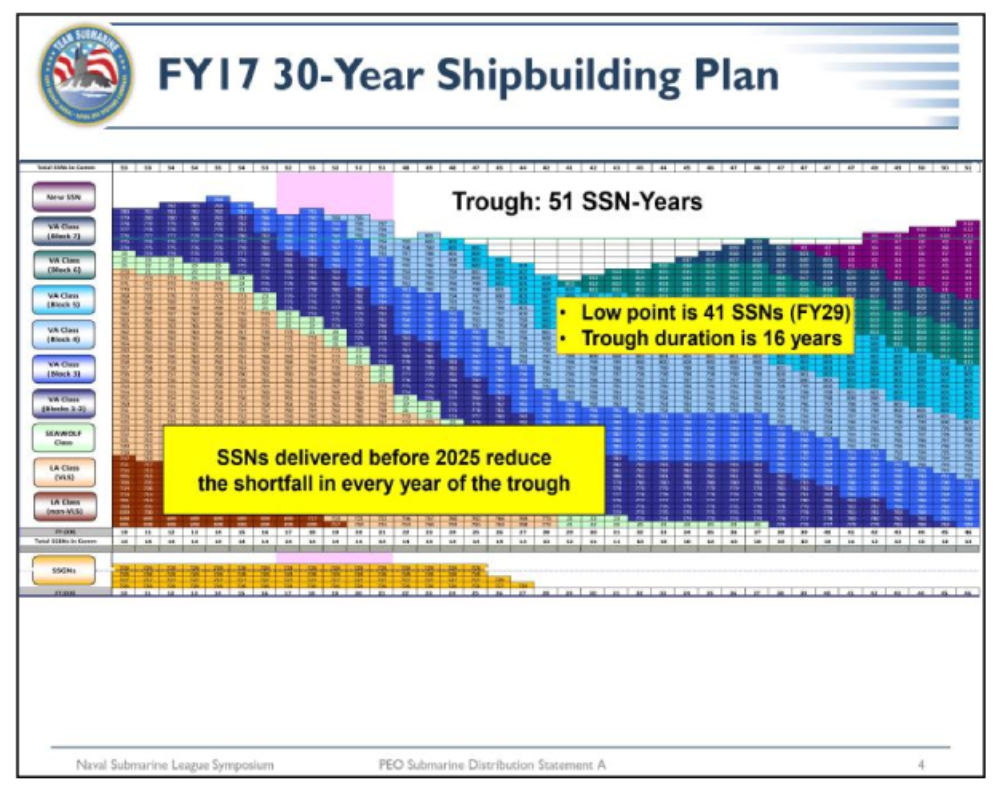

So that’s the SSBN environment. The SSN environment remains the same. We are still facing a trough where we go below the requirement of 48 SSNs. If you read the coverage of Congressional testimony earlier this year, you heard two of the Department of Defense’s combatant commanders, Admiral Harry Harris in the Pacific Command, and General Philip Breedlove in the European Command, an Air Force general, both say that their highest priority was additional attack submarine presence. We don’t have enough submarines right now to fulfill the requirements of the combatant commanders, and it gets worse.

As you see there, the trough, starting in about 2025, takes us down to a low of 41 SSNs before we begin to climb back out of it. This is the result of the high construction rate of LOS ANGELES class submarines during the ‘80s and the inevitable decommissioning of those same submarines years later. We have mitigation steps that we’re working on, but they cannot remove all of this impact.

The only thing that you can do to fill in that trough is build additional submarines. That’s why the first opportunity on the force structure chart of 2021, when we authorize the first OHIO Class Replacement submarine, is to take that year and put the second VIRGINIA back in and instead build three submarines in that year. A VIRGINIA Class submarine authorized in 2021 will deliver in 2025 or 2026, which is about when the trough starts.

So that one submarine will fill in one of those empty boxes every single year that that trough exists. In fact, it completely removes that four year extension off to the right where we briefly have 48 and then go back to 47. That part goes away with that one submarine because it is delivered at the beginning of the trough, an incredibly valuable submarine from the force structure perspective, and it’s an opportunity for us to achieve efficiencies in construction as well.

I’ll let you in on one of the worst kept secrets in the U.S. Navy. As you know, the Navy has been executing a force structure study. In testimony earlier this year Congress asked the CNO, Admiral Richardson, where he thought the new numbers would end up. In particular, one of the Congressmen asked him if he was willing to bet his paycheck on whether or not the numbers would go up. Admiral Richardson said yeah, I’d probably bet my paycheck that the numbers are going to go up.

Secretary Mabus gave an interview a couple of weeks ago and he was asked the same question. He said, yeah, I’d probably bet the CNO’s paycheck that the numbers are going to go up.

So I’ll just put my chips on the same bet. I think that the numbers are going to go up. I think that the Attack Submarine Force Structure numbers are going to go up. Obviously, until the Navy releases the study, nothing is definite. But the point is, this trough below 48 SSNs is not going to get better and in all likelihood it’s going to get worse.

So we have to do everything we can to execute our principle mitigation steps, which we defined years ago as delivering the VIRGINIAs earlier than we had been. The first one was about an 86 or 87-month construction span. We have gotten that down to the low point, on MISSISSIPPI, which was 62 months.

So we’ve taken a full two years out of the amount of time it takes to build the submarines. That gets each submarine to the Fleet two years earlier than it would have been had we remained static, which we were never going to do. But continuing to reduce that construction span as much as possible gets those ships there incrementally earlier.

Incremental life extension for selected 688-class submarines, the second mitigation step. Any time that we get about five years away from a planned decommissioning, we start to look at that submarine and say, okay, how much gas is left in the tank? Is the reactor adequate to continue operating in that ship beyond what we had originally planned? What about the material condition of the ship, the ballast tanks, the non-pressure hull, the internal tanks, the normal fuel oil tank, all of the things that require significant maintenance effort to maintain and certify that ship for continued operation?

And then we look at the actual deployment schedule. You say, okay, that one, she’s coming back 18 months before the end of her life, as currently planned. Well, if we can extend her for six months we could conceivably get an additional deployment out of that ship before we decommission her. So every ship, again, as it nears decommissioning, we go and do that math.

But again, the most that we can do is get one additional deployment out of that ship. That’s great from a presence standpoint. It helps us during peacetime, but it doesn’t mean that that ship will be available a year after that. And if that’s the time that we have to surge to protect our nation and engage in worldwide interests, then it’s not much help.

Then the final one, again a similar impact, selected extensions of deployments. We want to maintain deployments at six months, but there are times when the world conditions require that we extend a ship on deployment. Again, you look at the operating cycle of the ship and if we have to we do that.

So those were the three mitigation steps we defined when we first recognized the trough that was ahead of us: earlier delivery of VIRGINIA Class submarines, selected life extension of the 688 attack submarines, and selected extensions of deployments beyond six months. In doing so we have prepared ourselves to manage our way through the trough, but we haven’t even gotten into the meat of it yet. So it is, again, incredibly important. The only way you can really impact that white space and fill in those boxes is building additional submarines, and because of the timing, that second VIRGINIA in ‘21 is the most valuable.

