DR. DAVID ROSENBERG: Good afternoon and welcome to the Sixteenth Naval Submarine League-Naval Historical Foundation Submarine History Seminar. I am a longtime member of both the Submarine League and the Foundation. I do recommend membership to both. May I have the first slide, please? We are here to talk about atomic submarines. We are here to talk about U.S. submarines trailing Russian submarines.

But the key issue is we’re here to talk about atomic sub-marines because the fact is that only atomic submarines can trail other atomic submarines The interesting point about all of this, however, is, just like the movie and the book are based on some aspects of historical fact, much of that fact still remains classified.

So, for the submariners in the audience and any others, including NCIS agents, I want to assure you that everything that is on the screen, at least, and what we are going to be saying, has, in fact, been cleared through the submarine force and through the Office of the Secretary of Defense. With that, let’s get started.

Next slide, please. I think any of you who have any familiarity with the history of nuclear submarines know about Hyman G. Rickover, the engineering duty only admiral who, starting as a captain, literally created the atomic submarine.

But what is often forgotten is the operational aspect of it, in part because it’s so classified.

The plan for atomic submarine was built on the experience the World War II experience of submarines. But some of the lessons, some of the leadership, were provided by folks who weren’t. This is a quote from Admiral Arleigh Burke, Chief of Naval Operations for three terms, six years, from 1955 to 1961. It was Burke who made the decision in late 1955 to make all future submarines nuclear powered and to begin the Polaris program that created the ballistic missile submarines.

Burke, in January of 1959, decided to have a one on four talk with the first skippers of U.S. nuclear submarines, namely in particular at top: Captain Dennis Wilkinson, (this [picture] was taken in 1955), the first skipper of Nautilus; Commander William Anderson, who was the cur- rent skipper of Nautilus; Captain Dick Laning, who was the skipper of Seawolf, the second [nuclear] submarine; and Commander Jim Calvert, skipper of USS Skate.

Nautilus and Skate, [during] the previous summer, had [sailed under the ice to] the North Pole. They received great news coverage. Nautilus got a ticker tape parade when she came back to New York.

But what you had here was a meeting between Burke and these four skippers talking about the future. They talked about a lot of issues, engineering questions, how many [different] classes [of submarines needed to be built], whether the Navy were moving too fast, and some interesting points about [Rear Admiral] Rickover. At the end, Commander Calvert raised the question. He said, sir, do you have any charge for us? What should we be doing?

This is what [Burke] said, develop our knowledge of the areas around Russia, [and] follow the Russian submarines so that “we know what we have got.” He noted “if they know that we are following them, it doesn’t matter” but that wasn’t quite true and then develop anti-submarine training for our own forces to know how to deal with these submarines. Next slide.

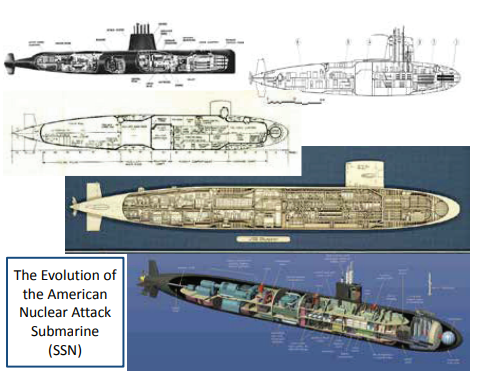

What we saw was, during the period between the 1950s and the 1980s when the book and the movie “The Hunt for Red October” take place, the American submarine force evolved.

This is not a lecture on the evolution of American submarines, [but this slide is designed] to emphasize two points. The first point at the top is Nautilus, the Skate class was somewhat smaller and different but the key point on Nautilus is the nuclear power reactor.

This is the Skipjack. The Skipjack-class, you can tell, this is a totally different, revolutionary, hull form based on the hull form of the USS Al-bacore, an experimental [conventionally-powered] submarine.

And then what you have is the next three classes of American nuclear submarines.

This is the Permit or Thresher class, followed by the Sturgeon-class, and then finally the Los Angeles class. The Los Angeles-class, in the form of the USS Dallas in the movie and in the book, is the boat that trailed Red October.

The key thing I want to point out to you is this, the sonar dome in the bow. It is that capability, the ability to use sound to track passively the acoustic emissions of submarines that makes trailing possible. That is what is absolutely critical to understanding the broad technical aspects of all this. Next slide.

The problem is that, looking around the audience I don’t think this is an issue I don’t see that many millennials here but for those who may have forgotten, we had a formidable enemy in the Cold War. The Soviet Union built a great many atomic submarines. They surprised us with the speed in which they built them. They surprised us in many ways with the quality in which they built them.

Along the top row of this slide are the first nuclear attack submarine,

the first guided missile submarine, an Echo, which we will hear about shortly, and the first ballistic missile submarine, which this is essentially the same model, if you will, the same class as the K-19 for those who saw that movie about K-19, the widow-maker with Harrison Ford.

Then we have advanced nuclear submarines, Victor I and Victor III, and a new guided missile class submarine, the Charlie. And then finally, ballistic missile submarines that were utterly critical to the Soviet Union in terms of developing its nuclear strategy; initially Yankee-class submarines and the Deltas, a Delta III here, and the Typhoon.

The thing to remember, is this. The Russians built a lot of them. In 1982, according to the declassified National Intelligence Estimate on the Soviet Navy, the Soviet Union had a grand total of 363 submarines, of which they had 85 ballistic missile submarines. Over 60 of them were nuclear powered. They had 64 guided missile submarines, over 50 of them were nuclear powered. And then they had 214 attack submarines, more than two-thirds of those were nuclear powered.

This is a formidable navy. It’s something to really worry about. So, the question is, how did we balance against them? Next slide.

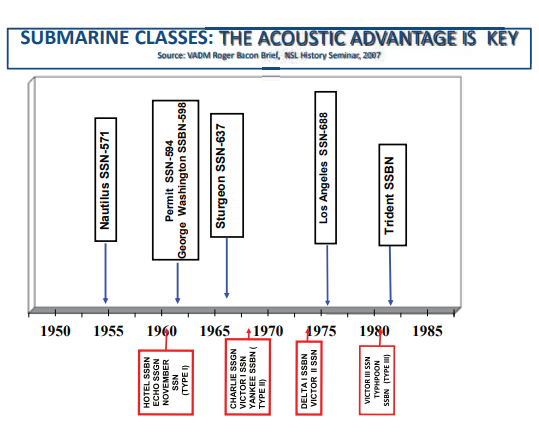

This comes from a slide from [Vice] Admiral Roger Bacon at an earlier submarine history seminar. It shows the evolution of the building and deployment of submarines [in the U.S. and USSR]: the first classes, the Type I, the Type II and the Type III nuclear submarines, when they came in.

While we can’t really show you acoustic advantage although the Navy did declassify some stuff on this in the 1990s it is acoustic advantage [that mattered]. It is the fact that we could hear them, and they could not hear us that made it possible to do the kind of trail that is written about and then shown in the book and the movie. Next slide.

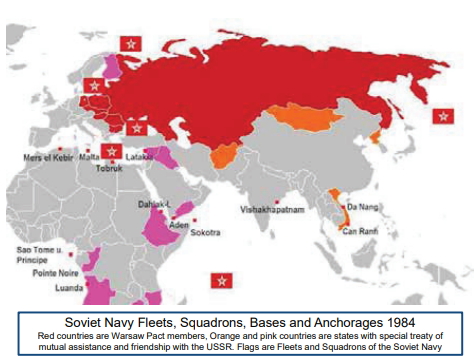

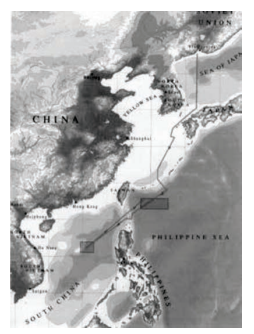

Just to remind you again of the formidable nature of that threat, this is a wonderful [map] showing the [dimensions of the Soviet naval threat in the 1980s]. There are the four Soviet Fleets: the Northern Fleet, the Baltic Fleet, the Black Sea Fleet, and the Pacific Fleet. [In addition], the Russians had the Fifth Escadre in the Mediterranean and the Ninth Escadre in the vicinity of Socotra Island in the Indian Ocean.

