The implosion of the Soviet Union marked the disappearance not only of a threat but also of the political entity to be deterred. Strategic nuclear deterrent policy was left without legs and so has been dormant for twenty years. The rise of Vladimir Putin and his open rearmament programs in Russia and the entry of a nuclear armed and aggressive China into the great power arena come at the same time as the end of life of America’s existing strategic weapons systems.

Proliferation of nuclear weapons by non friendly states adds new dimensions but does not change the basic dynamics of deterrence that demand viable and powerful strategic weapons and their delivery systems. Finally, the large costs of modernization of the nation’s strategic nuclear forces demand attention from legislators, defense executives and military leaders.

These factors force the return of debate on the nature and composition of American strategic deterrent forces. In the theoretical discussions around these issues, propelled by the end oflife of present systems, knowledgeable voices, careful reasoning and measured opinions are im portant too important to be left to the academic and the inexperienced. For those naval officers who concern themselves with strategic deterrence and nuclear weapons, the need for forces other than those em barked in US submarines seems counterintuitive.

The utility of weapons beyond those deployed in a secure, safe and flexible structure that possesses all the attributes for strategic deterrence is not easy to understand. Naval officers are not alone with this question. The utility of land-based forces has been questioned as far back as 1961 when the conclusions of the Strategic Air Command War Game that year recommended eliminating ICBMs .i However, other actors in these discussions remain convinced of their utility.

Today the technologies required for each of the TRlAD’s delivery systems are well developed. The weapons themselves are fruits of eighty years of development and no longer need great invention. Alternatives to their current deployment and basing have been thoroughly examined and rejected. Really old practitioners continue to ask questions, e.g.”… are you considering concealing the ICBM’s?’ii to which the answers are “No”.

The result of this thorough examination and expertise on one hand and the end of life of the present systems on the other is an opportunity to remake the US strategic arsenal on a “Clean Sheet”. If no systems existed, what would be the most logical and most effective new one(s)? Participation in this discussion by persons knowledgeable about the various theories and facts is important particularly in areas where many of the participants have little knowledge and no experience in pertinent issues, like the sea.

As with any issue reopened after being long dormant, those newly engaged need to ask, “How did we get here”? Theories about nuclear deterrence began to be formed in the late 1940’s when it became clear that the United States would not long be the sole possessor of nuclear weapons. American military strategy at the time was dominated by officers of the Air Force who grew up in the advocacy of “strategic bombing”. Airplanes appealed to the political leadership as a strategy that reduced the need for building a navy and having to maintain a large army.

Heirs to the technical research establishments built up during World War II were first to consider the situation in which the Soviet Union would also possess atomic weapons and delivery systems that eventually would threaten the United States. The RAND Corporation, a Federally Funded Research Center established during the war by the Air Force, housed the initial research on how to conduct a war in which nuclear weapons might be used. While RAND was the center point on theories, other institutions and academic enterprises joined as the “balance ofter ror” was explored and debated. iii

Well before nuclear deterrence began to be explored, the victors at the end of World War II seized the German ideas, equipment and personnel that had produced the V-1 cruise missiles and V-2 rockets used to bombard Britain. The services were slow to develop these systems because the nuclear warheads themselves were very large airplanes were the sole delivery system.

The Air Force began exploiting the V-2 but development was not encouraged by that service’s leadership’s attention to bombers. The land launched missile languished until 1957 when the Soviet launch of Sputnik added national impetus. The Navy created a carrier based large bomber to participate in the strategic nuclear weapons missions.iv Rockets, then liquid fueled, were considered too hazardous for shipboard and so attention turned to cruise missiles.

Nuclear armed REGULUS cruise missiles went on patrol in submarines in 1955; deployments that lasted until 1964. With dramatic reduction in the war heads’ size and weight, missile development accelerated in the Air Force and the Navy. The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Arleigh Burke, established the POLARIS program aimed at putting solid fueled ballistic missiles on submarines. By the late nineteen fifties the elements of the TRIAD were borne.

As the technologies grew, ideas about what an exchange of weapons would mean absorbed the interests of political scientists and related scholars across the country. Concerns of the uniformed military focused not so much on use or utility of the weapons as on force structure and technical improvements.