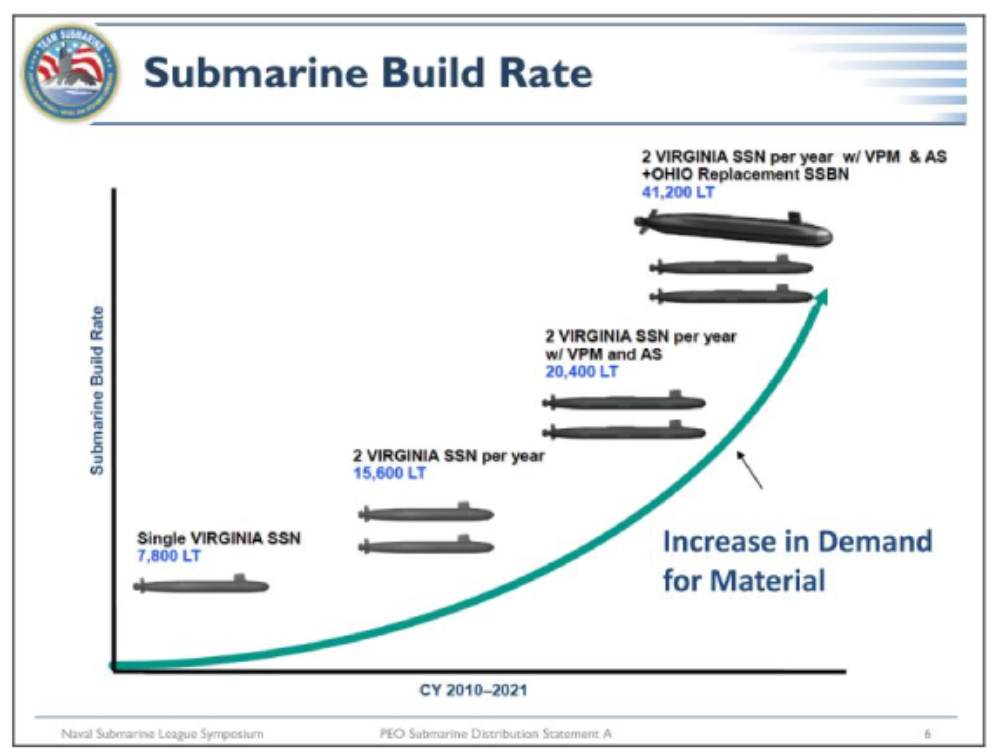

So to kind of put up a pictorial view graph, not to scale, not mathematically accurate, but if you just look at where we started in the early 2000s to where we’re headed in terms of shipbuilding, and the long tons of submarines that we are intending to produce every year, you can see that there is a significant amount of work facing our enterprise in the future. Again, that presents both challenges and opportunities. So given the environment that I’ve laid out and given the problem that you’re staring at right now, what are we doing about it?

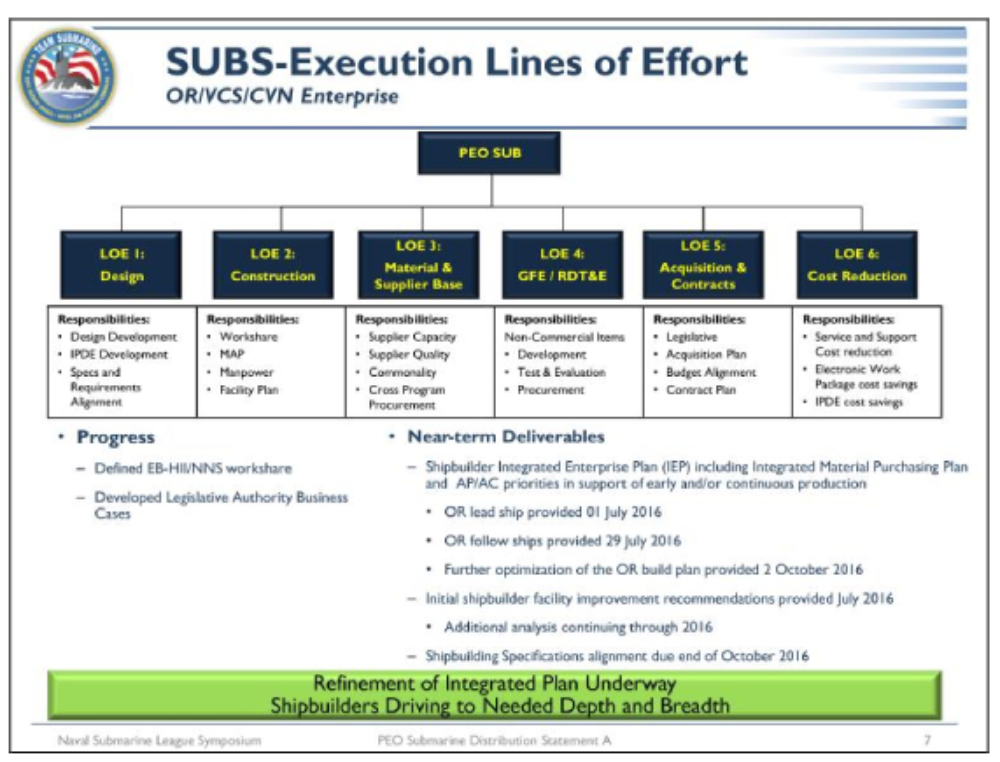

To confront both the challenges and opportunities, we have worked with our industry partners and our government partners to put together the Submarine Unified Build Strategy. Because the acronym is SUBS, it’s a good name. I will say that it’s not 100 percent accurate because it also includes a little bit of nuclear aircraft carrier impact, because that is again an opportunity.

So this is a management construct that we developed that defines fixed lines of effort. Those lines of effort are geared towards attacking the challenges and capitalizing on the opportunities. So let me spend a minute and walk through each one.

The first line of effort is design. We are embarking on we are actually well into a significant era of submarine design. The OHIO Replacement SSBN design, the Virginia Payload Module design, and the acoustic superiority design, all three of those efforts are well underway. Acoustic superiority is, in fact, nearing completion.

In design, we are using a fundamentally new design tool, as compared to what we used on the VIRGINIA Class back in the ‘90s. We’ve transitioned from CATIA, which is a 3D model product, to what we call the Integrated Product Development Environment, based on commercial products from Siemens NX team center. I don’t want to say modified, but adapted to the particular uses that we need, this design tool is foundational to our ability to design the ship on-time and achieve cost savings in the design stroke itself.

Like CATIA, it is a three dimensional model, but it is so much more because it seamlessly links all of the products you need to design the ship and then go build the ship. As we continue to fully complete the use of IPDE, we do expect significant cost returns from it and we are already beginning to see the improvement in the design effort on OHIO Replacement.

Line of effort Two is perhaps one of the biggest of the six because it’s construction. This involves the actual methodology and plans for ensuring that the companies are ready to build the submarines. So Electric Boat, at their sites both in Groton and Quonset Point; and then Newport News at their site in Newport News, Virginia; each have detailed plans for everything that you need to do to build the VIRGINIA Class submarine with VPM and acoustic superiority, and the OHIO Replacement at the same time.

So we’re talking about the facilities expansion that has to take place, a detailed plan for what buildings you have to build, what fixtures you have to design and procure, when all of that has to get built, how you reconfigure the infrastructure of your site in terms of power lines and everything else that goes into the building, moving roads, in the case of Quonset Point, to accommodate new buildings.

The manpower plans, where are you going to find the thousands of construction workers that you’re going to need to tackle this mountain of work? How are the communities and the academic institutions going to produce the quality of high school graduates or college graduates that you need so that you can train them to be the welder or the pipe fitter or the electrical engineer or the designer in order to do this work? Again, you can’t underestimate the expansion, if you think back to that curve, of the work that we are facing and the additional number of people that you’re going to need.

