ACTING DIRECTOR, UNDERSEA WARFARE DIVISION OPNAV N97

Thank you, Admiral, for the kind introduction. It’s great to have an opportunity to speak here today at our annual gathering of the Dolphins. My intent this morning is to review and explain how we in the Undersea Warfare Division execute the collective vision that you’ve heard today, and distill it into our priorities consistent with the direction of our Secretary of Defense, Secretary of the Navy, the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Tofalo, Admiral Caldwell and the other leaders here today.

You’ve heard over these two days a consistent message of concern surrounding our fiscal environment. As a result of this continuing budget uncertainty and the suppressed resourcing levels in the Budget Control Act, it is very difficult for me to stand before you today as the Undersea Warfare Resource Sponsor and give you an update on a budget that I don’t have, or a fiscal outlook that I cannot predict. I can tell you with certainty that the last eight years of continuing resolutions (CRs) and the Budget Control Act (BCA) have impacted our Navy in terms of training, ship maintenance, and modernization.

Admiral Tofalo already quoted our Secretary of Defense who says it much better. “No enemy has done more harm to the warfighting readiness of our military than sequestration.” So given the uncertainty of our budget today, instead I will focus on our priorities and our warfighting requirements.

Before we start any discussion of priorities I’d like to ensure we’re all on the same page in terms of guidance and direction. As you know, in the last year we’ve had a change of Administration and a resulting new Secretary of Defense and Secretary of the Navy. I would summarize the collective direction, including that from our CNO, to ensure today’s force is ready and lethal; then focus any additional resources we have on growing “quantity and quality” for “capability and capacity” of those “ready and lethal” forces. Of our forces, we prioritize a safe and secure nuclear deterrent and fielding a decisive conventional force.

Finally, we must look for additional resources for growing our force first from with in, through reform and better processes, before we ask for additional resources from Congress. So given that overarching guidance and in accordance with Admiral Tofalo’s commander’s intent, we “bin” this direction into two primary undersea warfare domains.

The first is Strategic deterrence; we’ve talked about it a lot. We’ve talked a lot about it for a reason. It is our number one priority. It is non negotiable. It is fully funded, fully resourced and fully supported, for both today and tomorrow.

The next bin is what we call theater undersea warfare said another way to deliver effects within or from the undersea. As you know, this warfare area is not solely the domain of N97, however on the Navy Staff we are the advocate for Undersea Warfare requirements to make sure they are known and resourced appropriately to maximize our effects in both peace and war. We then translate these domain focus areas into discrete priorities.

Again, these should not be new to you, but we’ll review those just so that we’re all on the same page. We document these priorities in our “Integrated Undersea Future Investment Strategy” (IUFIS) which was started by Admiral Connor in 2011, and we refresh it and up- date it periodically. The strategy is our guide to meet our leaders’ intent for both Strategic Deterrence and Theater Undersea Warfare.

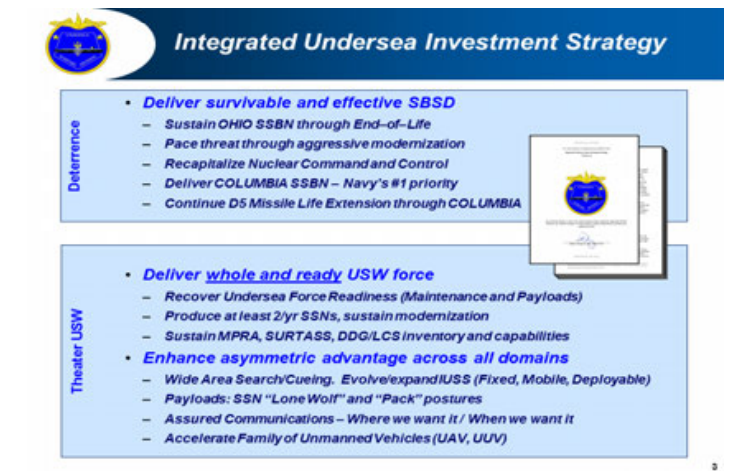

For Strategic Deterrence, as discussed, this is our Nation’s Number One Priority; we must sustain the most survivable leg of our nuclear triad and ensure it remains credible and capable. Our priorities for Strategic Deterrence are simple. In order to be effective we must have reliable and capable ballistic missile submarines now and in the future, from OHIO through COLUMBIA. This submarine must be able to host and launch a reliable and effective ballistic missile at ranges sufficient to ensure we meet Presidential intent, while also ensuring our submarines can evade detection and execute their mission in their launch areas.