This was a global navy. It was a navy that worried us. The question is, how do we keep tabs on that navy? We had the 7th Fleet in the Pa- cific, the 6th Fleet in the Mediterranean, and the 2nd Fleet in the North

Atlantic. But the question was, how do you keep tabs on submarines? Next slide.

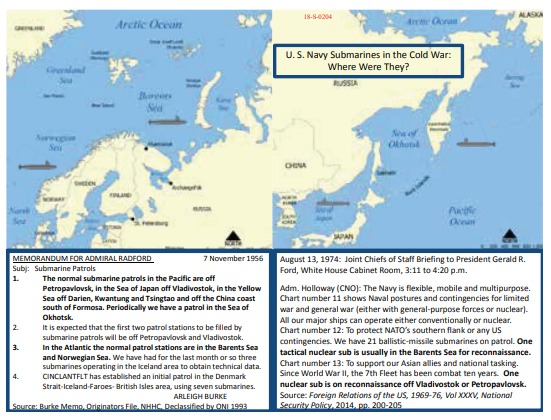

U.S. submarines, we can say this officially, at least through 1974 but one can in fact think a little bit further ahead given a line in the movie I will note we had submarines in the Barents Sea. We had submarines in the Norwegian Sea. We had submarines off Petropavlovsk and the Kola Peninsula. And we had submarines in the Sea of Japan off Vladivostok.

For those who might worry whether I’m giving anything secret away, that’s why there are these little comments down here. These are fully declassified statements of where American submarines were starting in ‘56 and continuing in the briefing to President Ford after President

Nixon resigned. U. S. submarines were there to keep tabs on the enemy, and this was a point of concern. Next slide.

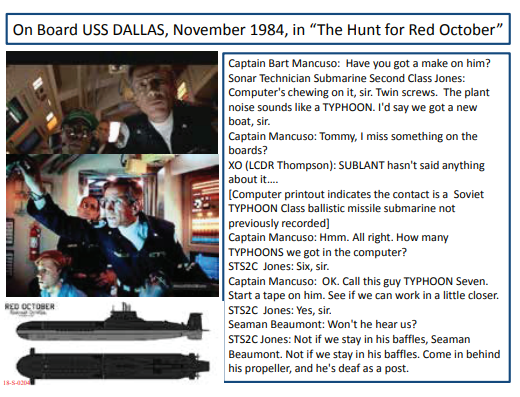

This is my favorite quote from the movie. Scott Glenn, playing Bart Mancuso, is talking to sonar technician second class Jones, and asking about this new contact and how to follow it. He replies it sounds like a Typhoon, [but the Dallas had received no previous] word on it.

You may recall in the movie that it is noted that USS Dallas is 100 miles off the Polyarny Inlet. The previous slide explains why Dallas was there. But the question is, what are we doing? And [what Captain Mancuso says we are going] to do is we’re going to start a tape on this new submarine and we’re going to try to work in a little closer.

This is the way we kept tabs on enemy submarines. Mancuso has this submarine designated Typhoon 7 (in reality there were only six Typhoons).

Typhoon 7, the Red October is a ballistic missile submarine. Next slide.

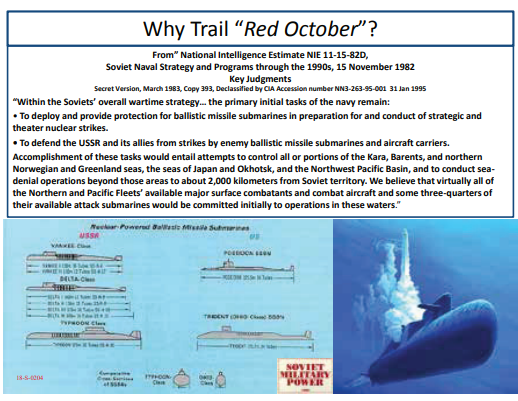

Why are ballistic missile submarines important? The declassified National Intelligence Estimate on the Soviet navy from 1982 emphasizes one key point. In Soviet wartime strategy the primary initial task for the navy remains to deploy and provide protection for ballistic missile submarines in preparation for and conduct of strategic and theater nuclear strikes.

[As this slide indicates,] the Russians had a good many [different classes of nuclear powered ballistic missile] submarines.

We only had two classes of nuclear [powered ballistic missile] submarines at the time. [The number of classes and the number of submarines in each class shows the importance of their SSBNs and] the role [that their] defense played in the defense of the Soviet Union and Soviet naval strategy.

That’s why you wanted to trail Red October. One key point, though, with respect to the Delta and the Typhoon SSBNs: there are lines in the movie that the threat from the Red October was that it could come over here [across the Atlantic] to shower us with nuclear missiles.

That’s what the U.S. feared Captain Ramius was going to do. No, folks, that’s the one thing that was a bit of a Hollywood embellishment to make the movie more dramatic. The fact is that the Deltas and the Typhoons couldfire from home waters; [they could shoot] 4,000-mile missiles at the United States.

That’s a key point. Next slide, please.

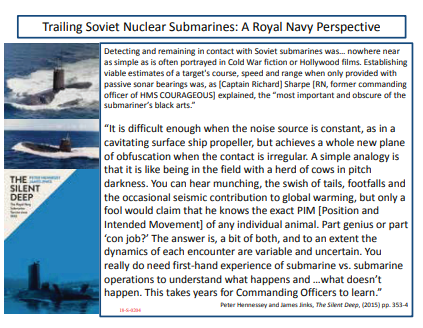

So, what was it like to trail [a nuclear submarine]? One of the things we [found as we worked on an introduction to this seminar is that the U.S. Navy has] not declassified any American comments on what it was like to trail a Russian submarine. [Fortunately,] the British have published a book called The Silent Deep, [by Peter Hennessey and James Jinks]. I recommend it to you, although it’s 800 pages.

It could be used as a door stop. Do not read it in bed as it could crush your chest if you fall asleep and it falls over [on you]. It is a marvelous book, however. It tells you wonderful things about British submarines, and along the way it tells you a lot of good things about American submarines. I refer you to this comment from Captain Richard Sharpe, later the editor of Jane’s Fighting Ships, who in fact talks about how difficult [trailing] is.

I love this line in particular, a simple analogy [for] trailing was that “it is like being in the field with a herd of cows in pitch darkness. You can hear munching, the swish of tails, footfalls and the occasional seismic contribution to global warming, but only a fool would claim to know the exact position and intended movement of any individual animal. Part genius or part ‘con job?’ The answer [is, a bit of both, and] to an extent the dynamics of each encounter are variable and uncertain. You really do need first-hand experience of submarine vs. submarine operations to

understand what happens and …what doesn’t happen. This takes years

for Commanding Officers to learn. Next slide, last one.