And then finally the spatial flow itself. How do the sections, the super modules of each submarine, move through those sequential sites in a manner that doesn’t conflict with the others, and ensures that all of the prerequisites come together to support that flow, so you can get to a final hull complete in either Groton or Newport News and delivered on time?

Line of effort Three is one of the most aggressive ones from the term of cost savings. It’s the material and supplier base. Again, we looked at the mountain of work facing us and said, we have to capitalize on this. We, the government, have to get the volume discount that should accrue by the combined purchasing of all the things you’re going to need for the two different classes of submarines, and here’s where the carrier comes in, because a lot of the components are similar or identical on the carrier when you get to the nuclear power plant and nuclear shipbuilding concerns.

In this line of effort, we perform targeted vendor analysis and cost comparison, and say okay, can we align the specifications for the OHIO Replacement submarine such that it matches up very well with the VIRGINIA Class submarine, such that when it’s time to buy 10 ship sets of a chill water pump for the VIRGINIA, we’re buying the exact same pumps for the OHIO Replacements that are building at the same time? And if that pump is used in a similar or identical capacity on the aircraft carrier, we can buy all of that at the same time. Again, that’s a volume discount price that we need to take advantage of.

In order to do that, we have to reinforce with our vendor base that this mountain of work is facing them as well and that they need to ensure that their quality, their cost and their capacity is ready to accomplish that. So this line of effort is going out and doing targeted analyses of the top 25 suppliers to the shipbuilders to make sure that they understand and are ready to execute the work, and that we can work with them to get the best price as we go forward.

I may not have mentioned, most of these lines of effort have participation from the shipbuilders as well as the government. It is a unified attack on the mountain of work ahead of us.

Line of effort Four is one of the ones which is government only, because it deals with government furnished equipment and the RDT&E necessary to do the technology development that the government supports. So these are things like the propulsor design. As we’ve talked about already, this class, the OHIO Replacement, will be in existence until the 2080s. In order to meet the stealth requirements over that long period of time, it has to be as quiet as possible. It’s a much bigger submarine than the VIRGINIA, so we can’t just scale the VIRGINIA propulsors up to the size necessary to propel the OHIO Replacement.

So we are designing a new propulsor. We have several designs that we will down-select in the next several years. But this line of effort is similarly important because we have to make sure—in this case, we’re supporting the shipbuilder. We have to make sure that the government furnished equipment gets to them on time and that it’s adequate to do the job.

This also includes the SWFTS systems, non propulsion electronic systems. Admiral Tofalo was talking about the sonar, the combat control, imaging, ESM. All of that, again, a direct pull from VIRGINIA. The same systems that will be provided to VIRGINIA we’ll be providing to OHIO Replacement at the time.

Line of effort Five deals with acquisition authorities in contracts. This again is an important aspect of what we’re doing and in order to do it we have to mesh very tightly both the VIRGINIA and the OHIO Replacement Program offices.

This line of effort puts together the business case analyses necessary to provide justification to our Congressional stakeholders to give us the authorities we need for a non-standard way of doing business when we procure these ships. So this includes several things, chiefly among them, one that we’re already working very hard and anticipate to be able to start executing next year, the continuous production of missile tubes.

So the 87-inch missile tube, 16 of which will go on the OHIO Replacement; we’re also buying 12 each for the UK Successor SSBN-class; and then 87-inch tubes form the four payload tubes in the Virginia Payload Module, as well as the two tubes in the bow on each Block III and beyond VIRGINIA.

That’s a significant amount of work for 87-inch tubes. What do we want to do? Well again, we want to get a volume discount for the amount of work that we’re going to be doing, but we also want to make sure that the ramp up for that work is smooth and gives you the best efficiency from the industrial base perspective.

If you only did it the year that each of the submarines was authorized, you would have some wild saw tooth swings because the first OHIO Replacement is in ‘21, then we take a two year gap, then there’s ‘24, then a one year gap, and then we finally get to one per year. So continuous production authority says, okay, we’re going to use an investment amount of money to start this work and we’re going to ramp it up and reach a stable base. Now we’ll actually be building some tubes ahead of when the submarine that they’re going to end up going on gets authorized, and that’s why we need Congressional authority to do it.

So we’re working very closely with our partners in Congress on this to ensure that we get the authority. We’re working within the Navy and OSD to ensure that we get the funding, because you do have to pull money earlier in the budget to do this. But it does two things.

Number one, again, it helps the industrial base tremendously, which allows us to get cost savings in the way we do it. And then it derisks the schedule, and that’s incredibly important because as we’ve discussed, the need of the OHIO Replacement to deliver on time and get out on patrol before the OHIOs decommission, is primary.

The final line of effort is cost reduction. This is similar to the 2 for 4 in ‘12 effort that we all remember so fondly. On the VIRGINIA Class when we needed to get to two per year we had to take 20 percent out of the cost of the ship to get to $2 billion per year for two ships a year (as measured in ‘05 dollars). This reinstitutes that effort the design for affordability or design for cost reduction, while we’re early in the design phase and can still maximize the advantage of the design opportunity to reduce construction costs.

So what has all this done for us, this Unified Build Strategy? We have successfully presented the business case for continuous production. That is in process, making its way through the approval chain, and I’m very confident that we’ll see that embedded in the program on a go-forward basis. We are continuing to work other initiatives: acceleration of significant components of the ship.

Again, the biggest problem that we have is there’s no margin between the decommissioning of OHIOs and the delivery of OHIO Replacement. Anyone who has been involved in a shipbuilding program knows that there will be unknowns that pop up and cause delays to the schedule. So my job is to try to buy margin back into that schedule so that when the inevitable unknown presents itself it’s not a fatal collision within the construction plan.

So to buy that margin back into the schedule we’re looking at targeted elements of the ship where we can accelerate the construction through the use of Advance Procurement funding or Advance Construction authority, to start those parts earlier and de- risk that schedule. That, again, requires taking money out of full funding down the road and pulling it earlier into Advance Procurement, Advance Construction authority. But it provides a significant benefit from schedule de-risking.

I also talked about that multi program material procurement, the ability to buy components for OHIO Replacement, VIRGINIA Class submarine, and even the CVN program. That is additionally one where we want to be able to combine the money into single purchase orders through the companies and provide the cost savings back to the government.

So those are the ones where we’re continuing to work and expect to be presenting those for approval over the next year or two. But the overall effort of the Unified Build Strategy has taken us significantly beyond where we were a year ago, in particular in terms of the construction readiness on the part of the team for building the OHIO Replacement while we continue to build VIRGINIAs.