Finally in order to be credible and capable, our submarines must be able to receive direction from our Commander in Chief with 100% reliability. This requires a redundant, resilient, and reliable command and control system.

For Theater Undersea Warfare, this is our ability to deliver effects within and from the undersea. Again, we have simple priorities. We must ensure the forces we have are ready and lethal. First, we ensure our Submarine Force has sufficient force structure to deter, or if necessary, defeat the enemy from the undersea.

Next, we must ensure our Anti Submarine Warfare Forces are capable of denying our enemies’ submarines the same undersea advantage we currently enjoy and exploit. We will continue to exploit our undersea advantages to deliver payloads designed for use by our submarine skippers and by the operational commanders, what we call “lone wolf” and “pack” weapons. We have embraced unmanned systems as an undersea force multiplier, and we intend to accelerate their introduction into the fleet.

So given this view of our high-level priorities, I want to dive into a few more details on a number of them. The first is a review or a primer on our approach to Readiness. Readiness is obviously fundamental to both Strategic Deterrence and Theater Undersea Warfare.

Clearly the topic of Navy readiness has been in the news with the tragic events in the Western Pacific. As a member of the Navy Staff’s Warfare Requirements Division under Admiral Merz, I can assure you our readiness challenges are front and center on his mind, as well as all of our Division Directors. We take seriously our responsibility to support the Fleet through proper resourcing to ensure our ships, submarines, and aircraft and their Sailors and Marines are ready for both their peacetime and wartime missions year round.

As a result, I want to review with you how we are working to address our Readiness challenges through the lens of the Submarine Force. I’m sure if I polled the people in this room as to what “Readiness” means, I would get many different answers. So, here is how we look at readiness from the OPNAV perspective and how we resource that Readiness.

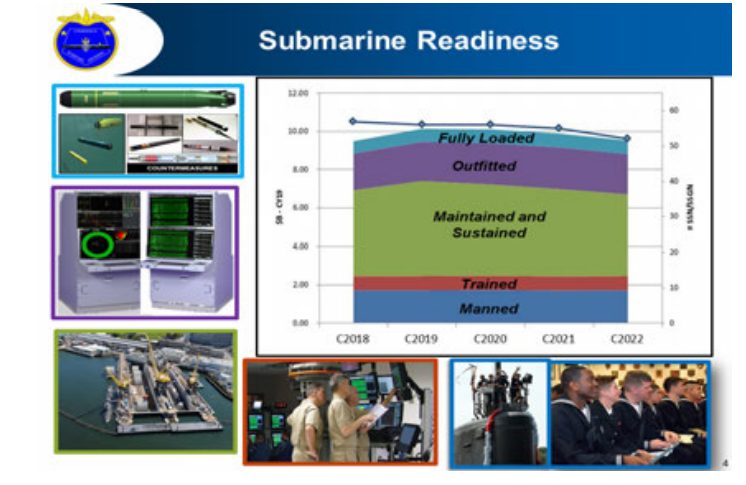

What you see here is a basic graph showing our total number of attack and guided missile submarines over the next five years. Overlaid on this graph you will see the resources we have budgeted in order for Admiral Tofalo and Admiral Caudle to keep their ships ready.

To be ready our submarines must first of all be “Manned.” For man power folks that means we must have a “body” for every “billet” and every one of these bodies must be appropriately trained and have the required skills.

Next, these crews must be “Trained” through an effective training pipeline with modern training systems to provide initial skills and team training for our new Sailors. We must also have effective training systems to ensure our submarine crews sustain and improve their combat expertise as both teams and in individual skill areas.

Then, our submarines must be “Maintained and Sustained.” Admiral Tofalo has already discussed this. This is what we call our intermediate and our depot level maintenance, our maintenance when our ships are in homeport and the maintenance conducted in our public shipyards. As we discussed, over the last five years or more, we have suffered from a mismatch between the work we need to do and the work we funded, what we call the workforce mismatch. This mismatch was the result of a number of factors, pressures to absorb the budget cuts inflicted by the Budget Control Act being the primary driver.

