Thank you very much. I greatly appreciate the opportunity to address you today. What I’m going to do is walk through three sections of

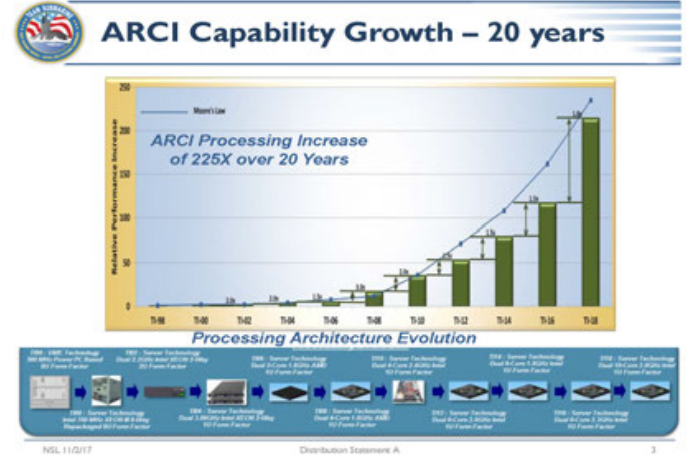

I’m going to start with acoustic rapid COTS insertion. The reason I’m doing this is partly to recognize that yesterday was an important date, because on November 1, 1997, 20 years ago yesterday, we delivered the first ship set of ARCI equipment and installed it on USS Augusta (SSN-710). Of course, neither that equipment nor the Augusta are with us anymore, sadly, but it really started a revolution in the way we provide combat system electronics.

The first ship set was a single work station, a single processor, single server, and it provided towed array processing for the TB-23 thin line array. Phase two added a second work station and the ability for dual array processing, both the fat line and the thin line, TB-16 and then TB- 23 and then later the TB-29.

Phase two also brought in the hull arrays. Phase three brought in the spherical array, and phase four brought in the high frequency sail array. All of that commercial off the shelf electronics equipment to process existing arrays.

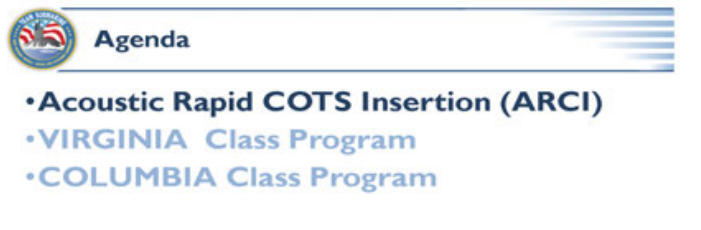

After that, we moved on to the TI-APB process and that really has been foundational to the success of our submarine force over the last 20 years in reaping the benefit of the tremendous advances in electronics. This graph shows the curve of Moore’s law, and the green bars show the processing increase over the last 20 years. From the early days of ARCI to today, we have increased processing capability over 225 times. So, 225 times the capability that we had 20 years ago.

This slide shows hardware. It shows processing capability and it shows the print is pretty small but along the bottom line it shows processor speed and server space. What took us eight units of rack space in the early days is now less than one unit, and the processing, again, is 225 times what it was originally. At the same time, we have developed software increases.

We do have very detailed metrics that we use to analyze the benefit of the software we provide in solving the fire control solution. It’s not only “is the processing good enough,” but are the algorithms, the human machine interface, the displays, the functionality, and the ability for a sailor who has been through a fairly limited amount of training, to sit down and quickly adapt himself or herself to the system that they’re using and generate the desired results? The way we do that is classified, but it deals with things like if there is a threat contact out there, can you detect it? Can you discern it from the information displayed on your sonar screen?

If you are holding a contact, can you develop a fire control solution and how accurate is it? If you have a contact, how long can you hold that contact? All of that is a function of not only the training of the operators, but the ability and capability that we provide to help the operator do their job

And during this process we’ve also taken advantage of the unique aspects of electronic systems, in that the cost comes down as the capability goes up. That chart on the lower right, ship set cost is in then-year dollars. So not even adjusted for inflation, and we’ve had absolutely real cost drops for more capable equipment over the years.

In fact, electronics is the one area where you should never award a firm fixed price contract, because if you do over a period of time you will miss out on cost savings. In recognition of the 20th anniversary of ARCI being yesterday, I wanted to give you a sense of how far we have come in those 20 years.