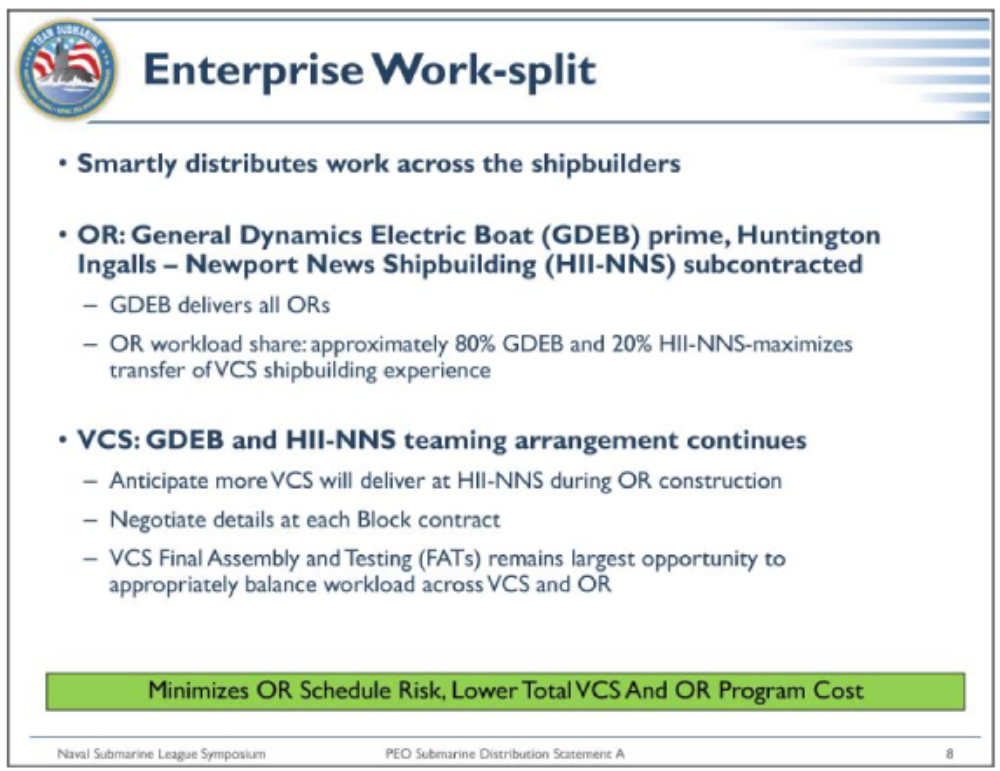

Some of the things we have determined and defined as a result of this work. We announced earlier this year, back in March, that we have determined that all of the OHIO Replacements will be delivered by Electric Boat. That is principally a result of the desire to minimize the amount of additional facilitization that would have to be done in order to deliver a ship of this magnitude.

So EB will deliver all the OHIO Replacements. The work share is going to be approximately 80 percent at EB and about 20 percent at Newport News. It’s actually a little bit more like 78-22, but all of that will be defined as we move forward and closer to a construction contract.

A teaming arrangement similar to what we have on VIRGINIA is anticipated to continue. Again, this will all be defined in the construction contract. But because this is a unified strategy, we are able to really maneuver levers on both classes to achieve a common good.

So given that EB will deliver all the OHIO Replacements and is doing a significant amount of the work on those, it’s inevitable that some of the VIRGINIA Class submarines will shift to Newport News to evenly spread the workload over the next several decades. The Final Assembly and Test the delivery of that submarine really is probably the lever that has the most impact on the overall work split and because of that we will negotiate each subsequent block VIRGINIA contract.

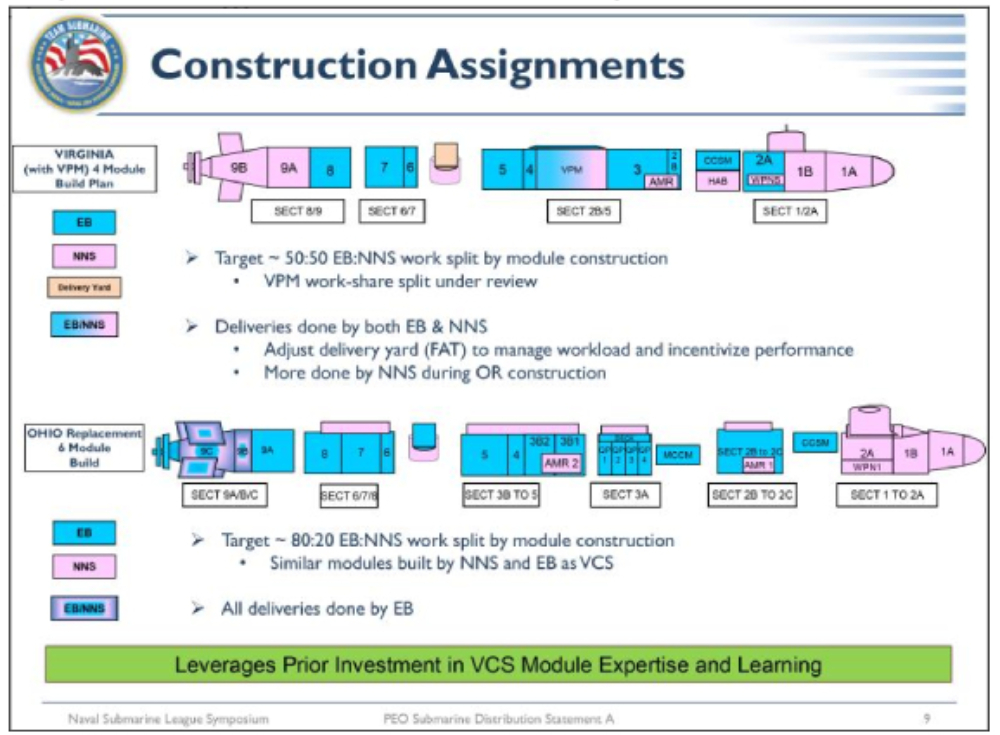

As we get more and more into the fully formed design of the ship, we are better defining exactly where the portions of the ship will be built. This shows the VIRGINIA Class submarine on the top and the OHIO Replacement on the bottom. As you can see, it’s not 100 percent identical, but we’re following the dictum of you do the similar work in the same place.

So Newport News is building the bows for each of the VIRGINIA Class submarines. We anticipate that they will build the bow for the OHIO Replacement. They build the sterns for the VIRGINIAS. They will also build most of the OHIO Replacement stern. There are some particular things in the OHIO Replacement stern that may make it better to be finished at EB as a result.

You can see the work split. But the key here, again, is relying on what has already become a center of excellence in one location and continuing to focus on that.