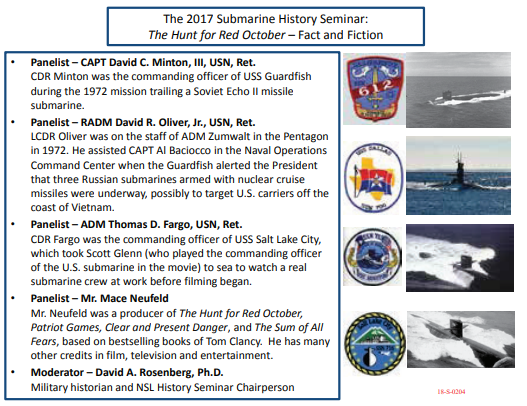

We are fortunate today that we do have three former commanding officers who, in fact, did know how to do things like this. In particular, Captain Dave Minton, who will be talking next about the trail he undertook on USS Guardfish of a Soviet Echo II Class submarine in the Pacific in 1972.

He will be followed by Rear Admiral Dave Oliver talking about what he saw in Washington of that trail. Dave commanded USS Plunger. And then finally [Admiral] Tom Fargo will be talking about his experience [as captain of USS Salt Lake City] taking aboard the cast of The Hunt for Red October.

Finally, we’re delighted to have Mace Neufeld, who produced the movie and a number of the other Tom Clancy and Jack Ryan movies. He will provide his perspective on the story. So, with that, I’d like to turn to Dave Minton. Go ahead, sir.

CAPT. DAVID MINTON: I want to talk to you about a trail that started in Vladivostok, way up north. The trail extended for 6,100-plus miles, 28 days in trail. It was an exciting event, there was no question about it.

It all started on 8 May when Nixon announced the mining of Haiphong and other North Vietnamese ports. As a result of that, there was a message that I received onboard Guardfish, and I was up along and close to Vladivostok along the Tubin River, Cape Codelang, which separated the Soviet Inland Sea and the open ocean. I was right along the channel where normally all Russian commerce came, military and civilian, in and out of that channel.

The message said, be aware they might respond to this. I was sitting there just waiting to see what was happening. There wasn’t anything going on. I was actually having dinner in the wardroom and I got a call from the officer of the deck. He said, there’s a noise level we picked up coming out of the northeast headed out from Vladivostok. My answer to that was, when you have him visually give me a call.

So, I got a call, and I went up and looked out of the periscope. I could see both port and starboard running lights of this vessel. Although it was designated as being some type of patrol craft, I knew right away it was a submarine because in fact I had spent a lot of time around Russian submarines and the starboard side light on Russian submarines was an off color of green, a dead giveaway.

So, I called the tracking party away, and this submarine in the growing darkness passed me. I could see each one of his launch cavities and could identify him as an Echo II class submarine.

This was the beginning of an extensive period of time at sea and in trail, and I’d like to jump forward in time. In 1999 the Naval Submarine League and Sonalysts developed a videotape, Century of Silent Service

many of you have seen it and a coffee table book United States Submarines. To have that book work, they had all sorts of information from earlier days, from the beginning of the submarine force up through World War II, all declassified. When it came to the Cold War there was nothing available.

So, in their infinite wisdom, they declassified two patrol reports, mine and the Batfish, one in the Atlantic and one in the Pacific. I drew the lucky straw. And so suddenly this story that I could not divulge, classified as secret, is now declassified. So that’s how I got to be here.

(Laughter).

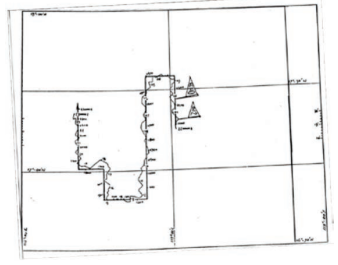

That book found its way to Russia. An admiral, retired, submarine commanding officer by the name of Alfred Berzin saw the book. He spoke no English, read no English, but there were a lot of good pictures and he flipped through the book and he saw the track chart that was in the book. It had dates on it, at that level, and he realized, oh my God, he was trailing me.

He wrote a blog describing his reaction and quoting sections of the book that he had translated into English. This blog was then translated into English and put on the net. I received in 2008 an email identifying this blog and suggesting maybe I’d like to look at it. I did, and it took me a year to finally make contact with Admiral Berzin.

That began a long period of time, up until today, where I corresponded with Admiral Berzin. We talked about all aspects of the trail. We talked about our lives, our careers, life in the United States, life in Russia, our families, our kids, all sorts of things. I found him to be a real gentleman, a professional sailor, a nice guy.

And, in fact, in 2012 my wife and I went to St. Petersburg and visited with him and had an absolutely wonderful time. He’s a spectacular guy. He had the same types of bitches about what went on in his navy that I had with my Navy.

(Laughter).

He complained about bad intelligence and poor management of the staff and all sorts of things. It seemed very similar. Our wives were very

similar. So, having made that contact, I’d like to introduce the players in this trip. Next slide.

That’s me, believe it or not, in 1972. I’ve aged. Next one. That’s

Admiral Berzin in 1972. He was only a captain, first rank, at that point.

As I said, a real gentleman. Next slide.

That’s Guardfish, another big player in this, my submarine, off Pearl Harbor. Next slide. That is an Echo II. It is not Admiral Berzin’s Echo

II. This is a generic Echo II picture.

You can see the cavities along the hull that have those launchers. There are eight launch cavities and containers. They hold a Shaddock missile, which had about a 200 mile range.

Through correspondence with Admiral Berzin, I asked a question. Did you have nuclear weapons onboard? But don’t tell me if that’s going to be a problem for you.

He came back, no problem at all. I had four nuclear weapons and four conventional weapons, and I had two nuclear torpedoes. He was well armed, as were the other submarines.

As we went south in the Sea of Japan, he popped periodically and went to periscope depth. My conclusion was that he was getting a message to give his patrol orders to him, that they had sent him out right

away and would, in fact, now update him with what he was supposed to be doing. That wasn’t the case.

He, in fact, had a missile casualty. He had a leak in one of the cable runs to his launcher number six, which had a nuclear weapon in it. That cable run could be drained into the ship, and he had surfaced when I thought he was at periscope depth, and he was trying to stop the leak, unsuccessfully.

As a result, he made a decision not to dive deeper than 85 meters, which made a big difference in the rest of the trail. At that time, our best guess is that frequently the Soviets ran at a nice round number, 100 meters, 50 meters, 150 meters.

As a result, you can take a look at the profile of our submarine and his submarine and see that there’s a space between them. If he’s at 50 meters or 100 meters, it’s good for you to be in between those so you don’t run into each other.

But there is no system, unlike in The Hunt for Red October, where they could tell exactly where that submarine was. We didn’t know what the depth of the other submarine was at all, no information for that other than the supposition of 100 meters. It turned out he and I were running at the same depth most of the time. As I pointed out to Admiral Berzin, it pays to be lucky. We never came in contact with each other.

He cleared baffles hourly for the whole trail. If he didn’t clear a regular baffle he’d change course far enough to see back into his stern area.

I’ve always described that as sort of like looking in your rear vision mirror. You’re driving along and you look in the rear vision mirror and you see what’s behind you. That’s what a submarine does routinely, and that was a major portion of his protecting himself from being trailed.

Of course, he had a terrible sonar and he couldn’t hear us. We were very quiet, and struggled to be very quiet. The whole process of baffle clearing created a certain amount of tension on board because when he turned you never knew exactly how far he was going to turn. Sometimes he would turn 180 degrees and run right back down his track.

Well, I was somewhere back on his track, and I would come to a stop. That didn’t stop the submarine, all this metal was going to coast along at pretty near the same speed. So, the two of us were approaching at each other pretty dramatically.

You wondered just how this was all going to work out. The worst possible thing is that there’d be a collision. The most likely thing is I would be detected. Neither one of those happened.

He was running too fast. He came back along his track at the speed he had been going. As a submarine increases speed its capability of detection of another ship, its sonar capability, is degraded. He didn’t slow down, so he was still blind. I concluded that actually the whole process was designed to contact another trailing submarine by use of brail. We’re going to hit them.