Let’s move on to the Virginia-class program. The Virginia-class program is in great shape.

We are absolutely at two per year delivery. Jay Donnelly was saying, in my four years as program manager I delivered four submarines. That is below the standard now. A four year program manager will be expected to deliver eight submarines from now on, and he will.

Two per year delivery cadence, one each out of Electric Boat and Newport News, at the current pace. In doing so, we have significantly reduced the contracted build span for each of the submarines and significantly reduced the amount of time that it takes to turn the ship over to the fleet. Admiral Johnson mentioned that on the slide, and I’ll talk a little bit more about it.

Fifteen submarines delivered to date, 11 more under construction, two more after that under contract that will start over the next year. Since the last time I addressed this group, we approved an extension to the acquisition program baseline, or APB, that took us from a 30-ship class which was the original intent of Virginia, to 48 ships. By the current shipbuilding program of record, that will take us through fiscal year ’33, however I expect that we’ll hit 48 total well before that. Then we’ll make the decision, do we extend the APB again or will it be time to move on to a future submarine design?

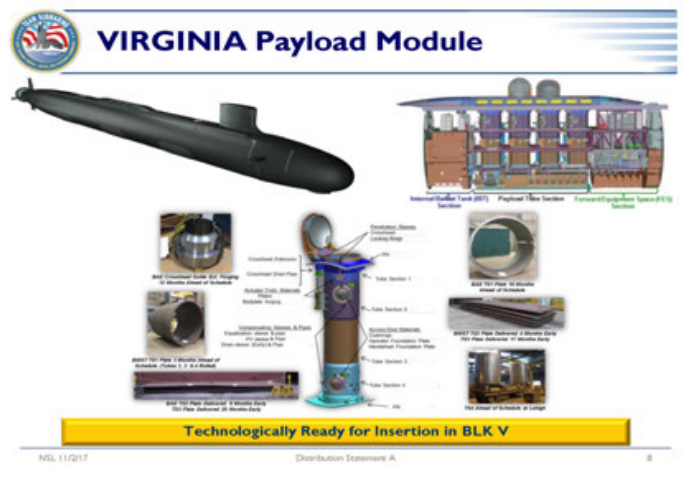

The Virginia Payload Module is progressing well. We are technologically ready to install that on the second ship in the block 5 contract, the second ship of fiscal year ’19. Block 5 will be a 10-ship contract from fiscal years ’19 through ’23. We’ll build two of the submarines every year.

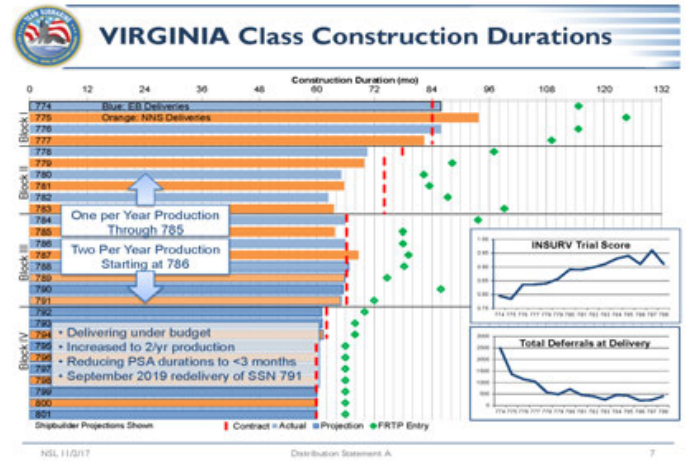

This is the chart that Admiral Johnson showed. The way you look at this chart, the blue lines are Electric Boat and the orange lines are Newport News. The green diamond is when the boat is redelivered out of post-shakedown availability and we actually turn the keys over to the type commander for him to train and provide that as a deployable asset to the combatant commanders.

There are two things that you want to look at here. The original contract span of 84 months has been reduced down to 60 months for the last eight ships of the block 4 contract. That is a two-year reduction, from seven years to five years, in our agreement with the shipbuilders on how long it is going to take to build these submarines.

The green diamonds, from the very early days, our longest one way out here to the current green diamonds and projected green diamonds, is a four year reduction in how long it takes to deliver the ship, get it back into PSA and out of PSA and to the type commander.