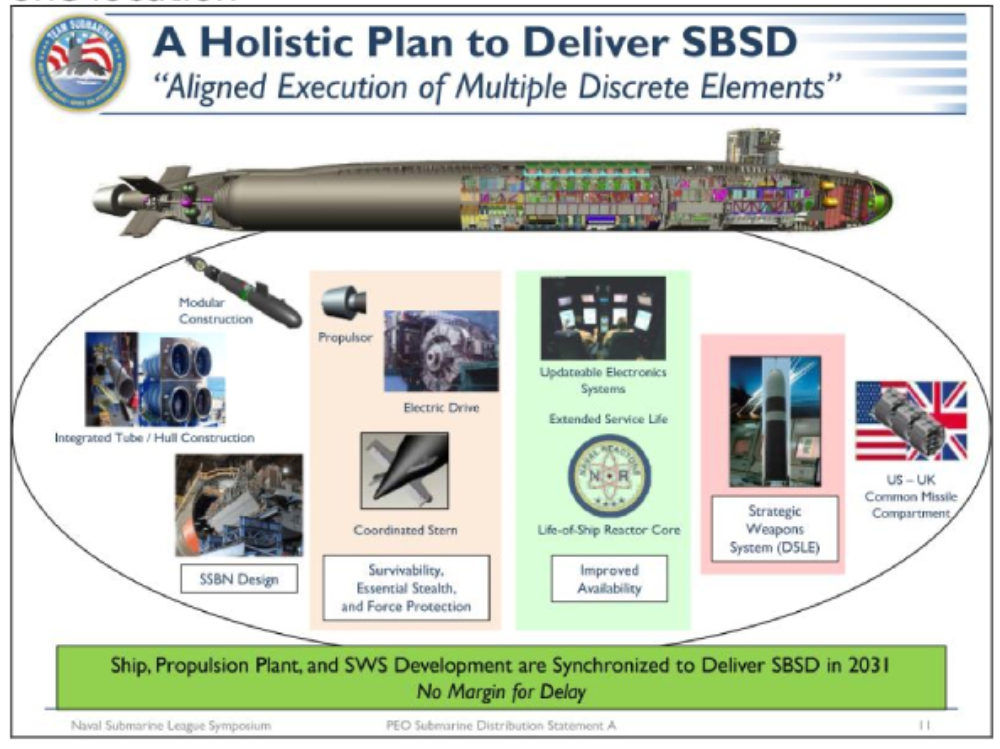

Some specifics on OHIO Replacement next. We’ve talked about this before. This is a holistic gathering together of several different streams. The design: pulling from VIRGINIA as much as possible; making technological advances where you need to and primarily that’s in order to maintain the stealthiness of the submarine out through the 2080s; the improved availability due to the life of the ship’s core; and then the reuse of the D5 with life extension weapons system. So you’re really pulling together efforts from the program office, from Naval Reactors, from the design community, from Strategic Systems Program, and then we throw in the cooperation with the UK just to keep things interesting.

So all of that together has to proceed down at the same pace and come to fruition in the fully designed submarine. So where are we?

This is a programmatic start and really I’ll only draw a couple of things to your attention. You see the Milestone B decision there just to the right of today’s dash line. As Admiral Caldwell said, early in November is when we anticipate that milestone. It is a meeting scheduled and run by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, so we are working with them to complete the milestone process.

You see below it, in the contracts line, that we’re also lining up for the SCN design. Here’s the analogy that I use to describe this, and it’s the four horsemen or the four horses. It’s not the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, because that would be a depressing analogy.

But this is like the old Western movies where we’re driving the stagecoach and have four horses pulling the stagecoach. In this case, they’re yoked together, but not very tightly. So here are the four horses.

Milestone B approval, that’s when OSD says yes you are an ACAT-1D program, the highest acquisition category, defense- level oversight, and we are giving you permission to proceed beyond Milestone B. The second horse is the contract award, in this case the contract is for the IPPD, the Integrated Product and Process Development contract to complete the design. The third horse is the transition from R&D funding for that design to SCN funding. And then the fourth horse is the funding itself.

So Milestone B, that’s nearly in hand. We’re going to go to the Defense Acquisition Board in early November and present the program to OSD and answer their questions and get approval. The contract award, we’re working very hard with our shipbuilding partners in getting to a contract award, because that is a negotiation. I’m not going to talk any more about that.

SCN funding, that’s wrapped up in the continuing resolution. An appropriations bill for this year would have included $773 million in SCN funding to do SCN-funded design, the detailed design that you need to build the submarine. Because we’re under a continuing resolution, I don’t have the SCN funding.

We have remained flexible and we’re continuing to support the design effort on things that we can spend R&D funding on, which I do have. I can do that until about the first of next year. But on 1 January I will have exhausted all remaining flexibility and the ability to use R&D funds to continue the design.

So if we don’t get an appropriations bill or a subsequent continuing resolution with an anomaly to fund SCN for the OHIO Replacement Program, we will be in a position where we will have to go redefine things in order to continue the design. It is unlikely for that to be approved and the alternative is that you slow down the design. If I slow down the design on this ship, then it is a greater than day for day delay once we do get funding and start it up again. So it is a perilous situation that I am hopeful will be resolved either in the next continuing resolution or with the passage of an appropriations bill.

One final thing on the Milestone B. I do want to clarify some- thing that Admiral Caldwell said on the cost of the SSBN. Our CDD requirement for the average cost of follow ships on the OHIO Replacement is a threshold of $5.6 billion and an objective of $4.9 billion.

So when he said that the cost will be around $5 billion, he was referring to the average follow ship cost, not the lead ship cost. Once OSD approves the Milestone B and issues the actual cost projection of the ship, I am very confident that we will be closer to that $4.9 billion number than we will to the $5.6 billion number. So that’s a good news story. Those were cost targets that were set years ago. We’re going to come into Milestone B and explain why we feel that we’re between the threshold and objective.

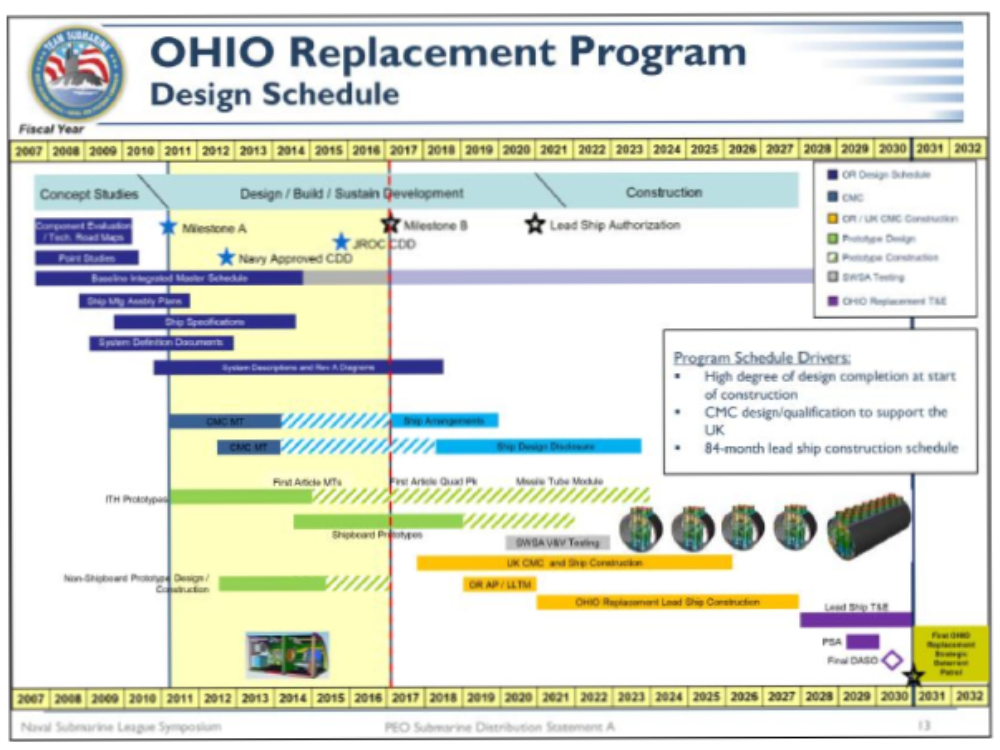

So in the need to get the ships designed and built on time, one of the ways that we’re doing this is through an aggressive prototyping scheme. The way to read this chart is that the solid colors are design stroke, and then the hash colors are prototyping. So where you see the quad packs, those four sections of the Common Missile Compartment, each of them with four tubes, all of the efforts leading up to that lead to the ability to build those on time.

As Admiral Tofalo said, we are already building pieces of this ship. It’s through R&D funding of prototype efforts that those prototype articles will be consumed in the first ship. So we’re already doing the integrated tube and hull pieces for the missile tubes. The missile tube vendors are already building the missile tubes and those will be combined into the first missile tube module and then the Common Missile Compartment.