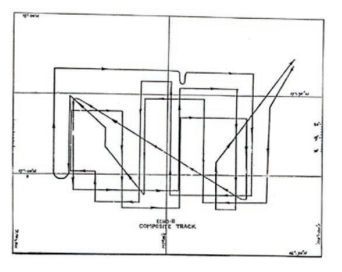

Fortunately, neither of that happened. He didn’t detect me. But we did this a lot of times. Next slide.

During the trail where we passed through between Japan and South Korea, he slowed and came to periscope depth and spent a lot of time there. I made a mistake. I stayed down below the layer.

There is generally a temperature gradient in the Western Pacific between 140 and 160 feet. If you’re above the layer and he’s below the layer, you can’t hear him, and vice versa. If you were above the layer and he’s below it, you can’t hear him.

So, he went to periscope depth and I stayed down, and waited and waited and waited. Finally, I couldn’t take it any longer and I came up through the layer, and he was gone. I was really upset because by this time I had alerted the whole Navy that I was in trail of this guy and I had detected other Soviet submarines in the group.

In fact, in my report I said I had at least three and possibly four Hen-type submarines in this group. I only knew one for sure, the one I was trailing. So suddenly I’ve lost the gas. There I am without a trail. Next slide.

This guy is the Eckland Ranger, not the Lone Ranger. Eckland

ranging is a process by which submarines determine range to another contact. To do that, one has to develop a bearing rate on the contact on one course, and then you change course and you develop a bearing rate. Through a mathematical process, using a little device on the guys cap there, you determine the range.

It’s very important. Range is the most important thing. You have a bearing on him, but you need the range. In actuality, to do that, you have to do a lot of plotting.

We took bearings on the Echo every 30 seconds for almost the whole 28 days. You’ve got to think about how intense that was. Not only that, but when he did a baffle clear, we did it every 15 seconds because we needed the information more rapidly.

We plotted a curve and determined the slope of the curve, and the slope of the curve was in fact the bearing rate. All this worked well in developing his range, and with the bearings, ultimately his course.

So, we had a pretty good handle on what he was doing when we had contact. Next slide. This is a little out of order.

When I lost contact, I was right there in the center hatch, and I realized that he had proceeded on. In some way we had missed him coming down through the layer, and I was way behind him.

So, I ran what we typically referred to as sprint and drift. You sprint after a contact, and you’re blind because you’re going too fast. You slow down, you listen, you sprint and you slow down, until you regain the contact.

I sprinted for an hour and a half. At that point, I couldn’t take it any longer. I slowed and we came down in speed, and right away we picked up a contact on our port beam, which showed by the 22 hours there, and we closed and got back into trail. I was relieved.

In The Hunt for Red October, Jonsey was the sonar man. On my submarine, a guy by the name of Harold Wilson was the sonar man. He was an expert, not the leading sonar man, but the best guy that we had aboard managing and operating the sonar system. Jonsey had picked this contact up, and I wanted some way to acknowledge his position and his feat, in some way to reward him for that.

Prior to deploying to the Western Pacific, my wife would give me a bag of smiley face pins, little smiley face pins. So, I thought I’d give this a try. I got on the 1MC and I called Willie to the control room, and on the 1MC awarded him a smiley face pin for duty above and beyond.

(Laughter).

Interestingly, I thought this might be a problem, but you have to understand, most of my crew were in the early 20s. The average age was way down there, a lot of them a lot younger than that. They took this as a great idea. They brought into it.

So, for the rest of the trail, I used that multiple times for different things that happened, including one time when I came off watch and went down by the galley. The night cook was a baker, and he had the best sticky buns I had ever had. I awarded him a pin, because dammit,

that’s what submarining is about. Next slide. (Laughter).

After this, we proceeded on down into the South China Sea. This is a depiction of one short period of time where we were in trail of the

Echo. The squiggly lines are for developing range, getting bearing rate. The straight lines were the Echo operating. Next slide.

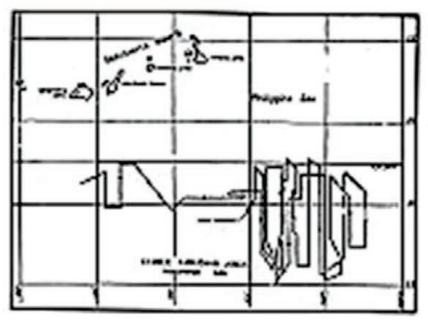

We ended up in one area pretty much in a block there, and I was able to provide that information to SUBPAC and to Washington. He was outside of his range. The Yankee station was about 700 miles away and his missile range was 200 miles.

So, he was there stationed to be available to take action if they decided that’s what they were going to do. My job was to keep track of him and make sure that if he started closing on our fleet, which was off South Vietnam our carriers in particular who were in fact pursuing a massive war and were not really geared to defend themselves against a submarine attack that was important to be able to tell the intelligence people what was happening.

At the same time, and as Dave Oliver will comment on it, we deployed every submarine we had to the South China Sea, all the attack boats, so it was like Grand Central Station down there. Submarines were all over the place. The hardest part of the problem was making sure we kept a distance from the other submarines.

Because U.S. submarines were quiet, we couldn’t hear each other very well. So, it was easier for me to find the Echo than it was for me to find another

U.S. submarine, particularly if he was running really silent, which we normally do.

So, we were in this block and we were there from May 20th to May 26th. On May 24th Nixon went to Moscow, the great summit in Moscow, with Brezhnev. That summit almost didn’t happen because of all these events because the Russians had really reacted pretty aggressively to our mining of the ports down there and denying them, the North Koreans and the Chinese, being able to bring supplies into North Vietnam.

Fortunately, everything worked out and they accepted the fact that Nixon was going to come and they wanted to go. I was told from a very good source that Kissinger met with Brezhnev in a side room during the conference and told him we know you’ve got submarines down there.

I don’t know how that ratcheted up, but ultimately, Admiral Berzin says, all the submarines were told you’re all being trailed. We knew none of the rest were being trailed, but that was okay as long as they reacted to that.

The day after that meeting in Moscow the submarine here departed leaving the area headed back for the Boschi Channel and headed north. I was elated because one, I had never run a SpecOp [Special Operation] before this.

We had been a long time at sea, and this was an intense period of time. We were tired. The submarine was tired. We had a lot of maintenance work we needed to do and we couldn’t do because of the noise it would create.

So, I thought, boy, this is going to be great. He’s going to go back to Vladivostok, I’ll ride up with him, and that will be the end of that. Well, it turned out it didn’t work out that way. One more slide.

Also, he came to periscope depth one time, a few times, when I was up. I took a photograph of him just to guarantee I really was tracking that guy. Sometimes you can make mistakes and track things that aren’t

what you thought they were. This proved it. This is clearly a Soviet submarine. Next slide.

After heading north, now he’s in the Philippine Sea. He established another area that put him in a hold there. Next slide.

At that point, I was in a position that I could not continue the trail, because I was running out of oxygen. The way submarines of the Permit class generated oxygen was with oxygen candles that burned and gave off oxygen. I only had so many candles. From the very start of the trail I knew how long the trail could possibly go, even if I used the oxygen in the emergency tanks. There was just a finite amount of time.

SUBPAC figured out that that was a problem, and so they decided to write a procedure to transfer the trail from Guardfish to another subma- rine. This procedure was a humungous procedure.

They sent it in three parts. Again, when you’re up and he’s down, you don’t know where he is. So, I was up getting the last part of this damn message. I used to stand in the radio room trying to will the machine to finish and get this thing over with.