Recognizing this mismatch, we are committed to fixing both sides of the equation. The Fleet and NAVSEA are improving their scheduling and their maintenance planning process to ensure we fully capture the workload. On the workforce side of the equation, the Navy increased our investments in Readiness in the Fiscal Year 2017 base budget and supplemental, and requested $3.4 billion more in Fiscal Year 2018.

For our carriers and submarines, that investment is going to increase our civilian workforce at our four public shipyards. We’ve also used temporary measures to rebalance our workload by contracting with our two private nuclear shipyards to conduct four submarine overhauls, most recently USS Boise. These efforts will take time to fully take effect, however the benefit will come from increased operational availability for our attack submarines.

As you know, we prioritize our ballistic missile submarine and our carrier maintenance in our shipyards so our attack submarines have suffered delays over the last five or more years. When it comes to these maintenance delays, I’ll state the obvious A submarine stuck in a shipyard is not available for combat. We intend to fix that problem.

Next, our boats must be “Outfitted.” This means that all of our boats must receive modern combat systems and sensors so that even our oldest submarines are as combat capable as our newest.

Finally, our ships need to be “Fully loaded.” In simple terms, every tube, every stow, every magazine, needs to be full. This is an additional focus area for us, in addition to submarine maintenance, as we increase the quantity and quality of what we put in our submarine magazines.

So to review this whole illustration, when you look at Readiness from this perspective, a number of key points should emerge. These readiness funding requirements are scalable to our force structure and they are enduring. Our notional readiness cost is about $180 million per boat per year. When we buy future submarines above our current force levels, we have to account for these per boat total ownership costs or our boats won’t be ready in the future. You might be able to take divots out of some of these layers for a year or so to pay for emerging bills, but if you do so over time our ships won’t be ready.

In the past there was the desire to sacrifice readiness investment to pay for new ships and submarines. That’s a false choice; we need them both. We must ensure that our force today is ready and then build from there.

Finally, when we’re talking about Readiness we need to have no confusion. Our ships and our submarines are ready to confront any adversary at any time. These investments are only meant to strengthen our force.

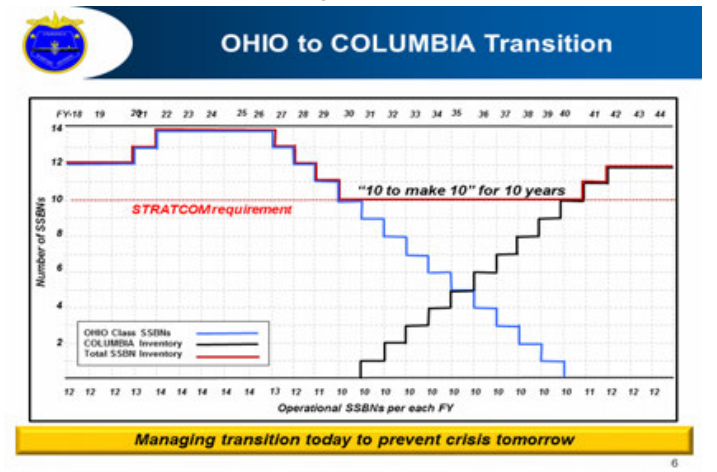

Now that we’ve discussed Readiness, we’ll briefly discuss strategic deterrence. For today’s force our center of gravity is the OHIO Class SSBN and the D5 Trident weapons system. For the future that center will shift to the COLUMBIA SSBN and the Life Extended D5 missile system. Our focus is ensuring we have a seamless transition between today and tomorrow.

In order to ensure this seamless transition, both the submarine and the missile and their associated systems must be maintained and modernized. We’ve already discussed the need to maintain our submarines. For our OHIO class our emphasis is on maintaining or improving each ship’s material condition so it reaches its expected service life of 42 years. Captain Scott Pappano is responsible to make sure that we can achieve that.