The vulnerability of land based strategic forces became apparent in these studies leading to hardening the land based missile launchers, relocating the bomber bases to southern states and constructing a series of warning systems. At the same time, the POLAR IS Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM) became the number one priority program in the Navy. By the beginning of the Reagan ad ministration, the TRIAD, a “bastard child of inter service rivalries” ac cording to Frank Miller, was in place.

But the vulnerability of basing anchored ashore was never solved; the many attempts to design such a basing mode all foundered on the physical realities that it could not move or if it could (train mobile), the required footprint was too large to be realistic. Unless the land based forces were used to preempt (first strike) an option that seems never to have been considered after General Thom as S. Powers retired from command of the Strategic Air Command in the early sixtiesv every land-based force had to rely on a warning system and short fused command and control arrangements in order to “Launch Under Attack” (LUA).

Development of the ICBM and SLBM missile systems were not enthusiastically endorsed within their individual services. The Navy’s aviation community violently objected when funds for a carrier were shifted to the POLARIS building program. The bomber wing of the Air Force was indignant at the diversion of monies from bombers to missile development.

Studies of the various basing alternatives through the sixties and seventies all demonstrated the survivability of the sea based system. The Office of the Secretary of Defense, not knowledgeable in maritime matters, suspicious of the Navy’s motives, and anxious to avoid the cost associated with the sea based leg was not receptive to these conclusions.

Repeated attempts to find a base for the land-based missiles that bolstered the economic arguments all lost in face of the utility (dependent on LUA) and survivability (none). When TRIDENT D5 SLBM was fielded with an accuracy equal to the land-based missiles, the final argument boasting that only ICBM’s possessed “hard target” counterforce (able to destroy Soviet ICBM sites) lost purpose. vi However even after the D5 addressed the last advantage of the ICBM to achieve the purposes of deterrence, the three different delivery systems and basing modes each with its own advocates, vested interests, and performance criteria continued.

As the Soviet Union imploded and disappeared the value of strategic nuclear weapons decreased and senior leadership and attention in both civilian and military circles drifted away from nuclear weapons matters. What little public discussion of the nuclear strategic weapons that did exist focused on reduction of numbers of nuclear warheads.

Evaluation and analysis of strategic weapons were reduced to a Congressionally mandated Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), ordered to be coincident with the quadrennial defense review. The NPR’s aim was to be a “basis for establishing United States arms control objectives and negotiating positions.” vii Regarding the TRIAD, the results of these reviews can be summarized as “Steaming as before”.

This shift of attention reverberated through the Defense Department with unwanted results _viii Problems in the Air Force in inventory and deployment led to questions about how the Navy escaped these same problems. Personal attention at the operating level, knowledge of technical details a heritage of pre World War II submarines reinforced by Admiral Rickover’s strict regimen, direct and immediate involvement of commanders at the basic organization levels and intrusive and demanding oversight by their superiors mark the Navy’s custody of nuclear weapons.

Direct and personal experience in the operation and maintenance of nuclear reactors and in the custody and handling of nuclear weapons exists at every level of command. This personal involvement, while often a matter of jest by fellow officers outside this community who comment that, “The Navy’s nuclear weapons are managed by the most obsessive compulsive organization in the world”, is nevertheless widely known and respected both in the Navy and by civilian scientists and political leaders.

Maintaining this reputation is critically important. The trust engendered in and by each person involved with development, maintenance and deployment of these weapons relies on continuing high standards of care for these world ending devices. In coming years, the issue of the composition of the nuclear weapons related systems may become subject of serious debate.

In those debates casual accusations of inadequacy and inferiority of the submarine based nuclear forces capability need to be answered whenever the subject arises. While less than 5% of the Navy’s personnel are engaged in the Strategic Deterrence Enterprise, this is the Navy’ s primary mission requiring attention if not dedication from “all hands”.

Every officer who has served at sea knows how hard it is finding and attacking submarines. This practical expertise is important in informing decision makers of the utility of the submarine based component of the TRIAD and preventing perversion by weak or specious arguments.