That’s a tremendous improvement in how quickly we can get these boats into their hands. That’s critically important. As I’ll show you in a minute, we still have a trough that we’re facing, and one of the ways to mitigate the impacts of that trough is to get the boats to the fleet faster.

The task that I have set for Captain Mike Stevens, which he has agreed to execute, is that on these boats, starting with this one which is the 791, the Delaware, the last ship of block 3, the goal is to deliver the ship and then within six months complete PSA. We’re aiming for a three month post delivery testing period where we do acoustic trials, weapons system accuracy tests, and then bring her back in for a three month PSA and get it to the type commander in six months. The reason we can do that is because of these two trends.

Quality of delivery, the top graph is the INSURV trial score. Our last six boats have all been above 0.9. The bottom one is total deferrals at delivery. What are the things that we couldn’t finish that we recognize were not important enough to hold up the ship from being delivered, so we process a waiver or deferral request (WDR) and defer it to PSA. You can see a tremendous advance in reducing those numbers, which goes into the work scope at PSA. So, the fewer WDRs we have, the less work there is to do in PSA and the more confident we are that we can turn that boat around back to the fleet in less than six months.

Virginia Payload Module, this is quickly becoming a reality. The Virginia payload tube is a similar design to the Columbia missile tube with some very key differences. Both the Columbia missile tube and the Virginia payload tube have an integrated tube and hull assembly at the top where it fits into the ship’s hull. The Virginia payload tube also has an integrated tube and keel assembly, as opposed to the missile tube on Columbia, which is just the end of a cylinder welded to the hull.

So many similar things, and that led us to the effort of continuous production of missile tubes. We took a holistic view and said, for all of the tubes we’re building for the Columbia class, plus all of the tubes that the UK is building for the Dreadnought class, plus all of the tubes on Virginia, both the payload tubes in the bow and the four payload tubes in the Virginia Payload Module, we have to figure out a way for the shipbuilders to do this smartly, efficiently and with savings.

We did that through continuous production under specific legislative authority from Congress. We have pulled work to the left to more smoothly ramp up the requirement for the vendors that provide the components for the tubes with the key producers, BWXT, BAE Systems, Babcock Marine and Northrop Grumman, through their subcontractor PCC, actually producing the tubes and then sending them to Electric Boat and Newport News for them to be outfitted and installed in ships.