(Laughter).

As a result of that, we were up when he came up. He spotted my periscope. We didn’t see him, I was on the way down at the same time.

After that, the whole thing went to hell in a handbasket. This alerted submarine, even with as poor a sound characteristic as the Echo II, was hard to follow and keep track of. I ended up losing him, and I was devastated.

We searched and we drilled holes through the ocean like it was go- ing out of style. In fact, Admiral Berzin said that was probably the most dangerous thing that happened during the whole time. We didn’t have good contact with him, and he didn’t have any contact with me, and we were both running around at high speed. Just terrible.

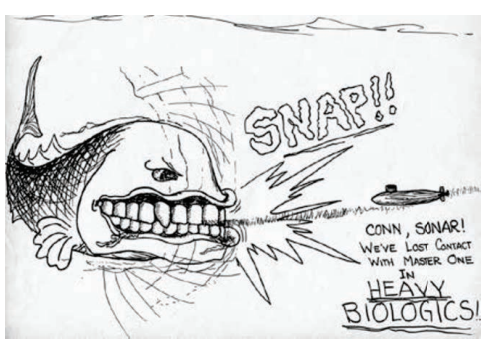

The problem with the area that we were in in the Philippine Sea was the biologics at night. Shrimp and God knows all the different types of fish that made noise, all came up at night. And there were rain squalls and all, and sonar, because of this, lost contact in heavy biologics. Next slide.

That depicts clearly how we felt. It’s just very difficult to hold contact in those conditions. That’s why I was going to periscope depth for my sched in the daytime, because I could not maintain contact and be

up in the biologic conditions we had, and stay down where I probably should have been. Hindsight is great.

So that was the end of the operation. I was told by SUBPAC I reported what had happened and SUBPAC sent me to Guam for a four letter word [I was referring to crew’s and my disappointment].

(Laughter).

In any event, Admiral Berzin, his submarine, thought I was still in trail. I have no idea what he was listening to. I had suggested some of the contacts he had were surface ships, and he got very indignant about that. He said, on my submarine we had professionals that could do this, and we can make the differentiation between a surface ship and a submarine.

You can’t argue with a guy like that, but clearly it wasn’t me. He even thought that maybe I had a secret I wasn’t telling him, that another submarine was in fact trailing him. I don’t know. I was never cleared for that. So that was the end of my trip. It was a wonderful trip. To the whole crew, it was a very uplifting accomplishment.

Everyone teamed to do this trip. I had a fantastic crew and the support of people under really tense situations. They were marvelous. I quit referring to officer and enlisted. I refer to everyone as ship- mates. We’d been shipmates on a wonderful adventure, one that very seldom does one ever get that type of opportunity.

Through the blessings of the Navy, being able to declassify this, I have a book that I’ve written with Admiral Berzin coauthoring, which tells the story of both of our lives, our careers, our families, and of the trail. I think it’s a damn good book.

(Laughter).

It will be coming out this next year, and the book’s title is From Opposite Sides of the Periscope. Thank you.

MR. ROSENBERG: I just want to point out, this isn’t the first time that this thing has really been told publicly. There are bits and pieces on the Sonalysts program, certainly in the book. When you think about this, this is something not unlike the Cuban Missile Crisis. Think about this, what was President Brezhnev or Admiral of the Fleet Sergey Gorshkov thinking? Why did they do this? What were they about?

We don’t have those larger answers. But this is one of the reasons why we have the submarine force. I also want to note one other thing, it’s in his biography.

I just want to point out Commander Minton, as captain of Guardfish for this [mission], was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. This is something that many admirals go through an entire career and never see. To give it to a commander is a truly rare occasion, and Guardfish received the Navy Unit Commendation.

(Applause).

We have the side of the story at sea, but the other side of the story most of the rest of it that we know of is going to be provided by Rear Admiral Dave Oliver, who as Lieutenant Commander Oliver witnessed a good bit of this and will also provide even more context. Sir.

RADM DAVID OLIVER: Before I do, for all of those who support David, the biologics that he was experiencing in that area are called snapping shrimp. Beds of those rise and fall between the daylight. So, all of you who really support David and support the submarine force, should eat more shrimp.

(Laughter).

They are really a pain in the butt. Let’s review it’s important to place Dave’s story in historical perspective. His patrol, which surely was a great event, took place in 1972. What was going on in 1972?

It was the 15th year of the Vietnam War. It was the 18th year of the Cold War. If you had been in high school, you hadn’t lived a year of your life in which you had not been experiencing a world at war, both a tactical and strategic war. That was your experience of the normal.

In the submarine world, 1972 was the first year in which the number of nuclear submarines became greater than the number of diesel submarines in the United States Navy, 69 to 65. Only a generation earlier, the diesel submariners had won the war in the Pacific. Those grand men with those delicate ships those brave men had won the war in the Pacific, and now there was this culture change in which they were being replaced.

And if you do not think that that culture change was emotional, then you did not go through it. And if you do not think it was a peaking at the point, that the number of nuclear SSNs became greater than the number of diesel submarines, then you were not a part of that history, because it was.

At the same time, the rest of the Navy had not yet accepted submarines truly as capital ships. Admiral Zumwalt was the CNO. Remember that the previous year, 1971, was the first year that you had an OP-02. Before that the submarine force was a part of the surface force, OP-03.

But in May of 1971 Admiral Phil Beshany had been assigned as the first head of the Submarine Directorate. That’s the first time it had been split off from the surface force, and that was not due to the fact that Admiral Zumwalt was fond of submariners because, by God, it was not his favorite force. And certainly, Admiral Rickover was not his favorite person.

(Laughter).

Fortunately, one of his favorite persons was Captain Kin McKee, who would eventually, when he was a four star, relieve Admiral Rick over. Admiral Kin McKee was not only close to Admiral Zumwalt, he was essentially Admiral Zumwalt’s right-hand, or his man Friday, and he was installed on the organizational chart as OOK and was hidden away behind a cyber lock over at Crystal City where no one could find him.

He was given whatever responsibilities Admiral Zumwalt could give to him and whatever Admiral McKee could steal.

One of the responsibilities Admiral Zumwalt gave him one morning was when the President called and said I need to drive the North Viet- namese back to the bargaining table. This was on May 7, 1972. Admiral McKee, as was his want, gave that to me because I was more foolish than anybody else he had working for him, and I had a GS-14 from the State Department working for me.

So, Admiral McKee gave that to me, also with a list of 99 things which people thought would be good ideas. One of them was the only one I can remember from the list was to drop bales of thin plastic sheets into all the harbors to go into the intakes of the engines and supposedly stop the engines. Instead, I called him at about four o’clock and I said, how about if we mine the harbors instead?

He said, that sounds good. So, I wrote it on a three-by-five card and I gave it to Admiral Zumwalt as he got in the car to go over to meet the President. He said, wait here, and so I sat on the steps outside of the Pentagon and waited.

He came back and handed the envelope back to me and said, do it. So, I went down and called 7th Fleet and said, mine Hanoi and Haiphong Harbors. And he said, as you would expect, who the hell is this?

(Laughter).

And we had a conversation about that. I then got transferred and was working for Captain Al Baciocco as an additional duty assigned in Flag Plot, when Dave made his critic report, which was the first one that ever was made, when he reports that there’s an imminent attack on the United States. As he said, he makes his report and we go through this process of passing the word to the President’s special adviser, Henry Kissinger. And Henry Kissinger is having this negotiation with the Ambassador first, and then with Brezhnev.

The key to all this, of course, from my perspective at the time, and then later on in my life, is here we have for the first time the nuclear forces the submarine nuclear forces which are essentially tied up doing the Cold War, admiring the Soviet SSBN forces, in the main. There’s some other missions. They are now involved in the tactical war, and in protecting the carriers that are down off Vietnam.