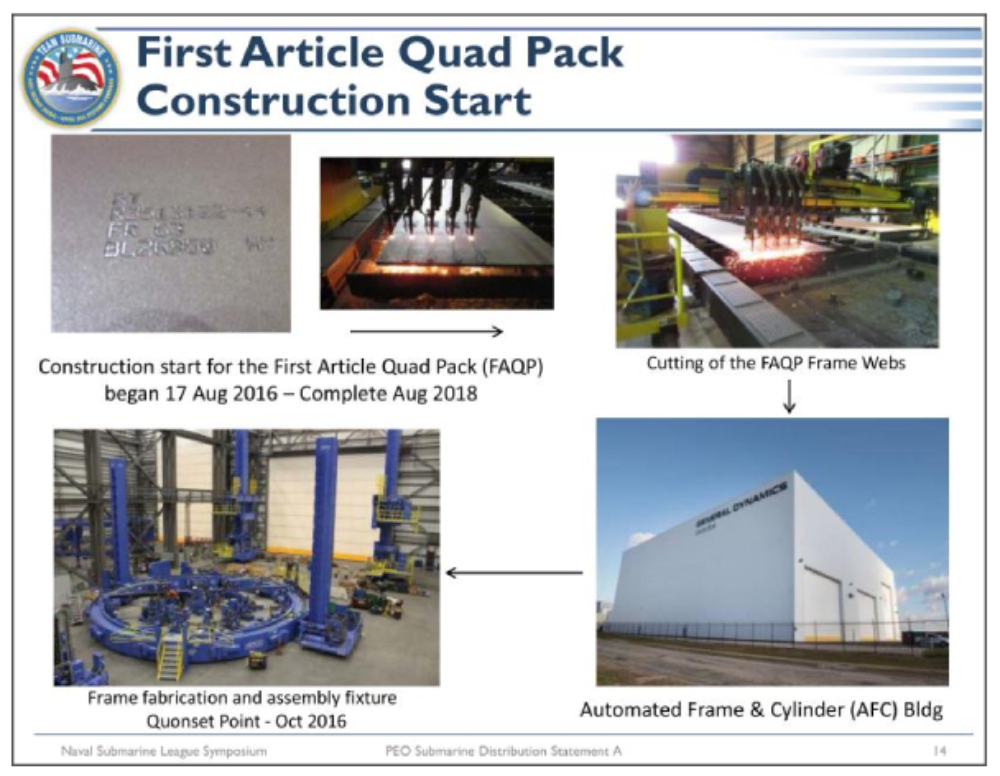

These are actual pictures from Quonset Point of the cutting of the first steel for the first article quad pack. Those are the frame webs in the upper right hand corner. They get sliced into long, rectangular pieces and then bent in the lower left corner, into a circular shape for welding against the hull surface itself. Again, that’s one of the facilities that was long in that plan for facilitization and moving into it.

Let’s talk about VIRGINIA. We’ll go through this pretty quickly. I know I’m running short on time. But the VIRGINIA Class, again, a tremendous success story.

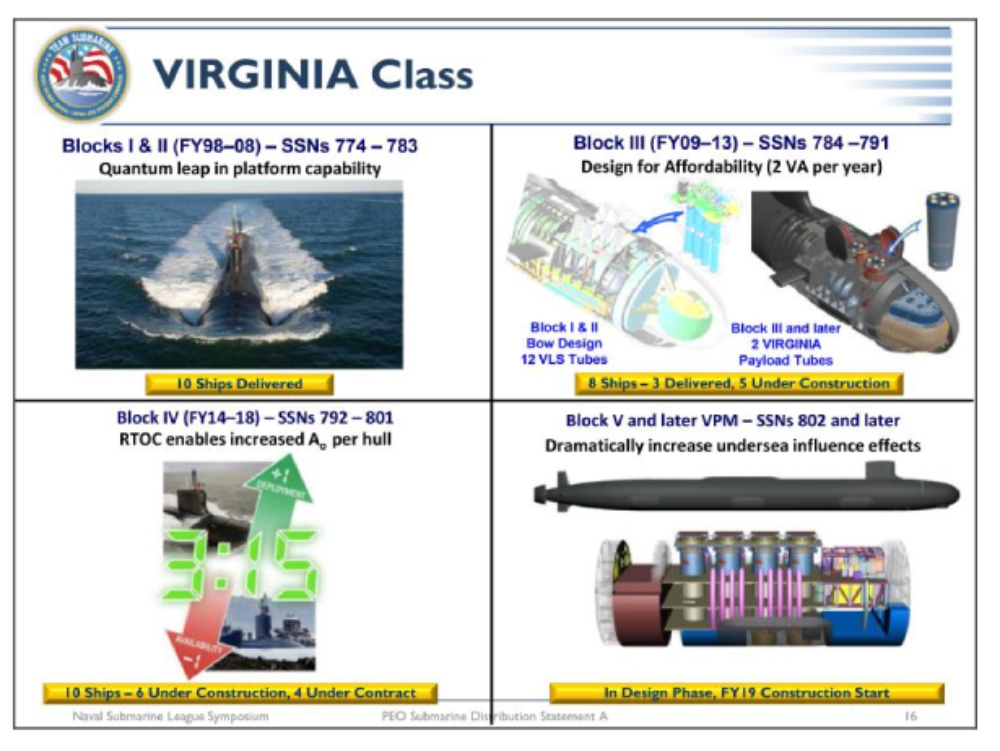

If you look at the focus on the first four blocks, blocks I and II together, we’re figuring out how to build the ship and getting it down to a reasonable span in time; block III was the design for affordability, the two for four in ‘12 that redesigned the bow of the ship, put in the large aperture bow array replacing the sonar sphere, and the 2 Virginia Payload tubes instead of the 12 missile tubes. Block IV was focused on reduction of total ownership cost. The design for that is complete.

In the submarines that we are building in the next couple of years you will get the full effects of that, which is fewer depot level availabilities and an additional deployment over its life. And then block V and later, the Virginia Payload Module and increased undersea influence effects, so that ability to make sure the submarine is relevant through the rest of its life.