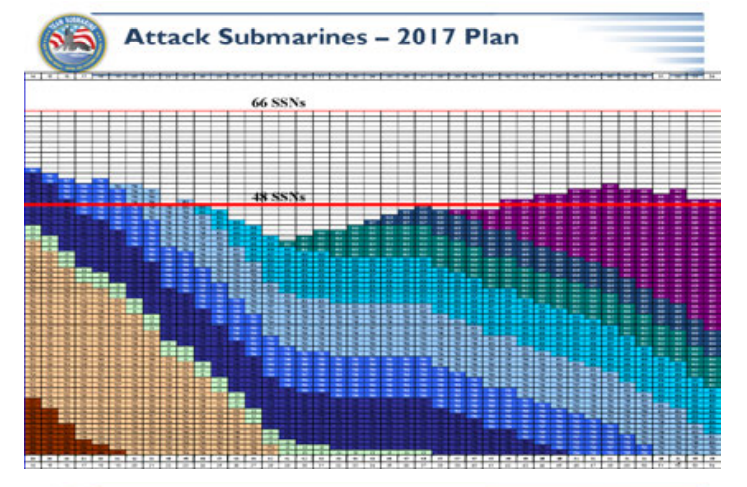

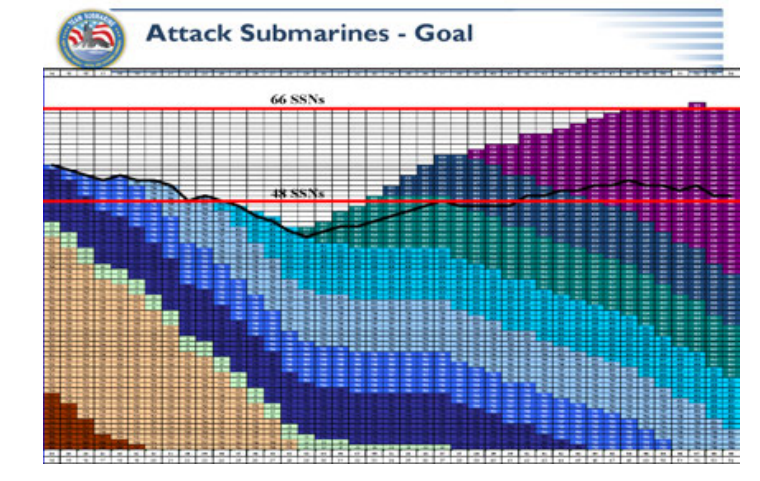

I showed you this last year, and this is what we call the chicklet chart. The 48 SSN requirement, that’s old news. Under the force structure assessment released in December of last year, the attack submarine requirement is now 66 SSNS. So, we used to talk about this trough, now we’re talking about this trough.

Obviously, you can’t snap your fingers and make that go away. But, what we can do is recognize that, as Admiral Johnson said, if you want 66 submarines and they last for 33 years each, then you have to build two every year forever to reach and maintain 66 attack submarines. So, in the

current plan, if you build two submarines every year you get this profile, and then you reach 66 submarines in about 2048. Again, that’s a long way away. But the other thing you have to realize is that while you’re building two submarines remember the trough that we used to look at is where this black line goes under the red line, you’ve now greatly reduced that. And for every second submarine you build instead of one, that’s another submarine that you have in the inventory during the critical coming decades. So you’re chipping away at it.

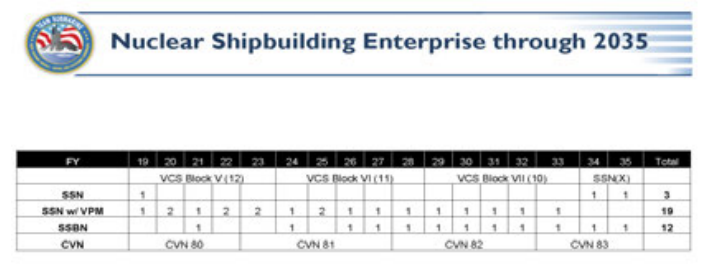

This represents the combined enterprise work: attack submarines, and I split it out into attack submarines and attack submarines with VPM; ballistic missile submarines, which is Columbia class; and aircraft carriers, which is the Ford. Right now the program of record, because we haven’t published a new shipbuilding plan, has this one-two, one-two cadence with one attack submarine every year where we’re building a Columbia.

In testimony earlier this year with the rollout of the Navy’s ’18 budget, Acting Secretary of the Navy Stackley committed to changing this one to a two. So you can look at that and say okay, the second submarine in FY21 is going to happen. We’re already programming for it in the

FYDP. We’ll get advanced procurement two years early in FY 19. As I said, we’re already entering into initial discussions with the shipbuilders on a block 5 contract for at least 10 submarines.

But, there are all these other ones beyond that. So the question becomes, what kind of commitment can we give to the shipbuilders and to the suppliers and vendors that make up the industrial base on submarine construction pace? Because our Congress appropriates money on a one-year basis, and because the Navy and the Department of Defense program for money on a five-year basis, we really don’t know what’s programmable beyond FY22 right now, because that’s the FY18 FYDP which is in play.

Now of course the POM19 FYDP is almost done and POM20 has already started, so we do know what’s going to go on. I can tell you that there will be an incredibly strong effort by the Navy everywhere you see a one here to change that to a two. You heard Admiral Johnson say it earlier today, we’re going to build two per year forever.

We have to in order to provide the requirements the force needs, the 66 attack submarines. We’ve been working very closely with the shipbuilders on ensuring that we understand exactly what has to happen for us to be able to build two Virginias with VPM and one Columbia in the same year, while we’re of course building aircraft carriers down at the bottom.

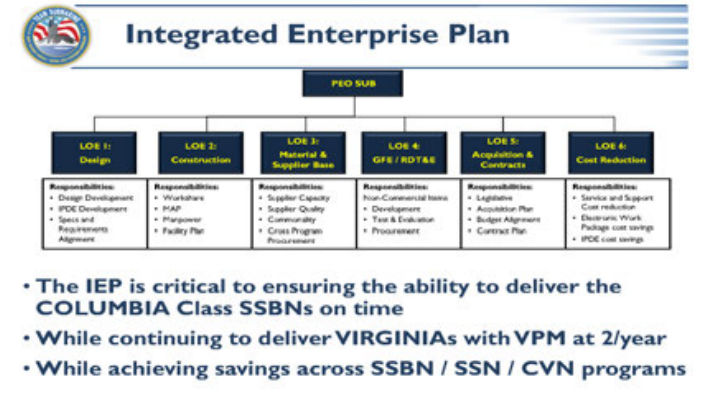

So how do we do that? Well, the answer is the Integrated Enterprise Plan. Admiral Johnson referred to it. I’m going to refresh your memory. I showed you a version of this last year.