For the first time, you have a mix of the strategic and the tactical war. And it was all due to David’s initiative, because he had no orders to leave that area. In fact, those guys were turning south and there was no reason to follow them at all.

For those of us who have been there, it is a miserable, rotten area in which to try to follow a submarine, in the event that one does that sort of thing in a submarine. I am telling you, you would choose another place to do it.

It’s a miserable place to be because it’s shallow and there are all sorts of uncharted places. There are mines and reefs and currents and volcanoes and terrible things. I’m sure there are dragons.

(Laughter).

Tom saw one and reported it back once to me. And David did this by force of personality and professionalism. It was an extraordinary patrol.

(Applause).

MR. ROSENBERG: Thank you, sir. You still have to know the rest of the story, but you’ve got a good start on this.

Our next speaker is Admiral Tom Fargo. Admiral Fargo, as Com- mander Fargo, was the skipper of USS Salt Lake City, and he’s going to tell you the story of how he got tasked to host the cast of The Hunt for Red October as well as a few other people in the late 1980s. Sir.

ADM. THOMAS FARGO: Thank you, David. I was the commanding officer of Salt Lake City from 1987 to 1989. To kind of put that into con- text, this was really the end of the Cold War. The Berlin Wall, of course, fell in 1989 and the Soviet Union collapsed shortly thereafter. But my period of time, of course, was the Cold War.

As people talked about earlier, David in particular, the Soviet submarine force was a very capable adversary. But we didn’t talk about sub- marine operations. The one thing that you learned from day one when you walked onboard a submarine, and after you signed the piece of paper that said you would spend a lot of time in prison if you did talk about submarines, was you just didn’t talk about it.

Your family didn’t understand really what you were doing, other

than you were never home. You didn’t talk to your friends. You didn’t talk, as Dave said, to the rest of the Navy.

So, when The Hunt for Red October came out, the book and then the movie, it was the first real window of visibility into submarine operations, especially covert submarine operations against the Soviet Union, that the American people had ever seen. The book made an impact, but the movie really gave everybody a chance to see it up close and personal. I had a relationship with Admiral Oliver because he was my boss.

He was the Submarine Group Five Commander when I was CO of Salt Lake City. Somebody said he lived an exciting life working for Dave. I lived a tremendously exciting life.

You never knew what was up from day to day, and I can’t tell you what I was doing in the local submarine operating areas when I got a message from Admiral Oliver that said, stop whatever you’re doing, re- turn to port, and you’re going to embark the cast of The Hunt for Red October. What he didn’t mention earlier was there was an ABC camera crew headed by a guy named Fred Francis.

One would have thought that The Hunt for Red October movie was a great opportunity, one that we could never pass up, especially with Top Gun having all the success it did?

But there was some consternation about doing this movie, and there was even more consternation about taking an ABC camera crew under the water for the very first time.

We had never done that in the past. But one of the real disciples of this was Dave Oliver. I’ve got to hand it to him. We pulled out all of the stops to make sure that the movie was supported at a level that was probably never imagined before in the submarine force.

I didn’t know Alec Baldwin other than I’d watched a movie called

Beetlejuice.

(Laughter).

I didn’t know Scott Glenn other than I remembered some guy that looked like a cowboy riding a mechanical bull in Urban Cowboy. So, the first time that I met either of them was when they came to the bridge on a Sunday afternoon in San Diego. Many of you in this room will re- member what Sunday afternoons were like. The channel was just chock full of sailboats, all trying to see how close they could get to a nuclear submarine. I remember one day vividly when one of these windsurfers, which were kind of in vogue at the time, actually crossed between the turtleback of my submarine and the rudder, just to prove that he could get close.

(Laughter).

So, we came down from the bridge and as you could imagine the control room was just chock full of people. I mean, there are people all over the place. We submerged the ship, and there’s Fred Francis and the ABC camera crew and they’re working really hard to get all of the im- pressions, all of the b-roll so to speak, that they can because they knew their time was limited.

I thought Fred Francis was a pretty straight up guy, and I thought everything that he did was both honest and tried to portray the situation properly. But you had to know the angle of his story, and Admiral Oliver had shared that with me, which was that the submarine force is giving all of this away for free. I mean, the filming of the Houston, the ride on Salt Lake City, all the video from the drydock.

And you know what, he was exactly right. We’re doing that because we recognized it would hugely serve our purposes and make an impact not only externally, but also internally within the submarine force. So, while everybody was in the control room and ABC’s cameras were roll- ing, I decided it was time to get out of there and to leave that scene.

I grabbed Scott, and I said, “Scott, let’s walk around the ship and take a tour and meet the crew.” As you could imagine, the first place I took him was sonar, because it was going to play a huge part in the movie. Believe it or not, we had our own version of Jonesy.

We had Sonarman Second Class Tim Hella. Tim Hella had made the last special operation with Salt Lake City and me. He was one of these guys that you trusted emphatically. I mean, when he came to the con and said, captain this is our guy, you believed it and you took action accordingly.

Many of you here may have actually gone to sea with Tim Hella. I re- tired him about five or six years ago after he had served nearly two decades as an acoustic intelligence specialist with the Naval Intelligence Command. He was the best at that job of anybody. So frankly, we couldn’t have had a better person to pattern the film against than Tim Hella.

As we walked around, Scott met the torpedo men, the A-Gangers, the navigation team. You’d think he would ask a million questions, but he didn’t. He occasionally asked something for clarification, but he listened and he watched and picked up all of the little nuances of the relationship of the commanding officer and his crew. As you saw in the movie, he absorbed everything that he saw in those couple of days.

That afternoon we returned to port in San Diego. The deal that had been cut was ABC camera crew got the first day and then they were off the ship. I would tell you there was a tremendous sense of relief that occurred as Fred and his crew moved across the bow, and not just my crew, the actors all of a sudden started to talk more freely. You’d have thought they loved to be in front of that camera, but that wasn’t part of their job, being with ABC, and all of a sudden, the conversations got fuller and freer, and we headed back to sea.

On the way back, and I mentioned the sailboats in the harbor, Alec Baldwin came to the bridge. And, of course, by now it’s 4:30 p.m. and most of those folks skippering sailboats were pretty well oiled. Their crews were all very attractive and they started to yell to the bridge. Bald- win, of course, is an energetic, affable, engage-able person, and they yelled, “Who are you?” And he says, “I’m Tom Cruise.”

(Laughter).

So, we dove the ship and headed back down to the wardroom. I took Scott aside and I said, “We’re going to change the format here a little bit. From now on, you’re going to serve as the commanding officer of this submarine and take all reports and provide all the orders and direction to the crew.” He said, pardon me. I said, “It’s going to work out, trust me.” So, we walked into the wardroom and just to make the point, I said, “Scott, sit down here at the head of the table, the captain’s chair.” For all of you that spent time in submarines, you recognize nobody sits in the captain’s chair, not even the admiral. But I wanted him to get a feel for the responsibilities and the authority, and there was no better way to do it than to put him in the seat at that point in time.

I had a secondary objective, and that was we were about to allow Scott to give his very first order. The evening meal wrapped up and we were talking about submarines and capabilities, and every once in a while, a Hollywood story would come to the forefront. Then the phone rang at his [Scott’s] right knee. You’ve all been there; it’s a buzz that goes off and he says, “What’s that?” I said I think that’s your phone and it’s probably the officer of the deck trying to get a hold of you.

He goes, “What do I do?” I said, pick it up and maybe in your very best voice go, “Captain.”