As we have no margin for the delivery of the COLUMBIA class, if the ship doesn’t make it, there will be a gap in our operational commitment to United States Strategic Command. As Admiral Tofalo stated, critical to meeting our requirements is keeping our ships at sea by doing efficient and effective maintenance. There are two elements of that maintenance: 27 month refueling overhauls and we have four more ships to complete; and 35 day refit periods in order to maintain the operational availability of our ships at sea.

In addition to the submarine mechanical systems, as we do with all of our submarines, we modernize our SSBN electronic systems to employ the latest cutting edge sensors and systems to outpace our adversaries. We are converting our SSBNs to the SWFTS [Submarine Warfare Federated Tactical Systems] model. Our submarine combat systems that we use on our SSNs; all of our OHIO-class submarines will have SWFTS, and the COLUMBIA will have it built in.

Vice Admiral Benedict just completed a great discussion on the Trident D5, what he has done, and where he is headed. The fact that we can take a D5 missile that was developed in the 1970s and 1980s and extend it through 2084 is an incredible testament to the credibility, reliability and capability of that weapon. We’re all in.

This graph illustrates the biggest future challenge the Navy faces in supporting our mission of Strategic Deterrence. This shows our transition from the OHIO-class to our COLUMBIA-class submarine while continuing to meet our Strategic Deterrent force requirements to United States Strategic Command, which is 10 operational ships.

It shows us completing our OHIO refueling overhauls and then the delivery and certification timeline for COLUMBIA submarines as they come online and the first COLUMBIA goes on its first patrol in October of 2030.

While the COLUMBIA design and construction is front and center,

appropriately in everyone’s mind, we are also working the supporting requirements for manning ashore and assigned to our new SSBNs, our training and ship repair facility infrastructure, and our home porting transition plans. All are part of the puzzle to make sure that we can meet this minimum, non-negotiable requirement. This transition is fully executable. We recognize there are many moving parts that we must get right today in terms of planning and resourcing, and we are, again, fully funded to ensure there is no gap.

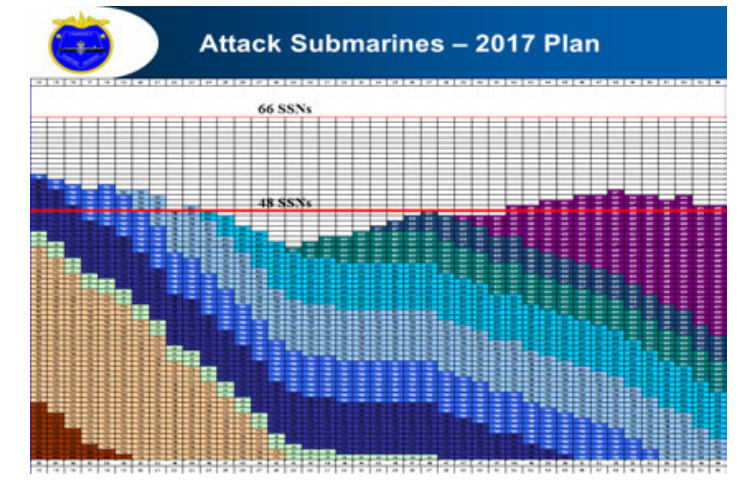

Shifting now to the theater undersea warfare mission, as you know one of our priorities for Undersea Warfare is ensuring we have sufficient forces to meet our Combatant Commander needs, both in peace and war. A key element of those forces is our attack submarine force. For over a decade our force structure objective was 48 attack submarines. In the last year, as part of the Navy’s analysis of the new force structure requirements and given the changing international environment, our new objective is now 66 submarines within the 355 ship Navy.