The key is we have defined six lines of effort and put teams together between PEO Subs, both the Virginia program and the Columbia program, PEO Carriers and the nuclear shipbuilders, Electric Boat and Newport News. They are focused on the design, LOE-1. This includes the design tool, Integrated Product Development Environment, which is a new tool that we have fielded for the design of Columbia.

We’re also using it to design the Virginia Payload Module. It is well beyond the previous tool we used, Catia, but it is a process to get it fully fielded, all the bugs worked out and performing like it needs to be. We are doing well at that. We will continue to work on it and it will provide us the capability we need to design.

The other part that that tool does is not only the technical authority, but how you go build the submarine or the aircraft carrier. There are a lot of advances being made by both companies, Newport News with the integrated digital shipbuilding. This is, instead of walking down to the shop or to the graving dock with a stack of paper to tell you how to weld a hanger to a bulkhead or the hull, it’s walking down with an iPad.

That provides a tremendous advantage in terms of augmented reality. You can just hold up the iPad and it focuses on targets that are set into the system and shows you exactly where it has to go, rather than trying to take measurements off of a drawing. It is more user friendly and it’s a system that the young employees coming into the yards today find more familiar with what they’re used to from already growing up in the digital age.

Line of effort two, construction. This is mapping out the build plan. How you build two different submarines and an aircraft carrier in common facilities across the shipbuilding yard, and really nailing down through the manufacturing and assembly plan how the components move through the yards.

Line of effort three, this is one that gives me probably the most headaches because line of effort three focuses on the material procurement side from the suppliers and vendors that make up the submarine industrial base, and also those that contribute to the aircraft carriers as well.

The workload that is ramping up in the coming decade is so significant, beyond what we have seen since the very height of the Cold War, that we are out there every day assessing individual suppliers and making sure that they have the capacity and the quality to meet the requirements for the programs.

If they do so, then the next step is how can we combine purchases with the suppliers, from the prime contractors, across these three programs such that the Navy reaps the benefits of increased economic order quantity? That’s a tough process, because it really requires managing that supplier base strategically instead of on a transactional basis.

Line of effort four is government focused. There’s a lot of government furnished equipment that goes into the submarine and the carriers, things like propulsor, the non propulsion electronic systems, which is ARCI, TI-APB, submarine warfare federated tactical systems, SWFTS, and then also the component development.

Line of effort five is acquisition and contracts, working very closely with Congress to get the legislative authority that we need to do things like missile tube continuous production, which I talked about.

Finally, line of effort six. Line of effort six is cost reduction, making sure that these boats remain affordable and doing everything we can to reduce the cost such that the burden on the rest of the shipbuilding that the Navy needs to do is not outweighed by submarine construction. This Integrated Enterprise Plan is critical to the success of both the Virginia and the Columbia program, and also the aircraft carriers for common material.