Scott picks it up and the officer of the deck says, “Captain, we have a contact coming out of our starboard baffle area. We have not been able to classify it yet, but it’s very probably a Soviet submarine.”

(Laughter).

Scott takes the phone and puts it across his chest and says, “What do I do?” I said, “If I were you, Captain, I’d man battle stations.”

(Laughter).

“Man battle stations!” Bong, bong, bong. And, of course, we head to the control room for the typical scenario that many of us have run to train the crew on covert submarine operations. After the scenario played out and we spent a little bit of time in the control room, we headed back to the wardroom, and I would guess we talked until 1:30 a.m. in the morning.

I looked around in the wardroom, and, Scott will remember this well, there must be 26 or 27 people within earshot of the wardroom. The engineer, we let him in, but the rest of the people had their heads sticking through the little pantry hole and leaning and they’re all listening to this conversation that’s going back and forth.

The next day we went through all the evolutions that you would expect. We ran at flank speed. We maneuvered the ship, angles and dangles, and of course did an emergency blow to the surface, just to make sure that they got the feel for exactly what they were going to see, and moving all those gimbals that Mace put together to make it come out right.

The most amazing thing was that Alec, Scott and the rest of the cast internalized all this, the little things that they picked up. Many of us that were in command during that period of time had a pair of standard Navy issue — I would call them aviation frames that we wore.

Of course, we were always moving them on our head and off our head depending if we were on the periscope or the navigation stand or looking at the fire control displays. The first thing I noticed in the movie was Scott Glenn moving his glasses up and back to make sure that he was properly in character.

Tim asked me to talk just a little bit about the impact of the movie to the submarine force. I think it impacted in a lot of ways, but I sat down and had a beer before I came out here with two Pearl Harbor submariners that were junior officers during that period of time.

I said, what was the impact? What did you guys think of the movie?

The first thing that came out of their mouths was they may have used a different term — but they said it wasn’t hokey. It was a pretty fair rendition of what we do day-in and dayout. They said maybe that trip through the sea canyon at flank speed may have been a little bit on the edges, but that’s what we do.

The second thing was it did have an impact on morale, on the ship. As I said, we weren’t able to talk about this and nobody really knew what we do. It provided those junior officers — they had a sense of purpose, but a sense of pride that other folks, their families and the average American, understood what they were doing.

The third point they made was that it really did capture the relationships. Submarines are different, as we know, the dependencies of every- body on each other, the relationship of the captain and the crew, and the relationship of each crew member to each other. They felt that was an especially important point of the movie.

The last thing they said was that the last thing that I would point out is that the timing was really good. As I mentioned earlier, the Berlin Wall had fallen and the Soviet Union was going away, and this was a point in time where people were starting to write the history of the Cold War. It was important for them to understand what a key element of our success really was.

So, let me thank you all. I want to thank Mace for being here. I’m sorry Scott couldn’t be here. We stayed in touch over the years and I know this has been very important to him. Mace and Scott and Alec did a fabulous job after the movie and even to this day, of talking to the attributes of the submarine force, our sailors and really our Navy, and its importance to our nation. So, thank you very much.

(Applause).

MR. ROSENBERG: Thank you, sir. Our last speaker is Mace Neufeld, who was the producer of The Hunt for Red October. We are very privileged to have him, for a number of reasons, not the least of which is this all came about very, very suddenly within the last two weeks, and we are delighted that you were able to make it here, because this is true of the rest of the story.

MR. MACE NEUFELD: The Hunt for Red October was not an easy film to make. At the end of 1984 I sent one of the young men who was working for me and my production company down to the Dallas book fair, and he came back with a book which he picked up at a small booth where the Naval Institute Press was selling their books about knot tying and engine maintenance, and this happened to be the first work of fiction that the Naval Institute Press had ever published. He said, this could make a movie.

So, I took it on and I put it on my night table, where it stayed for three weeks. I tried to pick it up once or twice, but I put it down and didn’t pay much attention to it, until one day, Time magazine mentioned that President Reagan had a favorite book, which was causing a lot of excitement in Washington, D.C., and it was called The Hunt for Red October.

I said, I’d better read this book. So, I read the book very quickly. It’s not easy to read that book quickly because Clancy has a lot of technical talk in the book. Actually, the way Tom wrote was he could take an entire chapter to explain how Jack Ryan could hit a golf ball.

(Laughter).

Everything was technical. But at any rate, I got ahold of the people who represented the Naval Institute Press and I offered them some money to option the book. I said, you’ve got to make the deal quickly. I don’t think the agent actually had ever read Time magazine and knew that this was Reagan’s favorite book, so I insisted that he close the deal as quickly as possible, and we closed the deal at the end of that week and now I had an option on the book.

At that time, I had what they call a first look deal at MGM, which meant that any material I developed I had to show them first. If they turned it down I could go elsewhere. So, I showed them the book and

they did what most studios do, they sent it to the story department be- cause executives don’t read book, they read synopsis.

The Hunt for Red October was a difficult book to synopsize and MGM turned it down. I had an 18-month option on this, this was early 1985, so I went to each studio and each studio did the same thing. They turned it down. I had gone around to all the studios and I had an option on this book which nobody wanted to do.

However, I had a friend by the name of Ned Tanen, who was then the head of Paramount Pictures. I found out that Ned was flying to London the following day and I talked to him on the phone. I said, do you have any scripts or books to read on the plane? He said, no, I was planning on sleeping.

I said, I have this great book The Hunt for Red October. He said, I think I saw some coverage on that. We turned it down, didn’t we?

I said, you did, but you didn’t read the book. If you read the book and you land in London and you don’t think this can make a great movie, you’ll never have to return another call of mine. That was great incentive for him.

(Laughter).

So, he landed at Heathrow and he called me from Heathrow and he said, you’re right. This could make a great movie, but it’s going to be very expensive. I said, no Ned, it’s not going to be.

He said, what do you think it will cost? I said, $16 million. I just plucked that out of the air.

He said, you can’t do that without the Navy’s cooperation. I said, I’ll get naval cooperation. He said, I’ll put it in the contract, if you don’t get it we won’t make the move. I said, fine.

At the time I was shooting a film called No Way Out, with Kevin Costner, and we were shooting in Georgetown and in the basement of the Pentagon, the commercial area. No Way Out was about a naval officer who turned out to be a Russian spy. About that same time, I got a call from Washington that said the Secretary of the Navy would like to meet with you to discuss The Hunt for Red October.

So, I went up to meet with the Secretary of the Navy. We sat around a big table and on my right, was the head of the submarine force, I don’t remember his name, and the Secretary of the Navy was very enthusiastic. He said, we’d love to make this movie, what do you think, sir?

He [head of the submarine force] said, well, I don’t think so. We’re the silent service. I don’t want to talk about this very much. My stomach dropped to my feet because I knew I had a contract that said we had to get naval cooperation. And I didn’t want them to know that we were shooting a movie about a Navy officer who turned out to be a Russian spy.

(Laughter).

Anyway, I went back to California and about four weeks later the phone rang and they said, it’s the Secretary of the Navy calling, he’d like to invite you and your screenwriter for a ride on a sub. So, we flew down to Norfolk and we boarded the Rickover, which the captain at that time was Jay Cohen, along with the Navy chaplain, who had just finished Rickover’s funeral service, and we went on a four-day cruise in the North Atlantic. I thought to myself, if I never get this movie made, it was worth optioning the book because I got this ride on this submarine.

(Laughter).

Anyway, if you’ll bear with me I’d like to read you a letter that I got right after I optioned the book. The heading is the O.F. Bowen Insurance Agency. It says, “Dear Sir, back in September of 1983 I had lunch with Captain Edward Beach, U.S. Navy Retired. He was the first man to tell me that The Hunt for Red October would make, quote, ‘one hell of a movie.’ I took this seriously, since Run Silent, Run Deep enjoyed the same good fortune. You, however, are the professional who put money on the table and I must first of all express my deepest appreciation for your faith in my book’s dramatic potential.