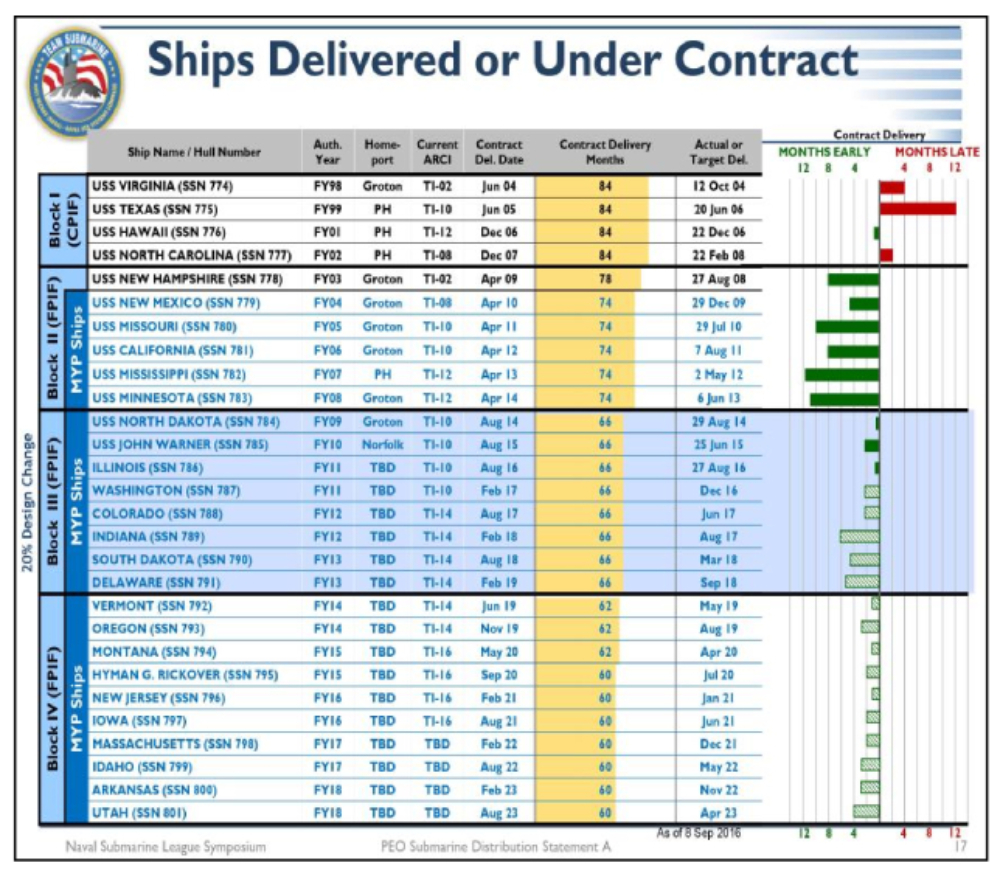

So where are we on this? If you look at this chart and you look at the color bars on the signpost on the right, on early ships those long bars were overruns in construction schedule. Starting with the fifth ship every ship since then has been delivered early to contract schedule. If you look at the block two, they’re as much as 12 months early.

Then you look at the block three and they’re not as early. But that’s actually a good news story because if you look over two columns to the left, the contract delivery span was reduced from 74 months down to 66 months. So we’re challenging ourselves and the shipbuilders to do a better job, and then holding them to that in the contract.

If you look at that with a little more granularity and go, okay, 784 and 786 just barely ahead of 785. So what was wrong with 84 and 86? The answer is nothing.

What was great about 785 is the question. 785, the USS John Warner, is a phenomenal ship. Not only did she deliver early, but then we turned around and did the shortest PSA in history on her and got her out to the fleet in a phenomenal fashion.

Some of this is just the vagaries of shipbuilding. Again, you don’t know what unknown is going to present itself and cause you trouble in the delivery stroke. With 785 everything went right. No unknown popped up and bit us.

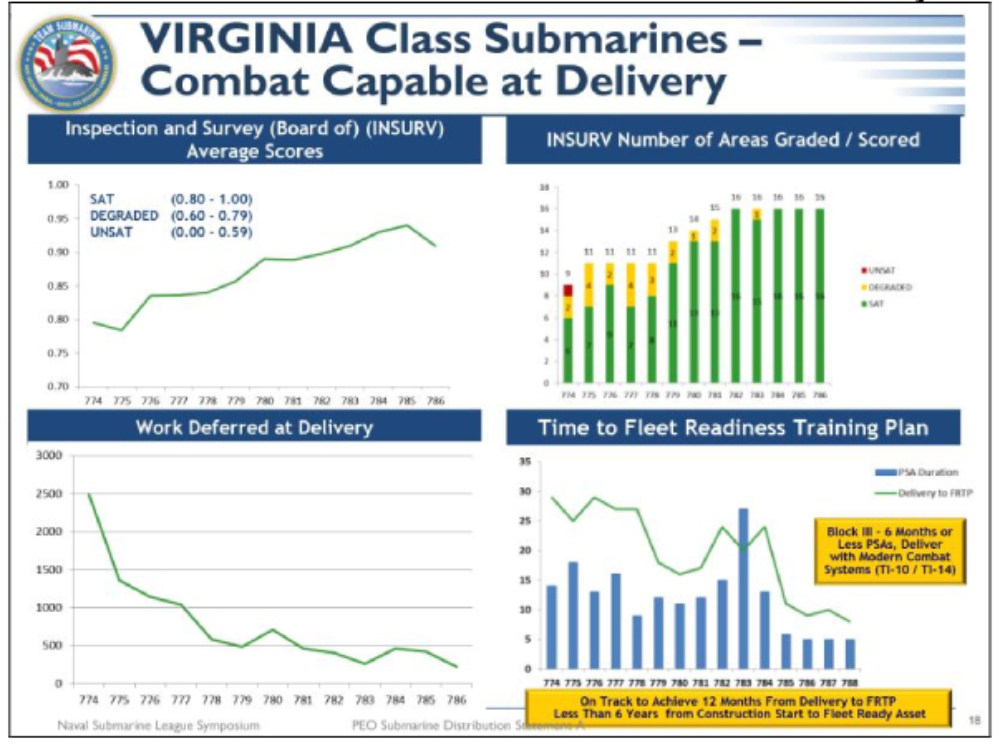

There are other metrics that we use to ensure that the quality is continuing to improve. The INSURV Board, Board of Inspection and Survey, this is the Navy’s independent organization that goes out and makes sure that we got what we paid for when we buy a ship. If you look at that line, it has continually increased upward to where it’s in the .9, the .95, area, which is a phenomenal performance on an INSURV.

INSURV is just a snapshot, one day in the life of a submarine. You’re going to have something break. But as you can see, we’ve had fewer and fewer things break. Again, it’s not a dig on 786. Really it’s what a phenomenal ship 785 was. I expect it will oscillate in the 9.0 to 9.5 range going down the road.

In the upper right, INSURV Number of Areas Graded and Scored. We’ve been all green on the last three ships and four out of the last five. These are the critical operational abilities that are tested by the INSURV Board. And again, to have all green on that many ships in a row is phenomenal.

The lower left hand corner, work deferred at delivery. These are the small things that you just couldn’t get done and it wasn’t worth holding up the ship from sea trials to finish. But again, a phenomenal improvement over the years in the number of things that we had to defer past delivery.

Then in the lower right, time to the fleet. This combines both the construction span and the PSA. As we have gotten into the block three where the hotel services to provide the SWFTS are all embedded in the ship already, we don’t have to do a long PSA to upgrade those. We are continuing to see improvement in the time that we provide those to the ship or provide those ships to the fleet.