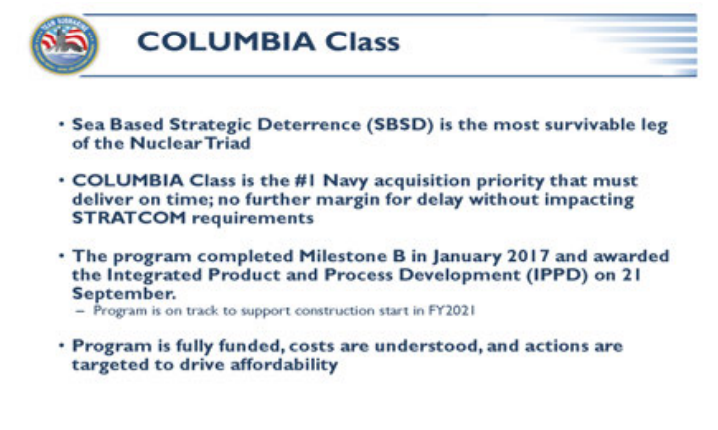

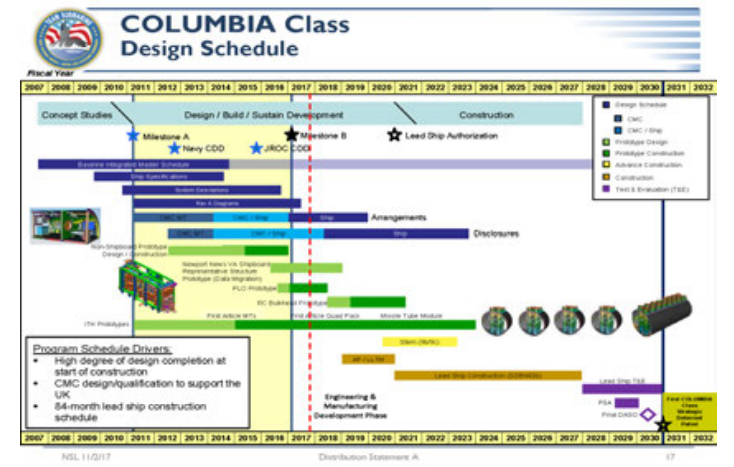

Let’s move on to the Columbia program. Again, a very good year. Since I addressed you the last time the biggest thing is that we successfully achieved Milestone B. We went before a Defense Acquisition Board in November of 2016 and then USD AT&L Frank Kendall signed the milestone decision authority memo in January 2017 in what was probably one of his last official acts before administration turnover. We have achieved the transition to the EMD phase, engineering and manufacturing development.

The other big thing was in September, so a little over a month ago, we awarded the integrated product and process development contract to Electric Boat to complete the design of the Columbia. We were operating under an R&D contract for early design. This now moves us into the detailed design and construction readiness phase and sets us up for

completing the design and then starting to order long lead time material and then starting construction on the first boat in 2019.

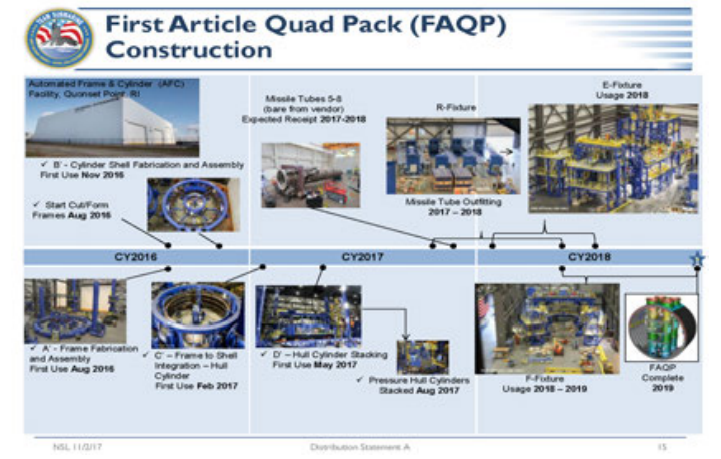

So, although our official construction start is 2021, we’re actually going to start using advanced procurement and advanced construction authority that has been in legislation since 2016 to start construction in 2019 on key early components. However, in reality, we have already been in construction for over a year because we had arranged for special R&D funding for several prototype efforts. The biggest prototype effort is the first article quad pack construction.

A little on how to build a submarine 101, it’s through a series of fixtures, and the A fixture marries webs and frames in the cylindrical basis, and so you end up with one web and frame, circular, coming out of the A fixture. It then goes to the B fixture where the shell plating is rolled and assembled using a very close tolerance circularity requirement. Then in the C fixture that shell comes down and you marry the web and frame from the A fixture goes inside the shell and is welded into place there.

A set of web and frames from the A fixture go in there and make up the full half cylinder, and then two deliverables from the C fixture go into the D fixture and get stacked together. That becomes your first hull cylinder. That is just for a normal hull cylinder. For what we’re doing in the

automated frame and cylinder facility for Columbia in Quonset Point, is then marrying that with work on the missile tubes coming in and getting outfitted on the R fixture. Then they go into the E fixture where they are paired together, four tubes into a quad pack, and then they go into the F fixture and those four tubes get married with the hull cylinder that came through A, B, C and D to form the first article quad pack.