Such representation is important because currently attention on this aspect of our national defense centers only on their cost. This emphasis on the budget and national debt create the hazard of turning strategic nuclear weapons into an affair of accountants rather than of political leaders, strategic thinkers, social scientists and military officers. Part of the campaign of advocates of land-based systems is infer ring the missiles based at sea are in some ways inferior to those based ashore.

A recent tract by Major General Roger W Burg USAF (Retired) published by the Air Force Association advertises the utility of strategic deterrent forces based ashore. ix None of his arguments are new. Sever al errors and questionable assertions demonstrate an ignorance of the sea based environment or technologies. Promoting the Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) and long-range bombers in his analysis, General Burg provides a list of attributes that can be helpful in identifying the aspects that emphasize the advantages of submarine based strategic weapons.

“The ICBM’s represent an unambiguous target. An enemy must at tack these to try to limit damage to his own country. Such an attack would be apparent and the source identifiable as opposed to incremental reductions of submarines or bombers by secret or sneak attacks.” (There exists no plausible threat to submarines underway at sea.)

“ICBM fields are a weapons sink. An attack on these heavily fortified silos would largely deplete an enemy weapons’ inventory.” (Missiles based in submarines provide no aim points.)

“ICBMs high alert rates make them more responsive than bombers and submarines missiles.” (Time on target is the operative metric. Be cause submarines can maneuver to shorten the time of flight SLBM · time on target is substantially less than that of land-based systems.)

“Land-based communications’ links provide faster response to orders than those to submarines.” (Speed of response not a factor in deterrence; communications to submarines on alert are as fast or faster than to land-based sites).

“The 400 ICBMs are an offensive threat that can overwhelm any defense.” (70% of US strategic warheads are based on submarines.)

“ICBMs have a long history of reliability which will hedge against any disruption of one of the Triad’s other legs.” (Only SLBM’s conduct end to end firing missions from operating launch platforms to target).

“ICBMs have the lowest operating costs and lowest recapitalization cost.” (True.)

“Because of their long slow flight times of bombers, weapons deployed in them are less threatening; thereby improving strategic stability.” (Invulnerable, able to restrain action without losing ability to strike, SLBMs contribute the most to stability in confrontational situations).

“The visibility of bombers permits their use as a signal in confrontational situations.” (Not a unique property of bombers; many other forms of signaling exist.)

Understanding that General Burg’s motive is to define the utility of the land-based systems vis-a-vis other systems, i.e., ones based at sea, his lack of comprehension of the sea, appreciating the complications of anti-submarine operations and understanding of long haul crisis communications are evident in what he sees as weaknesses of the sea-based system. His analysis of the merits of these forces does not contain any argument not aired in the 1980’s during the debates around MX Basing vis-a-vis the Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM).x

One particularly fallacious aspect of these propositions is the assumption that speed is required to make deterrence work. This is a residue of the Launch Under Attack requirement in which the ICBM is grounded. Strategic nuclear deterrence does not rely on speed of response but on surety of weapons and will. xi

Long distance communications, the life blood of maritime operations at sea, are not well understood in the other services or the public in general. Unlike assertions regularly echoed by persons who are ignorant of the actual facts, independent studies since 1987 have determined that communications to submarines are as reliable and efficient as those to ground based forces. xii

That ICBM’s are needed as a hedge against failure of other legs of the TRIAD is based on the proposition that maybe someday anti-submarine measures will threaten the continued survivability of submarines. The wish that space based technology would make the oceans transparent, a common hope hyped in the 1980’s, seems to have died, sunk by geography and physics.

A new proposition that giant data bases might someday allow analytical determination of the submarine positions ignores the need for search vehicles to provide inputs on a real time basis. Operations analyses like this can and do work in relatively small areas with multiple sensors over short periods. Persons understanding sensor limitations and the probability of detection in large ocean areas realize that such measures are futile regardless of the size of the computer or its data capacity. There exists not even a vision of a mechanism that threatens the survivability of the submarines which operate avoiding detection as a priority.