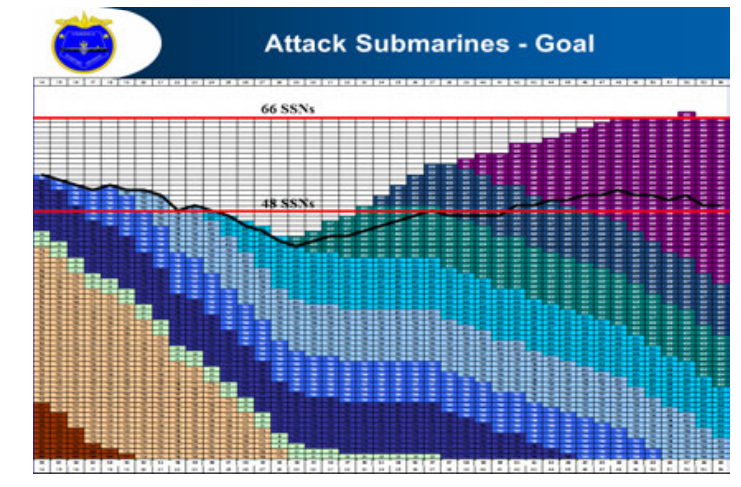

This graph shows you our force structure as projected by the Fiscal Year 2017 shipbuilding plan against a 48 attack submarine requirement. The next illustration shows you what a minimum 2 per year SSN build profile would do to achieve a 66 attack submarine force structure requirement.

This minimum two per year profile gets us to our peacetime and wartime force structure objective and also gives an enduring signal to our industrial base, allows for stable programming and budgeting for our shipbuilding accounts, and gives us a stable assembly line or conveyor belt which allows us to continually improve our attack submarines over time. In line with SECNAV and CNO direction, this notional profile is a minimum foundation from which we will pursue additional measures to achieve our force structure requirement sooner.

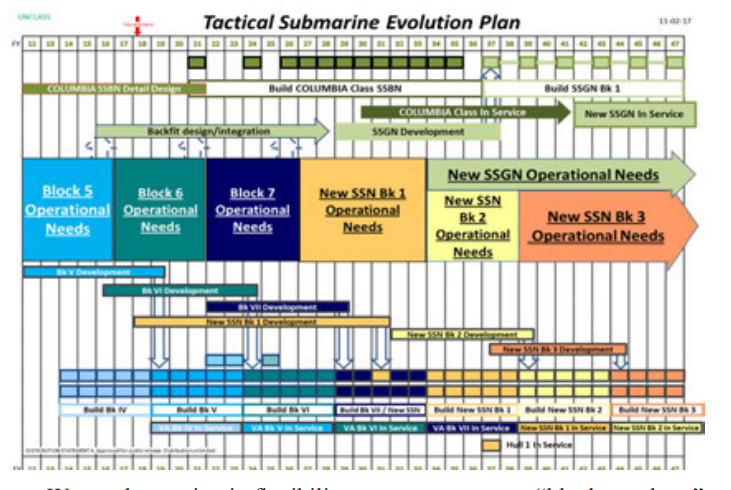

In terms of our attack submarine design, the VIRGINIA-class is a highly capable platform, the best in the world, originally designed for littoral operations, but not necessarily designed for today’s international environment of emerging competition. As a result, the VIRGINIA-class is evolving. Block III introduced the VIRGINIA payload tubes. Block 5 will have the VIRGINIA Payload Module and other additional capabilities.

However, we are running out of design margin in this great platform, and there are some Fleet needs which this platform cannot meet. As a result, under Vice Admiral Merz’ leadership, we’ve started the discussion about how we are going to leverage our block improvement conveyor belt to wring out as much as we can from future blocks of VIRGINIA while setting us up for success after VIRGINIA and COLUMBIA. This effort is what we call the Tactical Submarine Evolution Plan, or “TSEP,” which is our approach to continue to improve our platforms whether on the VIRGINIA or the next generation submarine.

This is a very notional outline of TSEP. We’ve taken a lot of the de- tails out because they’re classified and they need to be, of the capabilities that we are going to demand our shipbuilder inject into this platform. If it can’t be injected into this platform, we’re going to design a new one.

We need to maintain flexibility as we execute our “block purchase” for Economic Order Quantity (EOQ). For instance, Block 5 has a block of five years resulting in 10 boats. The Block 5 starts in FY ’19. If we determine in 2019 we need to incorporate a new capability into that submarine, we shouldn’t wait five years. We need to inject that new capability as soon as possible, so we need to have the opportunity to have mid-block insertions into our platform. Captain Stevens talked about that yesterday.

Our TSEP process also keeps a running tally of these future fleet requested capabilities, which gives us a steady demand signal for technology development to industry and our R&D community. It gives us a ready menu of mature and maturing technology that we will insert when ready. This approach is much like what we do with our SWFTS program and our combat systems, but applied on a much larger, platform level scale.