This is a time lapse video that shows you some of what I was de- scribing. It’s not in sequence the way that I did, because of the vagaries of shipbuilding. Over the time that they were doing this video, it just doesn’t line up to go A, B, C, D, E and F.

The next thing, the first missile tube, has already arrived. The second missile tube is supposed to arrive today. (Editor’s Note: Someone in the audience said that it did arrive.) It did. That’s really good because it was stuck at the border of Rhode Island for quite a while, while they worked out road permits and finishing construction on road repairs, so they could actually get into the state. So the second missile tube has arrived. They both go on the R fixtures and will have piping packages outfitted onto them.

So this process is critical to the ability to build the ship in seven years. It is fundamentally different from the way we did it on Ohio. By starting it now, prototyping it early and working all the bugs out, it will provide significant benefits down the road.

Other prototypes that are in progress right now, we already finished the non-shipboard prototype. We’re prototyping two efforts in partnership with Naval Reactors, the propulsion lube oil system prototype and the reactor compartment bulkhead. This prototype, commonly known as the birdcage, is a Virginia section that we’re using to transmit data from Electric Boat down to Newport News to ensure that everything talks to each other and they get a workable product in Newport News.

As I said, the biggest one of all, first article quad pack, we’ll make four of those and produce the first missile tube module for the first ship, all under R&D funding as a prototype.

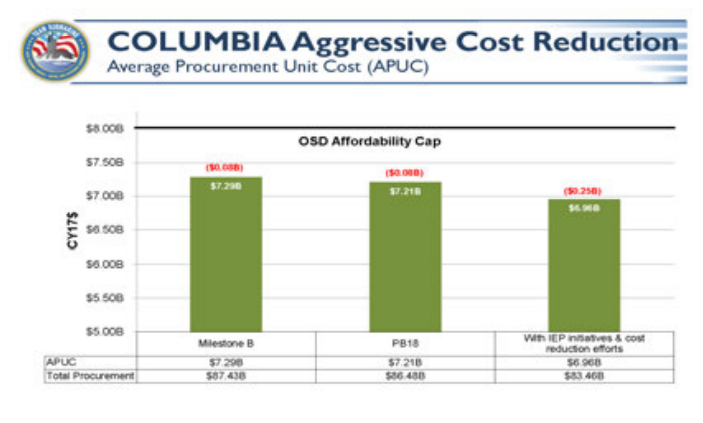

The last thing I want to talk about is cost. As I mentioned a couple of times already, we’re sensitive to how much this program costs and we’re working on it aggressively to ensure that we always remain underneath the affordability cap and that we’re doing everything we can

to further reduce cost. At the Milestone B our average procurement unit cost, APUC, was defined as $7.3 billion. That is the average cost across all 12 ships in CY17 dollars.

The affordability cap was assigned at $8 billion, which is 110 percent of $7.3 billion. In the first year since the Milestone B was achieved, through innovative legislative authority and contracting techniques, we’ve already reduced costs by $80 million per hull to bring APUC down to $7.21 (billion).

That was a combination of missile tube continuous production, which I talked about, and advance construction, which is pulling key construction activities to the left. Really the focus of that was to reduce the risk of not delivering on time, but it had an added benefit of savings as well. So those two efforts, advanced construction and continuous production of missile tubes, resulted in a new APUC of $7.21 (billion).

Within the IPPD contract that I discussed we awarded a little over a month ago, there’s also a significant cost reduction incentive for the lead ship. So we are incentivizing the shipbuilders to do everything they can to continue refining the design and the producibility methods within their yards to reduce the cost of the lead ship, and then of course the ships that

follow after that. But the incentive is measured on the lead ship, so if we’re successful in that, and if we’re successful in some of the additional legislative authorities we’re pursuing, and funding that we’re working with the Navy to provide, such as continuous production of other things besides the missile tube, then we have the ability to get APUC below $7 billion. That is a stretch goal, but again as I’ve said, when you understand that the cost of this program is significant, then we really need to do everything we can to buy margin back into the program, both in terms of cost and schedule.

With that, a quick tour around recognition of ARCI’s 20th anniversary, Virginia program, the Columbia program and the Integrated Enterprise Plan, I’ll be happy to take a couple of questions.