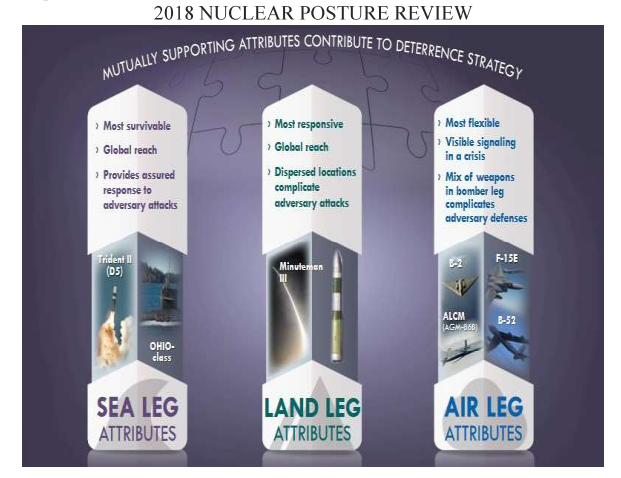

The Nuclear Posture Review published this March offered an opportunity to evaluate how these various basing methods perform, how they compare in effectiveness and cost, and what future needs should be considered in their continuance and/or modernization. However, no alternatives to the current TRIAD were part of this policy review. The at tributes of each of the three systems were restatements of those repeated in previous summaries. xiii

These sorts of studies require the attention of persons who know and understand the sea, its vastness, cloak of invisibility and freedom for maneuver. Articulating these characteristics is not an easy task nor one performed well by persons who lack an experiential understanding, as General Burg demonstrates.

Regardless of technical propositions, the future of American strategic nuclear arms is in the hands of political leaders. For a myriad of reasons, the active duty components of the services will not willingly enter a public debate on the utility of arms of another service.

The mantle of “Jointness” suggests that flag officers in joint billets in particular, e.g., COMSTRATCOM, but active duty officers in general, not comment on issues other than to “promote the Administration’s agenda” which currently appears to be modernizing all three legs. However, this “gentleman’s agreement”, should not inhibit those knowledgeable from avoiding explanations of the advantages of the sea based leg.

On the contrary, those singular facets of the sea-based systems that are unique to its utility need to be explained and promoted. Policy makers, most of whose experience with the sea involves flying over it, should not be left adrift without the experiential knowledge that comes from those whose Iife has been spent on, over and under the sea. xiv

When he promoted development of a strategic weapons system based in submarines, Admiral Arleigh Burke was accused of trespassing on missions assigned to the Air Force. The most authoritative military voices in the debate over MX Basing were Admirals Hayward and Watkins, Chiefs of Naval Operations, who questioned the theory behind the proposed basing schemes and the devotion of so much of the Defense Department’s resources to them.xv Their substantial grasp of the fundamentals of deterrence and alternative weapons systems shifted the country’s strategic focus from land to sea. As in times past, measured arguments and strong and experienced voices are needed to influence the next generation of these weapons’ systems.

The compromises that resulted in the TRIAD continue and probably will pass into the future because change requires more political energy and analysis than exists, at least at present. The Nuclear Posture Review summarizes the arguments for the TRIAD,

“The increasing need for this diversity and flexibility, in turn, is one of the primary reasons why sustaining and replacing the nuclear triad and non strategic nuclear capabilities, and modernizing NC3, is necessary now. The TRIAD’s synergy and overlapping attributes help ensure the enduring survivability of our deterrence capabilities against attack and our capacity to hold at risk a range of adversary targets throughout a crisis or conflict. Eliminating any leg of the TRIAD would greatly ease adversary attack planning and allow an adversary to concentrate resources and attention on defeating the remaining two legs. Therefore, we will sustain our legacy triad systems until the planned replacement programs are deployed.”

However, as costs mount, the modernization programs will come under greater scrutiny. The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review will not be the last. While the Air Force leadership might favor funding the new bomber at the expense of the ICBM, internal interests will continue to promote the ICBM leg and elected officials in the affected manufacturing and basing states will lobby hard for that missile system. Navy spokesmen cannot ignore these discussions or allow American political or economic concerns to work unchallenged to the detriment of maintaining the sea based leg.