So we’re now moving beyond the discussion phase into the action phase with submarine force leadership, NAVSEA and the OPNAV staff to execute this plan. We’ll continue to provide details on this effort to our industry partners in the appropriate classified venues.

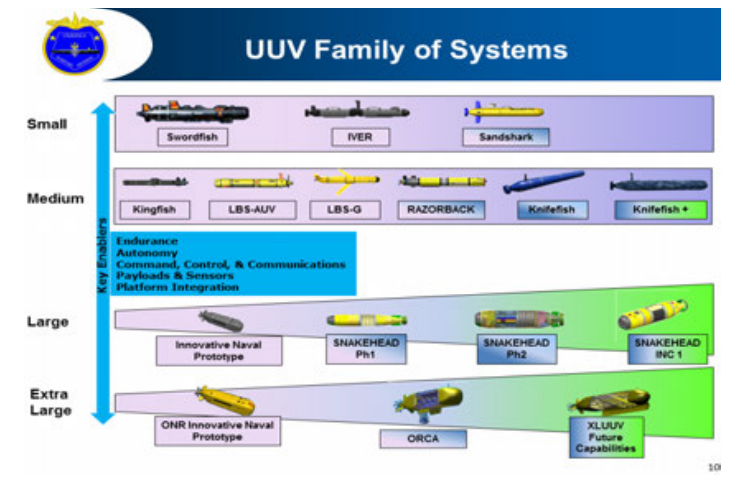

One of our final investment priorities is accelerating delivery of unmanned systems into the Fleet. What you see here is a simple illustration of a UUV family of systems. It follows the framework of the Navy’s report to Congress in February of 2016 titled, “Autonomous Undersea Vehicle Requirements for 2025.”

We divide our vehicles into four classes based on size: Small or Man-Portable; Medium, which are less than 21 inches in diameter; Large, 21 to 84 inches in diameter, which aligns with the dry deck shelter and the VIRGINIA Payload Tube diameter; and Extra-Large vehicles, which are larger than 84 inches. These classes can be employed by a variety of platforms and perform a variety of mission tasks, including environmental sensing, mine warfare, and Far Forward missions where our submarines operate. These vehicles share common technology requirements, including sensors, endurance, autonomy, and command and control.

From this perspective, you can see there is a synergy across the vehicles, mission tasks and technology. Given that synergy, we have consolidated many of these efforts into a single Resource and Requirements Sponsor under N97 and the lead program office, NAVSEA PMS406, and established lead-follow relationships with the other supporting resource sponsors and program offices so we can pool our resources and pool our efforts to get our unmanned systems to the Fleet faster.

When N97, OP- NAV staff, and the acquisition teams briefed the CNO on our unmanned systems vision in his office, he directed that we accelerate all of our unmanned systems in order to deliver to the Fleet as soon as possible. That meeting also provided the direction to consolidate vehicles under N97 to support that effort.

Yes, N95 vehicles are coming to N97, the mine warfare and naval special warfare vehicles. Sydney, you asked a question, what are we doing about working or testing or demonstrating these capabilities? Admiral Tofalo mentioned we stood up UUV Squadron 1 last month. That is the incubator for our Far Forward experimentation and demonstration. They have vehicles today. We’re going to get the vehicles as fast as we can so they can start experimenting, demonstrating, and establishing future requirements in terms of individual vehicles, vehicle to platform, and vehicle-to-vehicle.

There are also other incubators in the EOD community and the special warfare community. We intend to leverage all of them. We are also leveraging industry work, as evidenced by the exhibits on the other floor, what we’re doing with UUVs, as well as our ONR and DARPA partners. So we look forward to providing you updates on our progress at future conferences.