As you doubtless know, I am a rank amateur in nearly everything except insurance. The Hunt for Red October is my first novel and I still don’t know a whole lot about the publishing business. My knowledge of the movie industry is limited to my experience sitting in theaters.” That changed a lot later.

“Nevertheless, I hope you will give some brief consideration to including me in your team, if for no other reason I have acquired a good deal of knowledge about how the American and Soviet navies work. I’ve gradually accumulated a number of contacts within the naval com- munity that might be of use to you. And I feel that my status as a civilian would be beneficial here, since explaining all the jargon and technology

to civilians is fast becoming my specialty.

One thing that might be of particular interest to you is the fact that the average crewman’s age on American and Soviet submarines is under 23. The boats, parenthesis — submarines are called boats, not ships — close parenthesis, are driven by children. Like pilots and astronauts, they speak a special language for which there is a special manual which I have. As with NASA, their special language is actually rather dramatic sounding.

Whether or not my services would really be useful to your company is a business decision you must make for yourself. I could have no complaint if you make a successful production without me, but I learn fast and I’m a team player. I think I would be an asset to your company. In any case, I look forward to meeting you in the near future to express in person my gratitude for your decision to make my book a dramatic reality. Yours very truly, Thomas L Clancy Jr.”

This was dated May 1985. I push forward to September of 1988. I still hadn’t made this movie.

“Dear Mace, I was delighted to hear today that John McTiernan has been chosen as our director for Red October. I heard a few weeks ago he was interested in the project, and calling him learned he’s the guy who directed Predator, which I thought was a damn fine bit of science fiction adventure. Soon after, I went to see Diehard and right after coming home I called him to say I wanted him to be my director.

In addition to his obvious technical talents, his work evidences a remarkable aware- ness for the reasons why people do things, which is to say that his views largely coincide with mine, and are therefore brilliantly accurate.”

(Laughter).

“Speaking with him only makes things look better. He makes my kind of movie because he’s my kind of guy. Obviously, the current squabble with Paramount limits my ability to cooperate with your pro- duction.” At the time, Paramount was trying to work out a deal to do his next book, which was Red Storm Rising, which they never did do.

“I want to cooperate and having McTiernan on the project increases my desire to do so. I hope we can get this little problem settled and maybe I can help you deliver this movie. I’d like to see how you do your job and I’d like to think that I might make a useful guy to have around.”

Things changed over the years. We finally made the movie in 1989. It came out in 1990, and it changed both of our careers. It was the first of six Jack Ryan movies that I made, and it was the first of the books that made Tom Clancy the best-selling author in the world at that point.

I was fortunate to meet Dave Oliver, who was in San Diego at the time. I went down to have dinner with he and his wife Linda, and with John McTiernan, my director. After dinner Dave said, come on, I’ve got a little surprise for you.

We went outside and we took a little walk, and he gave us construc- tion helmets. We walked into a graving dock and there was a nuclear submarine. John McTiernan said, isn’t that fantastic, can we shoot that? Dave said, well what do you think, I brought it in for painting, wink, wink?

(Laughter).

Sure, you can shoot it, but you can’t shoot this part of it. So, if you see the movie, that’s actually a nuclear submarine and we shot the screen in the graving dock courtesy of Dave Oliver.

The script was written by Larry Ferguson and Donald Stewart.

I didn’t realize at the time we were making it that it would be the be- ginning of a franchise, and after that we made five Jack Ryan movies with four different actors: Alec Baldwin, Harrison Ford, Ben Affleck and Chris Pine. Currently we’ve just finished an eight-hour mini-series for Amazon which will be streaming next June or July with John Krasinski playing Jack Ryan. That will be our fifth Jack Ryan, but it doesn’t seem to matter.

Anyway, we had a wonderful time making this film. One major problem which I’ll tell you now is that we had originally cast Klaus Ma- ria Brandauer to play Captain Ramius. We started shooting the film and Brandauer was supposed to show up in the third week.

I had him on the phone and I said, Klaus you haven’t sent your con- tract in. He said, well, I need 10 days off. I said, what do you mean you need 10 days off, you’re supposed to be here in three weeks?

He said, I shot a movie for a friend and I am editing it and it has to be ready for the Cannes Film Festival and I’ve got to deliver it to him. I said, Klaus, I can’t shoot the movie without your signing the contract. He said, well, I’m terribly sorry.

Here we were shooting this film, we were in the second week, and I have no Captain Ramius. I got a call from an agent by the name of Mar- ty Baum who worked for Creative Artists Agency, and he said, I heard about a book you have and my client, Sean Connery, might be interested in it. Why don’t you send it to him?

So, I said, okay, where do I sent it? He said, he has a house in Major- ca, send him the script. So, I faxed it. There was no email at the time, so I faxed the script over and waited anxiously, because we were shooting this film with no captain. Two days later the phone rang and it was Sean Connery.

He said, Mr. Neufeld, this is Sean. I said, yes, Sean. He said, I read your script but I don’t think I can do it. I said, why not? He said, it’s not politically correct. We have Perestroika now, there’s no Cold War.

I said, well, the movie starts by saying before the end of the Cold War these events happened and been denied by the Soviet and the Amer- ican navies. He said, I didn’t see that. I said, I’ll fax it over to you.

So, I faxed it over to him. He called me back the next day and said, okay, it makes sense now. But I need some big speeches for myself. There are no big speeches in this script.

I said, we’ll get a writer to work right away. He said, who can you get? At that point — believe me, it was just fate — John Milius was pass- ing my office door. I knew that John had directed Sean in The Wind and the Lion.

So, I said, John, come here. He said, what? I said, Sean Connery is on the phone. He wants some work done on the script. Here, talk to him.

So, he goes, yes, yes, yes, yes sir, yes sir. He said, he’ll do it. I’ve got to write some lines for him.

So, we revised the script and I thought I was home free. Now we had Sean Connery, a great movie star, to play Marko Ramius. I left my office and I stopped in front of the commissary and there was one of the co-heads of production of Paramount.

I was all excited. I said, we’ve got Sean Connery to play Marko Ramius. He said, Sean Connery can’t do a Russian accent. I said, he doesn’t have to.

He said, well, he’s got a Scottish brogue. I said, I know. He said,

well, how will people know he’s a Russian officer? I said, we’ll put him

in a Russian uniform with a Russian hat. (Laughter).

He said, I’ll have to think about that overnight. I went back to my office and said, what’s going on? We’re shooting on stage seven and I don’t have a Marko Ramius.

The next day the phone rang, I was in my office, I was not on the set, and Frank Mancuso, who was the chairman of Paramount, asked me to come over to the set. He had a set of papers in his hand. He said, look at these reports. These were screening reports for Indiana Jones, which had Harrison Ford and Sean Connery, and they were ecstatic.

He said, can you get Sean? I said, we can get him. I said, there’s a problem. He said, what’s the problem?

I said, he can’t come next week because he’s got a golf tournament in Scotland. He said, well, can we accommodate him? I said, give me half an hour.

I went back to the production office and we rearranged the shooting

board. I came back, and he said, what will it cost? I said, it will cost over

$600,000. He said, do it, and buy him a set of golf clubs and send them to him with my complements.

So, we sent the golf clubs to Sean Connery. He showed up on the set. And we shot The Hunt for Red October, which almost didn’t get made.

(Laughter/Applause).

MR. ROSENBERG: We’re going to open the floor for some questions.

Does anybody have any thoughts?