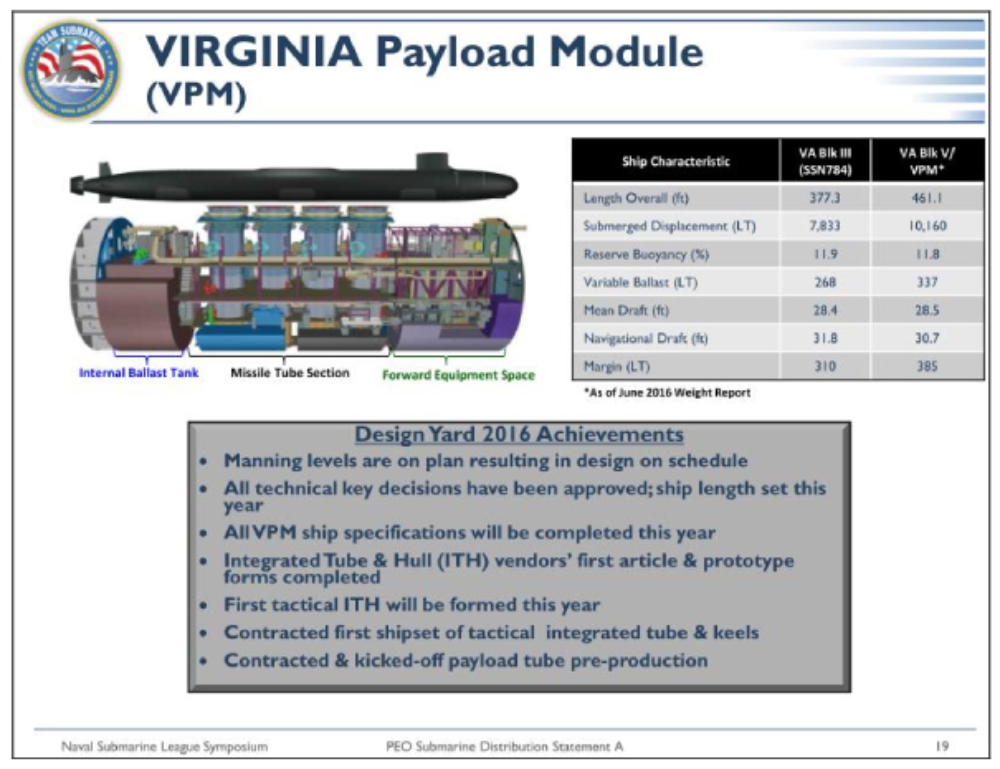

Virginia Payload Module, again very well in hand on the design here, proceeding very well. We will finish all of the VPM ship specifications this year. There’s really only one left and it may actually be done this week, depending on whether we get the final approval or not.

We have set the ship’s length, the module, the additional VPM module, 83 feet, nine inches and three quarters. That’s how much additional length we’re putting in. This is a stroke that has gone very well.

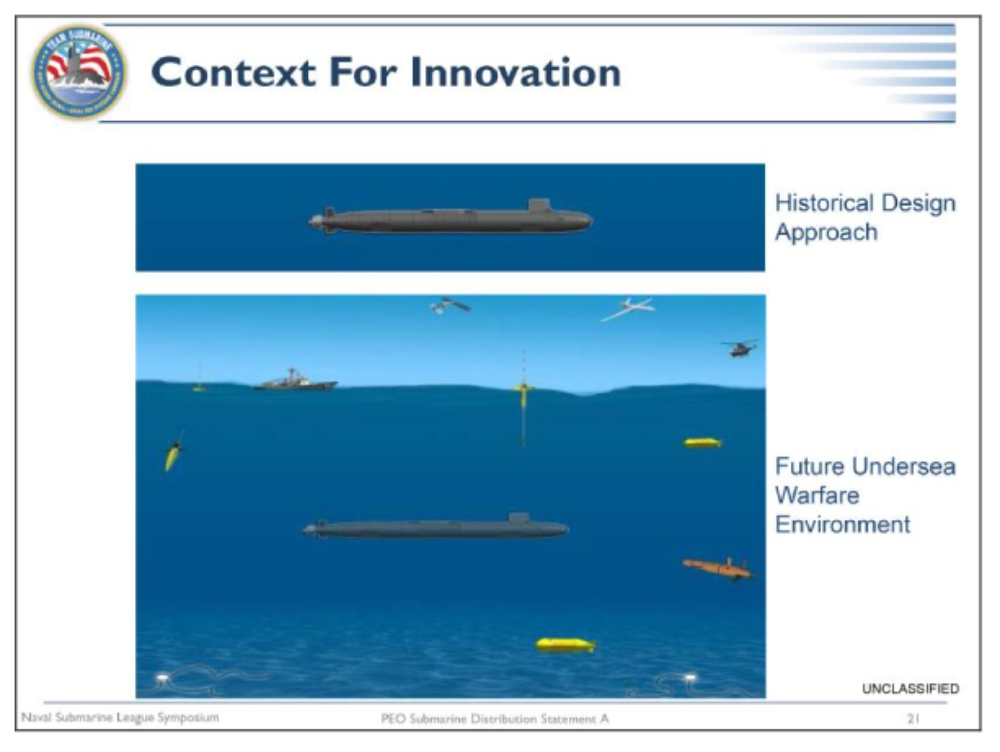

Let me close with just a few remarks about SSN(X). Admiral Caldwell talked about the need to aggressively pursue this and the work that the Future Capabilities Group is doing to set the environment. The historical design approach for an attack submarine before now has always been okay, what are the missions that it has to perform? How do you wrap that up in a submarine package? And then, let’s go build it.

We really have to think about this one differently. Several speakers have already talked about it and it’s a continuing topic of conversation. But this submarine, more than any before, has to be plugged into the environment in the undersea domain.

We have to have the ability to work with unmanned undersea vehicles and unmanned undersea systems: for example, the FDECO, the Forward-Deployed Energy and Communications Outpost. That’s a node on the bottom of the sea floor that is connected back to a power source so that a UUV can go plug in there and charge, communicate, and operate without over-watch. But someone has got to get that UUV there and someone has got to be able to continue to support the systems.

So in this design effort what we’re doing right now is working hard to number one, make sure that we have the right people and design tools ready to do this design. Then we’re using those people to explore the opportunities and define the area where we want to be able to focus on in the design of the ship. And what that will lead us to is an analysis of alternatives.

Really, we don’t start doing that analysis of alternatives until we get into the early- to mid-’20s, so we’re still about eight years away from that and working hard now to do the studies that will inform those AoAs. So we’ve talked in the last couple of months and there’s been some discussion about this, we may not do an SSN(X). We may build an eighth block of VIRGINIAs. That is always an option, but I don’t want anyone to think that we aren’t aggressively approaching the SSN(X) because the need for this type platform is significant.

Now, when will it actually be to the fleet? Well, as you saw from the shipbuilding profile, we’re talking about authorizing it in 2034, so it’s really about 10 years later after you build the ship, take it through PSA, take it through the initial operational test and evaluation, before you get it operating in the fleet. So we’re looking 30 years down the road and trying to anticipate what we’re going to want to do with this ship then.

I go back to the two things that I’ve always said that SSN needs to be focused on, in addition to all the other things you focus on in a new submarine: first, the ability to seamlessly integrate, deploy and employ unmanned vehicles. We have for years used any available interface on the submarine to get a UUV off the ship, whether it’s torpedo tubes, three-inch launcher or trash disposal unit. We have to get beyond that. There has to be a better way to design this submarine from the ground up to seamlessly employ UUVs.

I’m talking transformational stuff. I testified before Congress earlier this year and I said, you know, it’s like the Remora, that little sucker fish that attaches itself to the shark or the whale as it goes along. Maybe that’s the answer. Maybe there’s some way to figure that out.

But that’s the kind of forward looking thinking that Admiral Caldwell was talking about, casting the net wide, going out to industry, to small business, to academia, to our research partners at ONR and the UARCs and the warfare centers, and finding those really weird ideas that everybody says, that will never happen. Yeah, but maybe there’s a part of it that can and maybe that part you can pair with a part from something over here, and before you know it you have something useful. So that seamless employment of UUVs is the first one.

The second one is, all the work that we’re putting into OHIO Replacement to make it stealthy out into the 2080s is significant and it’s hard and it’s challenging, but at some point we have to go beyond that too. It may be time to go beyond that rotating thing at the back of the ship, the propeller or propulsor, to get it through the water. So that, again, type of transformational propulsion system is something that we have to look at, whether it’s the caterpillar drive from “Hunt for Red October,” or it’s biomimicry, we don’t know.

But again, we have to cast that net wide and figure out what is going to protect our submarines well beyond the 2080s and how do we get that into the SSN(X). So although continuing to build VIRGINIA is always an option, we are aggressively pursuing the far-reaching concepts that will allow us to do an analysis of alternatives in the early- to mid-’20s with an eye towards building SSN(X) starting in 2034. With that, I’m done. I don’t know if we have time for questions or not.