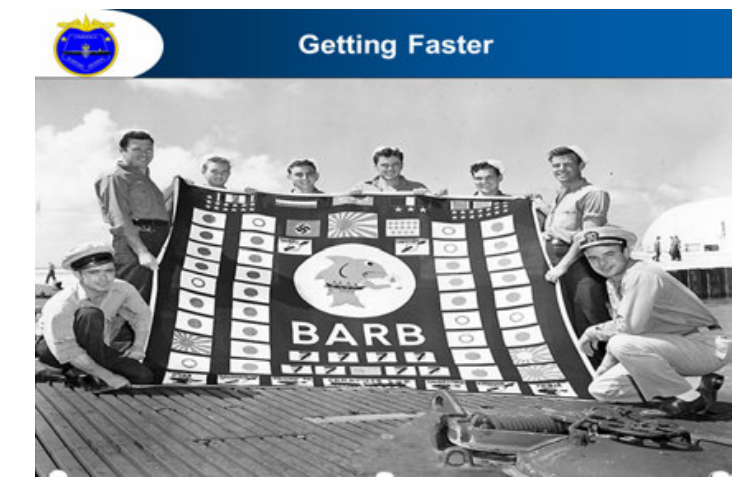

As the theme of this symposium is “Getting Faster,” I want to end my remarks with some perspective on our collective efforts to do just that. In 1945 Commander Gene Fluckey volunteered to install a rocket launcher typically used on amphibious ships for shore bombardment on his submarine, USS Barb, while in a shipyard period in Mare Island Naval Shipyard. On his next war patrol he launched 68 rockets, bombarding the Japanese mainland. From this innovative request, to putting ordnance on target, was a span of less than four months.

In 1955 the Chief of Naval Operations, Arleigh Burke, directed the Navy to pursue launching a ballistic missile from a nuclear submarine, the first of which, USS Nautilus, had just gone to sea. In 1960 USS George Washington launched the first submarine launched ballistic missile, five years from concept to launch, including just 14 months to modify the submarine to add a missile compartment.

Fast forward to the 1990s and we were challenged by Submarine Force leadership to regain our acoustic advantage by leveraging the commercial computer industry. Acoustic Rapid COTS (Commercial-off- the-Shelf) Insertion (ARCI) was born, informed by experimentation and demonstration, and software insertion continues. That pace of rapid technology and software insertion continues to this day.

Fast forward again and we see the rapid demonstration of unmanned air and unmanned undersea vehicles from submarines, from concept to demonstration in years, not decades. Again, these vehicles are now formal programs. Admiral Tofalo’s Undersea Rapid Capabilities Initiative is the engine driving undersea innovation today, and we at N97 fully support those efforts.

This brings us back to Barb. Four months from concept to combat. We cannot be that fast today, but we need to. While we have examples of going faster and fostering innovation, we aren’t going fast enough or far enough. The CNO continues to challenge us to get faster. Our competition is catching up, and that’s unacceptable. We have to break free from our comfort zone and go faster with our major programs through accelerated acquisition efforts, through developing new payloads, systems and sensors, and through rapid prototyping and demonstration efforts.

Before the meeting this morning I had a discussion with a friend from industry. He said, “what should be some of those examples and what should we be mutually confronting?” As a start, I’d say contracting, test and evaluation cumbersome requirements, taking risks in prototyping and demonstration, putting things on submarines faster, like Tom Nutter used to do with his famous “Nutter Clutter.” We need to be able to embrace that risk and get them on our ships faster, and then accelerate those into Programs of Record.

We talked about the CNO’s charge to us for UUVs. We are finding and flattening every impediment for the acceleration of our UUVs into the fleet, many of which were on that list I just talked about, and reporting those efforts to the CNO for his assistance when required. To go faster takes changes in how we design, how we contract and what risks we accept. On the Navy Staff we are challenging the status quo and pushing to meet the CNO’s challenge and support our future “Gene Fluckeys” and the crew of the next USS Barb.

Finally, I’ll leave you with a few closing points from the Undersea Warfare perspective. First, we are committed to strengthening our Fleet’s readiness. Second, we are fully committed to our Strategic Deterrence responsibilities from cradle to grave. We are focused on sustaining and improving the most lethal undersea conventional force on this planet.

In this period of renewed political competition, we must go faster to stay ahead in order to strengthen deterrence and ensure victory. We will do so by removing impediments to innovation and incentivizing cost re- ductions in our programs so we can reinvest those savings to buy more lethality. Finally, we cannot buy the Navy the nation needs through internal reform alone. We need relief from the Budget Control Act.

Thank you, again, to the Naval Submarine League for your continued support for our Navy and our Submarine Force and the opportunity to address this symposium. I welcome your questions.